(ST. LOUIS) – I grew up a Catholic and a feminist, a member of two groups preoccupied by abortion. You’d think I’d know a great deal about the procedure. But as I entered my childbearing years and friends started confiding details of pregnancy, fertility struggles, miscarriages, and abortions, I realized my knowledge about reproductive health and abortion was outdated. And I wasn’t alone. For years, advocates on both sides of the abortion issue have sometimes used graphic imagery to influence the political or legal arguments, even as abortion itself has changed fundamentally. Now that the U.S. Supreme Court has said states can ban abortion, what do Americans need to know?

Although 80% of the public think abortion should be legal in “some” cases, “the truth is that many Americans just don’t like talking or thinking about abortion,” Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux says in her reporting on polls of Americans’ views about abortion for Five-Thirty-Eight.

Rebecca Traister, a writer for New York Magazine and author of several bestselling books, calls the reluctance to discuss abortion, even by those who support it, “the ick factor.” It seems hesitancy in talking about abortion has contributed to widespread cultural misconceptions about it.

Since the June 24 Supreme Court opinion overturning Roe v. Wade, over a dozen states with trigger bans have changed the rules on abortion access or will do so in a matter of days or months, according to Politico. Others may follow. After five decades of settled law, whether and how to limit abortion is at issue again for large swaths of the population as states sort it out legislatively. While our society reconsiders these questions, we must recognize the disconnect between what people think abortion entails and the reality. We can’t let the ick stop us from knowing precisely what we are talking about.

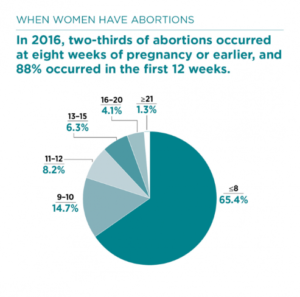

In 2020, a poll showed that 69% of those asked incorrectly believed that most abortions occur eight weeks or later into pregnancy, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Actually, 65% of abortions occur in the first eight weeks of pregnancy, approximately 90% of them by 12 weeks, and 98.7% by the end of 20 weeks, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

65% of abortions in the U.S. occur in the first eight weeks, and 98.7% by the end of 20 weeks, according to the Guttmacher Institute. [Credit: Guttmacher Institute]

Though many people have heard of Plan B emergency contraception, also known as the “morning-after” pill, there’s confusion between this and “medication abortion,” a combination of drugs — mifepristone and misoprostol — prescribed for termination of early pregnancy. These medications, sometimes called “abortion pills,” can be taken up to 11 weeks into a confirmed pregnancy and can be self-administered under a doctor’s advice in the comfort of one’s home, ending the pregnancy with manageable cramping and bleeding, similar to a heavy period. Many who have partial miscarriages and need to evacuate the remains of the fetus from their bodies use the medications.

Today, 54% of abortions in America are induced with these two medicines, according to the Guttmacher Institute. Although this type of abortion is becoming the norm, 79% of Americans have never heard of medication abortion, according to Kaiser Family Foundation.

The truth is a growing majority of abortions in the U.S. cannot be practically distinguished from a natural miscarriage.

Though it’s not often discussed, the experience of early miscarriage is incredibly common for those of childbearing age. According to the National Institutes of Health, 26% of all pregnancies and 10% of clinically recognized pregnancies end in miscarriage. Some suffer tremendously from chronic miscarriage, late miscarriage, and stillborn births — that’s not what I’m talking about here. In most cases, miscarriage happens early in pregnancy. Some research even suggests that most human pregnancies end in miscarriage.

Test your own knowledge about abortion and reproductive health with this New York Times quiz.

Gruesome Images

The fact that many Americans have a gap in knowledge about abortion procedures may be due to cultural squeamishness in discussing women’s and non-binary bodies and health. But those against abortion have often filled the empty space with repellent images of dismembered fetuses and bloody fetal tissue on placards outside clinics. Protesters use the same images, typically of late-term fetuses, over and over. Because gaining access to operating rooms isn’t common in the U.S., the photos are likely from overseas, according to Slate.

Using graphic imagery to influence public health policy is a common strategy. The “meth mouth” campaign in the early 2000s featured photos of people with rotted and missing teeth supposedly caused by using methamphetamine. The ads were meant to scare people from using the drug. Scientists later published a report that “meth-related physical characteristics such as rotten teeth, thinning hair, and bad complexions…are more likely related to poor sleep habits, poor dental hygiene, poor nutrition, and dietary practices” than to the drug itself, according to an article in Reason.com.

Earlier this year, the University of North Carolina published a study in which photos of necrotic diabetic feet and fat-encased hearts were placed on the labels of sugary drinks to fight obesity. The lurid pictures were intended to sway people from buying the beverages and led to a 17% decrease in purchases. Disgust, it turns out, is a powerful motivator.

But gruesome imagery is stigmatizing to patients, health conditions, and treatments. If patients were forced to look at a photo of a surgeon sawing through a chest cavity on their way into a bypass or at their bloated, putrescent appendix after having it removed, we’d call it cruel and a danger to public health.

At times, both sides have used inaccurate or outdated imagery. Even some supporting abortion, like the famous portrayal of a back-alley abortion in the movie “Dirty Dancing” or the coat hanger symbol hearkening back to the darkest times, raise the cortisol. They are a far cry from the safety and ease of current procedures offered by medical advances.

“In terms of our cultural imaginary, those stories are important,” says Maya Gurantz, artist, writer, and co-host of The Sauce Podcast. “But those stories blot out the much more common story of abortion as something that happens early and is usually uncomplicated,” she tells The Click.

Abortion in the Real World

To correct misconceptions about abortion, researchers Steph Herold MPH and Dr. Gretchen Sisson of the ANSIRH program at Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health study how it’s portrayed in the media. They spend much of their time looking at how stories of abortion onscreen match up to real life.

“They pretty much couldn’t be more different,” Herold tells The Click.

On television, the majority of characters who have abortions are young, white, not parents, and middle class or wealthy. In reality, most people who have abortions are over 20, women of color, already raising kids, and struggling to make ends meet, according to their research. She also points out that most onscreen abortions happen at a clinic, which isn’t the case in real life when many happen at home and a not-insignificant number happen at hospitals.

Slide the center divider left and right to compare anti-abortion signs [Credit: Shutterstock] with Glenna Gordon’s photo of the more common abortion result: six to eight week fetal tissue [Credit: Glenna Gordon]

Photojournalist Glenna Gordon also wanted to set the record straight about abortion. She tells The Click that she aimed to photograph a more nuanced version of abortion in America as a response to the gruesome photos. Her groundbreaking images, like this photo of abortion tissue at 6-8 weeks when most abortions occur, were published in the Guardian and Buzzfeed.

The Problem with the Word’ Choice’

Apart from images, some reproductive justice advocates consider how words may reinforce the ick factor, communicating that abortion is shameful or disgusting. Many now encourage the embrace of the word abortion rather than the equivocal-sounding phrase “pro-choice.”

In 2013, Planned Parenthood announced that they would no longer be using the term “pro-choice,” according to the New York Times. The organization recognized the term’s poor framing and failure to put it in context within the lifelong continuum of reproductive health.

“If you look at the way that “choice” occurs in common speech within the United States, it tends to co-occur with consumer things,” political consultant Anet Shenker-Osorio told Slate’s Mary Harris on the What’s Next podcast. “We tend to use the word choice in situations in which we’re making inconsequential decisions without much deliberate thought,” she said.

Rebecca Cohen, graphic artist, creator of the comic GynoStar, and co-host of The Sauce podcast agrees, telling The Click the word “suggests some type of implied superficiality” or “frivolity.” When “choice” goes up against the gravitas of the word “life,” it’s bound to lose.

“I think ‘choice’ is garbage language,” Traister tells The Click by email.

Traister says euphemisms for abortion bolster the notion that there is something particularly off-putting about abortion and “erase the ways in which all kinds of other policies — access to healthcare, affordable housing, paid leave and childcare, access to public transportation, jobs and a more just criminal justice system are absolutely key to make choices about whether, when and under what circumstances to have a child.”

She says the reproductive justice movement should instead use language that lays claim to the moral stakes of the issue. To her, abortion conjures words like “familial flourishing, economic security, and freedom,” as she told Vanity Fair’s Joe Hagan.

The Need for Authentic Representation

How would more accurate portrayals and symbols of modern abortion look?

An alternative image of abortion might look like this. [Credit: Shutterstock]

Maybe the symbol for abortion today should be a half-filled glass of water on a coffee table, sitting next to a pair of small white pills. Or a patient propped up on the couch at home with a heating pad, like the men who disproportionately seek vasectomies before March Madness so that they can watch the games while they heal. Or a family with older children, choosing to forgo an infant they can’t properly raise.

For generations, those dealing with pregnancy have often shared the details about abortion and reproductive health in whispers among themselves. “Pro-choice” politicians have supposedly supported abortion while rarely uttering the word. As our communities consider potential changes in state abortion laws after 50 years, it will be essential to shrug off the ick and bring reality into the light of day. It’s time to start talking about abortion in direct and simple ways, rather than how we have vaguely imagined it.