(Fort Lauderdale, FL) – Outside of covering a warzone, uncovering corruption through undercover reporting is quite possibly the most dangerous journalism work a reporter can do. Working in both areas can result in the same thing — violent death.

That’s why the work that Anas Aremeyaw Anas and his team did to uncover corruption at the highest levels of Ghanian football was so extraordinary. But that work did not come without cost and consequences that continue to this day.

Background

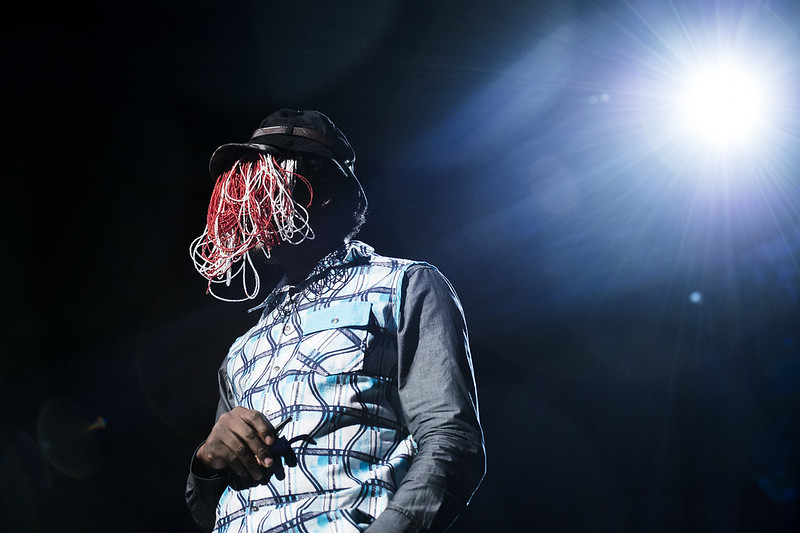

Ahead of the 2018 World Cup in Russia, Anas and his investigative team decided to do an undercover investigation into corruption in Ghanaian soccer. Anas is one of Africa’s most famous investigative journalists, and his trademark is that very few people know what he actually looks like. He hides his face behind a veil when doing interviews and appearing in public to protect his present and future undercover work and his personal safety.

Prior to his investigation into soccer, Anas investigated the judiciary in Ghana in 2015. He and his team managed to catch more than 100 officials taking bribes on hidden cameras in return for influencing court judgments. His work resulted in the removal of 13 high court judges, 20 lower court judges, and 19 judiciary officials.

Now, in turning his attention to soccer, he knew that corruption in the sport overall is nothing new. FIFA, soccer’s world governing body, has had numerous scandals related to international tournaments, money laundering, and World Cup bids — including for this year’s 2022 World Cup in Qatar. But when caught, FIFA and others have simply condemned the corruption publicly, banned the main characters involved, and then quietly devised better ways of hiding it.

The same cannot be said for Ghanaian football.

With a lucrative league structure in place and a national team competing at the top levels on the continental and world stage — which resulted in payouts from FIFA and the Confederation of African Football, or CAF — that money was never seemingly put back into the game. Unlike in other countries, there were never any new facilities built, and no grassroots development took place. So Anas and his team asked themselves, why not? Is there just not as much money in the system as people think? The answer they got back was that there is plenty of money — it’s just going to the wrong people.

The investigative team started small by targeting officials who worked on games at the national league level — for a comparison, think MLB or NFL here in North America. League referees are paid US$170 per game, so Anas and his team offered just a bit more. They told officials they were part of a fan group for one of the teams, Hearts of Oak, and were offering them “gifts” for officiating their games, hoping that when the time came, the officials could “help” their team to get a good result. Then, via hidden body cameras, Anas and his team recorded 20 officials happily taking money and saying they’d do what they could to help.

Eventually, they set their sights a bit higher — on the man who assigns the officials to club games — hoping they could get the officials they had already bribed assigned to more of their club’s games. It didn’t take long before they also had this “fixer” on camera taking GH¢2,000 cedis (US$245). Not only that, but he also set them up with two other officiating committee members who were also filmed taking money, including one who trains officials in 16 other African countries.

The team then expanded their undercover work to see if they could influence officials outside Ghana. They quickly recorded four international officials taking US$700 each — among them, one of the top referees in Africa. From there, they were offered help by their previously corralled “fixer,” who made introductions that allowed them access to one particular referee who was set to be part of the officiating team at the 2018 World Cup. He was also recorded accepting a “gift.” The team also provided a further US$2,500 compensation to the “fixer,” who still had no idea he was working with undercover journalists.

It was clear to everyone on the investigation team that corruption in football was, indeed, endemic. In fact, it was so much a part of the fabric of the game that officials at every level referred to it as “relationship building.”

The investigation reached its apex when Anas and his team used three months to plan and convince the president of the Ghana Football Association, the second-highest executive in all of African Football and a FIFA Executive, that a wealthy businessman with ties to royalty wanted to do a sponsorship deal with Ghana’s Football Association. After setting the president up in a luxury hotel, they recorded him on camera accepting US$65,000 in cash as a gift — which FIFA regulations clearly state is unacceptable — and explaining to the team how he would take a 20% cut of a US$15 million deal. He said he would hide the cash by laundering it through a shell company. His total take would be roughly $4.5 million.

They had everything they needed.

When it was all said and done, 110 officials and executives were captured on camera accepting money from undercover reporters. In total, 150 payments were made. Only three people that were approached declined the cash they were offered.

The Documentary Debuts

The final documentary was called “12,” as in the “12th man” in African football, which in this case was corruption. Prior to its airing, Anas met with a team of lawyers to make sure they understood what evidence he had, what consequences — legal and otherwise — he could face, and what protections he might need.

In the days leading up to the premiere of the documentary, as word got out that it was a bombshell investigation into corruption in the country’s football structure, at least one government official, Kennedy Agyapong, was calling for Anas to be publicly hanged. But Agyapong didn’t stop there. After “12” had aired, he showed photos on TV of one of the reporters in Anas’ team, Ahmed Husein Suale, who had helped set up the final sponsorship sting. Agyapong said Suale should be beaten on sight. He even offered money to those who decided to take retribution into their own hands. It was remarkably similar to when a former President of the United States offered to pay the legal fees of any of his supporters who assaulted a journalist who went against him.

But unlike President Trump, some of Agyapong’s supporters took him up on that offer.

In January 2019, almost a year after the documentary aired, Husein was shot and killed by unknown gunmen while driving his car early one morning. The killing sent shockwaves across Ghana. Anas, shaken but undeterred, tweeted, “You were killed in the pursuit of truth. We will never forget. We will fight till justice prevails.” As someone who has been in this industry for a quarter century, I can’t help but wonder if, in his dying moments, Suale was at peace knowing that this level of violence was part of the accepted consequences of his work.

Agyapong himself denied he had any connection to the murder or bore any responsibility for it. Despite some arrests, the gunmen have never been openly identified, charged, or convicted.

But the work Suale did resulted in a fundamental change in Ghana and across the African football landscape. After “12” aired, the president of Ghana dissolved the Ghana Football Association, and all soccer matches in the country were called off. The association’s executive committee dismantled the referee’s committee, firing every official caught accepting a bribe. The association’s president was also found guilty of bribery, corruption, and conflict of interest in a FIFA ethics investigation. He was subsequently banned from the game for life after resigning his roles as association president, vice-president of African soccer, and his executive role within FIFA.

To this day, he maintains he was set up by people within the football association who wanted him ousted. He alleges Anas and his team were paid to investigate him and that Anas tried to blackmail him afterward, asking for $150,000 to keep the video from going public. Anas has denied the claims and told anyone who thought he was guilty of taking money to prove it.

So far, there is no proof to be had.

Methods Called Into Question

One of the main criticisms of Anas’ work involves entrapment. Did he trick someone into committing a crime? Some Ghanaian lawyers said he should be held accountable for his methods, with one going so far as to say that Anas is just as guilty as the person who takes his money because he is enticing them to compromise themselves by waving money in their faces. Anas refutes that notion by saying he simply holds out his arm, the perpetrator — the one who knows what the rules are — is the one who decides to take the cash.

There is little doubt that without this style of undercover work, none of the corruption they discovered would have ever been exposed. Did they need to go to the lengths they did and to the levels within the game that they did? Likely not. The more you do, the more risk there is involved — and the danger is also magnified the further up the chain you go. What would have happened to their investigation if they’d been caught by one of the international officials? Or by the president of the GFA? What would that have done to the rest of their undercover work?

At the same time, it is also hard to argue that putting yourself and others in that much potential peril for a story of this magnitude did not accomplish something good. But was it worth Suale’s life? Only Anas and his team can answer that. They’re the only ones that have to live with the consequences.

As for his methods, the National Media Commission of Ghana has publicly stated they have no issue with how Anas gathers and exposes corruption because Ghana law permits undercover journalism. UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan helped promote the documentary, praising Anas and his work, and even the vice-president of Ghana has defended his methodology and urged him to continue this kind of undercover journalism work.

And while Anas does not openly discuss the dangers of what he does, there are constant threats to his life in Ghana by officials like Agyapong, reinforcing the need for anonymity — and for Anas’s work to continue. The price for such work is obviously a very high one — a member of his team was murdered. But based on his response to it, Anas and his team know exactly what the consequences of their reporting are and feel the truths they are uncovering — and the subsequent change associated with it — are worth the risks.