(LOS ANGELES)— It was almost 2 a.m. when members of the Glendale California Planning Commission were finally able to cast their votes. For six hours, the commission had heard arguments from both sides on the proposed expansion of a luxury development in the Verdugo Mountains called Oakmont V.

Environmentalists and community members had been fighting the developer, Gregg’s Artistic Homes, for decades. This was Round Five. The developers had so far been successful in building Oakmont, but tonight, March 1, 2002, would decide the fate of the final part of the project.

Six hundred people came to witness the vote. To many people’s surprise, the commission recommended stopping Oakmont V. Lawsuits from Gregg’s Artistic Homes followed. And less than a year later, the City of Glendale, along with the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy, bought the land from the developers to be preserved as open, public space.

The community saved a mountain.

A New Challenge

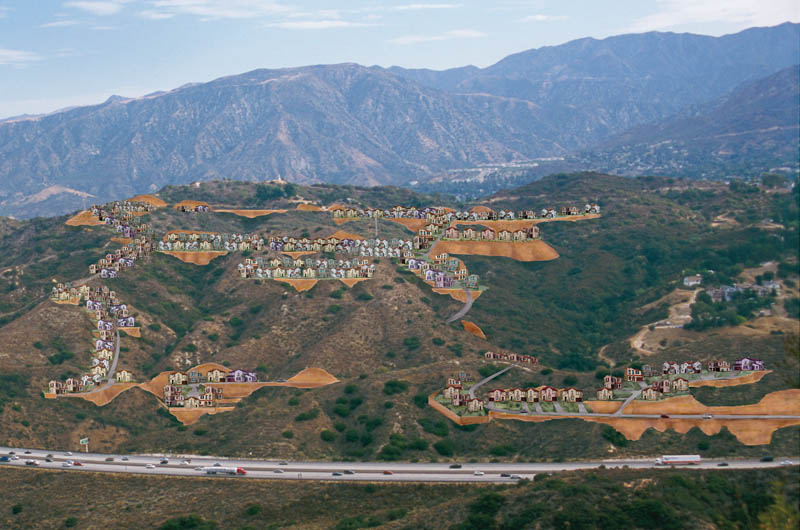

Verdugo Mountains [Credit: Kate Mays]

But this time, the project was approved. The city council gave the developers 20 years to build their luxury homes, to be called Canyon Hills, on 300 acres of the Verdugo Mountains.

The site for the Canyon Hills development remained untouched by WhiteBird for 18 years. Now, with the 20-year deadline to develop approaching, the developers have started the construction process by filing grading permits.

Enter Tujunga residents Emma Kemp and Mateo Altman, partners who have been concerned with protecting the land and its wildlife. They got wind of the project and quickly created the No Canyon Hills (NCH) coalition to stop the development in the Verdugos, just like the Oakmont V.

Oakmont V was a win for the environmentalists in Los Angeles. Halting the

development took years and cost the city millions of dollars. Likewise, No Canyon Hills is ready for a prolonged battle if that’s what it takes.

The clock is ticking.

“Drive around Southern California, does it look like the environmentalists are winning?” says biologist and advisor to NCH Dr. Dan Cooper bluntly.

Kemp, a team of experts, and community members are trying to save the mountain before WhiteBird’s permits are approved by the city and construction begins. If they fail to do so, hundreds of species will lose their homes.

350 Species

The Verdugo Mountains, a small range nestled in Northeast Los Angeles, are bordered by residential neighborhoods and divided by Interstate 210.

The proposed Canyon Hills site would require grading, or flattening, 300 acres of the Verdugos and would destroy the habitat of, according to NCH’s estimation, over 350 species of plants and animals, including a dozen designated as protected or threatened.

The development would also block a wildlife corridor that runs under the 210 which would cut off a crucial path for the animals of the Verdugos.

Artist rendering of the Canyon Hills development. [Credit: Friends of the Verdugo]

No Canyon Hills is especially concerned about cutting off the corridor for La Puma Tuna, the unofficial mascot of NCH. La Puma Tuna is a young male cougar that has been spotted wandering around the project site. Cougars are a vulnerable population in California– experts don’t know exactly how many cougars live in California but they estimate around 4,500. Cars hitting cougars on California highways have reportedly caused over 535 deaths in the last eight years.

A Changing Environment

When the WhiteBird developers first proposed this project in 2003, the Verdugos’ ecosystem was different– which is one of the reasons NCH wants the development plan to be revisited by the city.

NCH is currently petitioning for an updated Environmental Impact Report (EIR) of the site, saying that based on its research, the land is home to several rare and endangered species— including the Crotch’s Bumble Bee which has rarely been witnessed anywhere— and larger animals like cougars.

The EIR can make or break a development. Experts walk through the area and take notes on all the flora and fauna they see, paying special attention to rare or endangered plants and animals.

As required, experts conducted an EIR of the land before the project can be approved. The 2004 EIR found that the development would have no significant impact on the ecosystem. This is the first hurdle for NCH. If the Canyon Hills development wouldn’t have a profound effect on the flora and fauna of the area, then what’s the issue?

Well, the land has changed drastically, experts say.

La Tuna Fire burning in the Verdugo Mountains. [Credit: Scott L]

“It’s an important ecological driver,” says Naomi Fraga, director of conservation at the California Botanic Garden. “You know, it promotes these species that otherwise are living in the soil waiting for the fire to happen.”

Another reason NCH is asking for a subsequent EIR is because it’s likely the original EIR wasn’t conducted as thoroughly as it could have been– a lot of them aren’t, according to Cooper

“It’s like when you go for your physical exam, the doctor will kind of check you out, take your pulse, check your breathing,” Cooper says. “But they won’t keep you overnight and give you every battery of tests because that’s just not what you went in for.”

Besides using legal channels to delay WhiteBird’s permit approvals and request the subsequent Environmental Impact Report, NCH is taking a more unique approach to stop the development: crowdfunding to buy the land from the developers. It sounds strange– buying a mountain. But so far it’s working. Of the $25 million required to buy the Canyon Hills site, NCH has raised $12 million by partnering with the Trust for Public Land.

And if it is successful in buying the land, NCH will do something novel with it.

The Verdugo Mountains were originally Tongva and Tataviam native land. If saved, the land will be given back to the Tongva and Tataviam land conservancies.

The Coalition

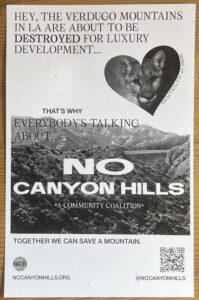

No Canyon Hills flier designed by Emma Kemp. [Credit: Kate Mays]

Kemp used her art and design skills to create an eye-catching Instagram account and website to get the word out about the project. And it worked.

“That was the extent of it,” Kemp said. “So it’s pretty surprising it’s getting this much attention.”

NCH is now a formal non-profit. In just six months, the No Canyon Hills coalition has garnered mass community support– almost 200,000 have signed a petition– and made real strides to stop the development.

The People

In the middle of a Zoom interview about what’s happening with the Verdugos, Cooper stops talking— staring out his window he pulls up a pair of binoculars.

“Sorry, I’m distracted,” he says. “Put the bird drip on and now birds are coming in.”

Saving a mountain takes a lot of time, work, and dedicated experts. Cooper is just one of them.

Devon Christen, the director of field research, got involved with NCH after seeing an Instagram post. He became interested in botany during the pandemic after researching how to keep his houseplants alive.

Devon Christen presenting his findings [Credit: Kate Mays]

Even with the community and experts on its side, NCH is still up against developers with deep pockets and the Los Angeles City Council, which seems to have different priorities.

“They want more development. They want more housing,” Cooper said. “They want more tax base, more assets, more amenities, more high- end housing so they can point out that ‘Hey, we’re this high-end luxury development that has so much disposable income. You want to locate your family or your business here?’”

The future of the Verdugos is uncertain. No Canyon Hills got bigger than Kemp ever imagined, but she still thinks of it as a small coalition and believes that community is the key to stopping the Canyon Hills houses.

At the moment, she is winning. The project site remains a quiet oasis in a big city, where previously unknown plants and animals flourish, and La Tuna Puma is free to roam.