(ALEXANDRIA, Egypt) — The Sway may never have had their rock star breakthrough in the 80s, but they were loved throughout the United Kingdom.

Bass player Paul Hogan recalls performing a gig in London where an Argentine fan attended their concert after receiving a cassette tape from a friend he was visiting. “The guy came over to see his friend and found out we were playing,” recalls Sway singer David Casson. “He brought his tape with him.”

Moments like this made band life worthwhile. Despite a hectic routine—cramped van rides with equipment, hours of driving, long sound checks, and playing two sets an hour with no pay—they loved gigging. They enjoyed meeting new people.

Then the financial struggles hit. “I left the band because I was making no money,” Casson explains. “I was 24, 25, looking around, thinking, If I don’t make money soon, I’m going to be skimping for the rest of my life.” On top of that, their albums weren’t available in stores, nor were they selling. Casson would visit places like the Virgin Megastore in the UK and see nothing but dust on the shelves.

“Our records wouldn’t be there. The next day, it’s not there, and the week after, it’s still missing,” he says. “You think, ‘Why am I doing all this hard work? Why am I recording?’ It takes six months to record these tracks, and nobody can hear them.”

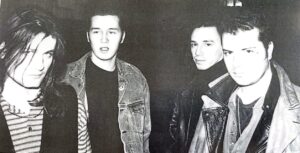

The Sway back in the day outside their rehearsal room circa 1992. [Photo courtesy of The Sway]

Over the past three years, The Sway took the time to reconnect, rediscover their sound, and write new music. Last year, they released their four-track EP Songs for Then and Now and began slowly re-releasing their back catalogue at the start of 2025, attracting a new set of listeners while catering to their day one fans.

This summer, they plan to record a new single to maintain the momentum.But this time, they’re older and wiser. They don’t need to be rockstars (although they won’t shy away from it). They just want to do music comfortably. Their expectations are more tempered.“We want to be rock stars for the weekend on a much more reserved level and come away with a great record for people to add to their growing collection,” says Hogan. “We want to be that band of brothers that we always were.”

Heaven’s Echo long ago

Before becoming The Sway, Hogan, Casson, and Kelly were known as Heaven’s Echo. They formed in the summer of 1989 and played for 18 months. The band took its name from one of their favorite bands, Echo and the Bunnymen, and that band’s second album, Heaven Up Here. Echo and the Bunnymen heavily influenced their early sound, from thumping bass lines down to rolling drums and jagged strings.

As Heaven’s Echo, the trio recorded a track for a compilation titled The Vinyl Underground, alongside other London-based artists. After a while, they felt creatively restricted. They wanted their music to be more melodic.

Introducing The Sway

James Kook joined the band as a guitarist in 1991, and they changed their name to The Sway. Casson was inspired by a Percy Shelley poem, ‘The Revolt of Islam,” which included the line “I felt the sway.” They settled on the name and never looked back.

Kook added flair to the band. Although he wasn’t classically trained, he brought ingenuity, creating stunning guitar solos that naturally advanced The Sway’s sound. Transitioning from a trio to a quartet gave them more flexibility and room to play. “When we were touring, and we’d get reviews back from the universities we’ve played or the gigs we played, people would say, ‘You sound very similar to U2 or The Cure,” Hogan recalls.

The Sway reunites in 2024 for rehearsals for their album, “For Songs Then and Now.” [Photo courtesy of The Sway]

Their first manager, Dave Evans, helped them book studio time and gigs, most of which were held at Evans’ South London nightclub. The band eventually parted ways with Evans due to limited opportunities. Eventually, they started rehearsing in a studio in Mill House, North London, owned by Roger Tichborne, who would pop in during the last 10 minutes of their rehearsals to watch.

Initially hired as their manager, Tichborne was a big help, securing gigs for The Sway in North London. One record company was blown away and wanted to pick up one of their albums, Silk. Tichborne advised them to go with the more established label, Bad Habits, for more financial support. Recording Silk allowed the band members to take a break from touring, which had become one of their biggest sources of stress. “We carried penniless,” says Casson. “But happy we had our cred.”

One of the band’s earliest believers was Hogan’s friend, Matt Redgrave, who became their roadie. He carried the equipment and the band around London in his bright orange Volkswagen camper, decorated with cartoons like Calvin and Hobbes, a TV show about a kid and his pet tiger. Although exhausting, Redgrave loved driving with the band and watching their gigs; it was a massive adventure.

“I looked at them and thought, you know, they might get a single out,” he recalls. “They might even be on ‘Top Of The Pops.’”

The band disbands

Each member processed the disbandment differently.

For Hogan, the band had become his family. After his parents’ divorce during his teenage years, the band gave him the stability he needed. “I never lost the individuals, but going out on the road, being together—I think in hindsight we should have said let’s carry on and get rid of management,” he laments. “But because it was encompassing and we wanted to be famous, it was never a compromise at that time.”

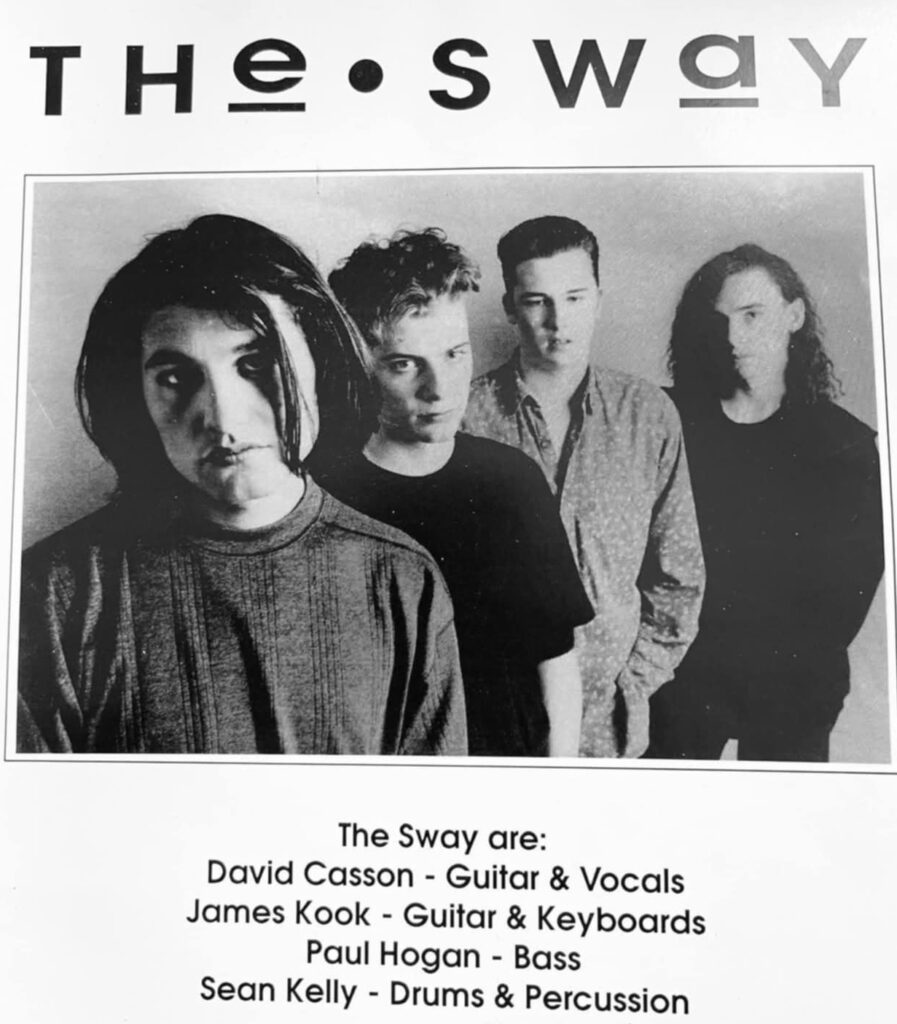

A press release photo of The Sway in 1993 for their EP “Silk.” [Photo courtesy of The Sway]

Hogan, Kelly and Kook continued without Casson, working with another singer and guitarist, but it wasn’t the same for Kook. “We’ve done the same recordings,” he says. “But it was never the same; it felt like we carried on just because we didn’t wanna do anything else.”

Eventually, that version of The Sway dissolved. Kelly moved on and joined Casson’s other band, President Rose, which garnered interest from record labels. Kelly left in 1999 to get married and settle down. Casson pursued a solo career, but whenever he got close to success, the band would dissolve, or members would leave. Taking matters into his own hands, he recorded a solo album, Forevermore, with Kelly contributing only on drums.

Kelly recalls, “It felt like we were about to sort of really take off. And then Brit-pop happened with Oasis, and it felt like music, especially in the U.K., took a slightly different turn.”

Comeback as The Sway

In 2008, Casson’s solo single “A Million Nights” was selected for a compilation album called Uncovered. David James, who selected the tracks for the festival, asked Casson to play at the Barnet Festival to promote the track. Casson reached out to Hogan, Kelly, and Kook, and they were all in. Just like that, The Sway was back, at least for a while.

Throughout the band’s ups and downs, Hogan battled with alcohol addiction, slipping in and out of sobriety. His struggles persisted during their active years, but after performing at the Barnet Festival with Casson and the rest of the band in 2008, he entered a more stable period. By the time the band reunited in 2011, he’d found his footing.

Hogan, now sober and focused, was ready to give music another shot. Together, they recorded When Worlds Collide. But not long after, in 2012, Hogan faced another battle with sobriety. Fortunately, this time, he chose to recommit to staying clean. Ten years later, in 2022, Hogan’s wife, Jenni, contacted the band members to surprise him on his tenth sobriety anniversary.

“The guys were waiting for me, and we’d been a bit wishy-washy with each other for a few years,” Hogan remembers. “David had moved away, Sean into golf, and Jim had always been a solitary animal when not in party mode. But it was a significant thing we got together; it was like old times.”

These days, even as the band enjoys creative freedom, Hogan still feels some lingering regret. “If I could rewind time, that’s what it should’ve been about; it should have been about the music,” he says. “I wish I’d worked harder back in the day rather than pretending to be a pop star, and I’ve apologized to the boys for that.”

The Sway in a band rehearsal practicing for their 2024 album “For Songs Then and Now.” [Photo courtesy of The Sway]

Kelly takes it more in stride. “I guess everything has a plan. If it had taken a slightly different turn, I might not be sitting here,” he says. “I might be in a mansion in Hollywood—or I might be in the graveyard up the road. Who knows?”

Despite the wild ride of disbanding, reuniting, living solo lives, and finding each other again, Casson still allows himself to dream. “A little daydream,” he says. “Maybe someone will go, that is amazing, and we need to get these guys on a three-album deal. I know they’re old men, let’s give them two albums or whatever.”

Then, he’s back to reality: “That will never happen, but we can dream, and we can at least do our part and make the record as good as it can be.”