(BATTLE GROUND, Wash.) – Dusty Mason didn’t want to be a nurse — at least, not at first. As we sit at the red 1950s dinette table she gave me, our respective spouses relegated to another room, my mom recalls how she got into healthcare. “I always thought that I would go to school and become a teacher,” she says. But her family was poor, and college was not an immediate option. Instead, after graduating from Easton High School in 1971, Dusty went to work.

She started out doing “odd jobs,” from grocery clerk to stewardess trainee. I try to imagine the woman who gets visibly nervous on planes as a stewardess. At 70 years old, my mom doesn’t look it, with an infectious smile and rosy cheeks framed by long, brown hair with just a hint of grey.

Dusty had come of age at the tail end of the Civil Rights movement, amid Vietnam and the anti-war protests. The fifth of seven children, her folks were too busy providing for their brood to be too invested in politics. Her dad voted for one party, her mom for the other — so it balanced out. Her oldest brother went to war, her youngest brother jammed out to Uriah Heep. Some of her friends burned flags, others got married or went to work.

Student protesters marched down Langdon Street at the University of Wisconsin-Madison during the Vietnam War era. [credit: UW Digital Collections]

The experience was jarring. She had never cared for elderly or sick people, and had never been around death. “It was such an education, such a shock—but somehow I fell into it,” she said. “I found that I had so much compassion for these people.”

She got married in 1973, and started working at a children’s home with her husband, Rich, who was a counselor. While she found that working with “deprived and neglected kids” took a high emotional toll, Dusty felt called to nursing. She decided to answer, going to nursing school to become an LPN.

Hitting the Road

Grand Canyon National Park, circa 1976 [credit: Barbara Ann Spengler / Flickr]

There, she worked for a time as a physical therapy aide. This meant caring for folks with mobility disabilities. It was physically demanding, helping paraplegic and quadriplegic patients into and out of beds and wheelchairs. But she enjoyed it and even figured out how to take one of the patients to an opera once, to their mutual delight.

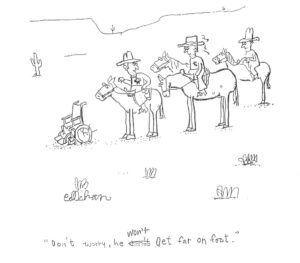

One of her patients was controversial cartoonist John Callahan. Working in physical therapy and pursuing her RN certification at Portland Community College (PCC) was a lot, and she and Rich separated along the way.

An accident in 1972 left Callahan paralyzed, and he subsequently became one of the Pacific Northwest’s most acclaimed cartoonists. His work often dealt with the subject of disability and appeared in Portland’s Willamette Week from 1983 until his death in 2010. [credit: John Callahan]

By the time the couple returned to the Pacific Northwest, Dusty had experienced several kinds of medical care. “I could not deal with sick children,” she admitted. “Every death is a heartbreak, but a child…” she trailed off. It was too much. How could it not be? “Neo-natal nurses are my heroes.” She landed a position with St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Vancouver, WA, floating from ward to ward for a while. “One night, I floated into the ICU, Intensive Care Unit,” and she never looked back.

At the ICU, Dusty really hit her stride. The pace and urgency were like a high. “There was so much adrenaline, almost constantly,” she explained. “It was like M.A.S.H. Patients were coding, their hearts were stopping, they stopped breathing. We did a ton of resuscitations.” Dusty realized that she thrived in this high-stakes atmosphere. Even though it was physically and emotionally draining, she was saving people.

There were trade-offs. “I think I was a little bit difficult, a little bit over-protective,” she reflected, and her schedule meant little time to spend with the family. James, by this time a violin bow craftsman as well as musician, had a more flexible schedule and shouldered much of the burden of myself and my brother, Brian. “I would come home and unload the whole evening onto James, then I would promptly pass out, and he’d be laying there like, holy shit!”

Dusty and James Mason, kissing on the dance floor [credit: The Ashokan Center]

Dusty spent 35 years at St. Joseph’s and its later iterations, retiring in 2017. She wishes better care could be provided to everyone as a basic right, rather than moving in the opposite direction. At times, she regretted not becoming a doctor—although now she’s glad that she didn’t sacrifice more of her life.

All told, she is happy that she found an outlet for her compassion, and gained the confidence to help so many. Personally, I am proud of the work my mom has done. She agrees, “I think it was a great career.”

Correction: A previous version of this article identified Dusty Mason as a licensed practical nurse (LPN). She is a registered nurse (RN).