( LAKE WORTH BEACH, Fla. ) — Nobody knows who, for sure, but somebody built a cinder block wall in Lake Worth, Florida in 1954, separating the Whispering Palms white neighborhood from what was once officially called the “Osborne Colored Addition.”

Eyewitnesses said that the city, now named Lake Worth Beach, built the wall. “Some years back, they were trying to say that the city didn’t have anything to do with it,” said Adella Bell, whose family has lived in the neighborhood for generations. “Well, there’s no documentation, but [my father] was not the only one that said they came down in city vehicles, in city uniforms.”

Over the past year, instead of tearing this 1,100-foot long, 6-foot high wall down, a community committee restored it, reinforced it, and repainted it with uplifting murals.

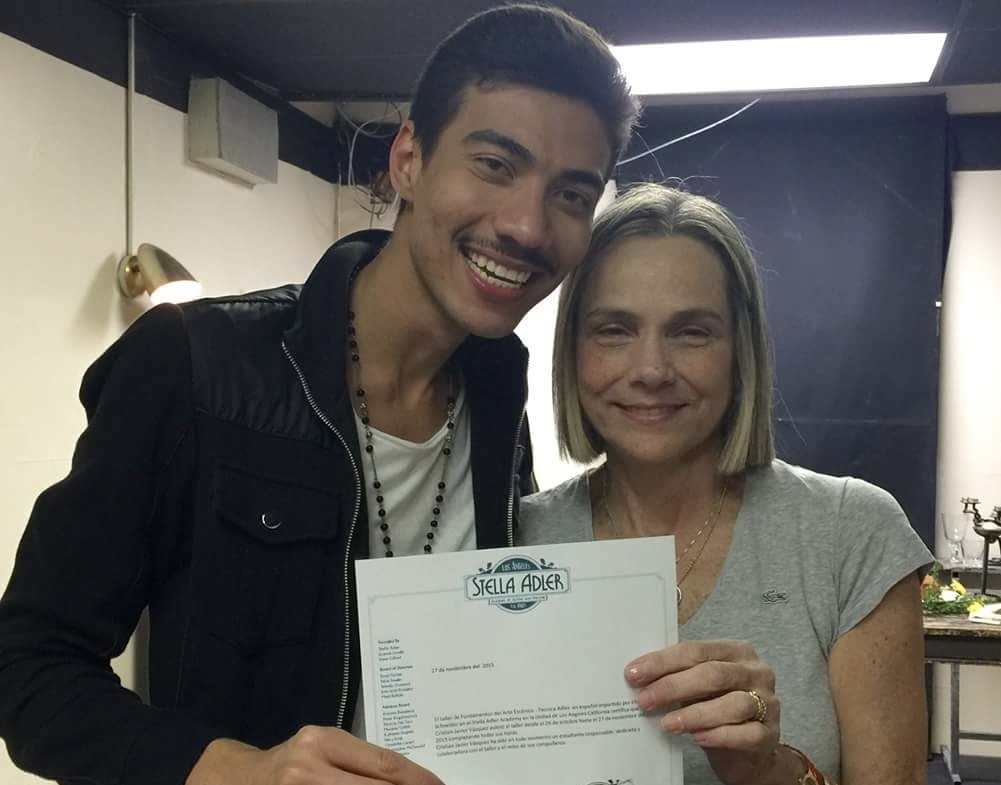

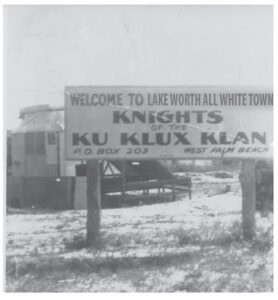

Ku Klux Klan sign declaring Lake Worth to be an all white town. [Credit: Historical Society of Lake Worth Beach]

Tony Cato, pastor of the New Hope Missionary Baptist Church, which is located one block south of the wall, agrees. “Because of what the wall represents, I would have by all means necessary, found a way to remove the wall.”

Despite the will of many to have the wall demolished, private ownership prevented it. “The wall is actually owned by the eight homeowners who live along the wall,” explained City Councilwoman Carla Blockson, co-chair of the restoration committee. “I love having the wall behind the house, because it allows protection,” explained Julius Jones, Sr., a Black homeowner who owns part of the wall, “but one thing, I would like for the wall to represent our people.”

Life in “The Quarters”

Lake Worth Beach lies immediately south of West Palm Beach. It has a bridge across the Intracoastal Waterway to its own public beach directly south of Palm Beach, an exclusive enclave that is home to the Kennedys, the Kochs, and the Trumps. Walls surround every estate, but those walls—unlike the segregation wall—were built to keep people out, not to keep people in.

The area was originally settled in the 1880s by a woman named Fannie James, a postmaster and former slave, according to Ted Brownstein’s “Pioneers of Jewell,” a history of the area that encompasses Lake Worth Beach. In 1913, it was incorporated as a whites-only district and its Black residents, including its original founder, were forced to move outside the city. The Ku Klux Klan posted a sign declaring Lake Worth an “all-white town.” (Disclosure, Brownstein is the author’s father.)

A 1926 Lake Worth Herald zoning code notice alerted residents that they would be levied a $500 fine for every day they lived in the wrong residential district. Other cities had similar walls during segregation including Miami’s Liberty City, Coconut Grove, and Pinewood neighborhoods, Melbourne, Florida, Detroit, Crane, Texas, Arlington, Virginia, and Ferguson, Missouri.

Adella Bell in front of the Unity Wall as painting progresses. [Credit: Ted Brownstein]

“That wall really meant that if you go on the other side … your life is in danger,” Cato said, “No matter what it is that you did, it’s basically over for you … because of the color of your skin.”

“You had to be in where you were supposed to be by six o’clock or like before the sun went down,” Bell said, “My mother used to work at a laundry up on Dixie [Highway] … when they would get off work, they had to get straight home because they had to be across that track and in there where they were supposed to be. … Otherwise, you would get in big trouble.”

“We called it ‘The Quarters.’ They said, you couldn’t go out of The Quarters,” she explained.

The railroad tracks that her mother rushed across still run along Dixie Highway, a block away. Heavy freight trains thunder through, shaking the ground.

Memories of violence connected to the wall continue to linger. “One lady I know says that every time she drives by [the wall] she gets a headache,” Bell said, “because she remembers some [violent] incidents that happened to her and her friends when they were, like, teenagers.”

“Coming home from school,” Trudy Lowe remembers, “one white person would tell their dogs to get us.”

‘Unity Makes Strength’

The wall stands on the western side of Wingfield Street. A well-landscaped median runs down the center. Industrial shops lie opposite. There is JA Custom Fabricators which fashions ornate gates and stairways mostly for wealthy clientele, Gomez Auto Repair, South Florida Aluminum, which manufactures “decorative shutters and ornamental metal products” also for wealthy residents, and a construction company. Further down is a soup kitchen named Above the Sea.

Over the decades, the neighborhoods integrated, according to Porsche Lowe, Trudy Lowe’s daughter. “This community now is a melting pot,” she said. “Everyone in here was dark-skinned. It’s not happening anymore. We have Black Americans; we have Hispanic; and, as a matter of fact, we have white. We have everyone.” The area is still segregated by income, however.

The restoration and murals are “all about making the community look like the rest of the city,” said Blockson.

Pastor Tony Cato preaching in his New Hope Missionary Baptist Church one block south of the wall. [Credit: Ted Brownstein]

Sara Gayoso depicted Lake Worth founder Fannie James.

Stephanie Stinchcomb painted a beach scene and hopes that people will “get a sense of the beauty of the area and what brings us all together.” “I love that they’re not tearing down the history,” she said, “They’re changing the narrative and making something beautiful out of something that was ugly.”

Hilary Mangel’s mural has giant wings with community symbols inside.

The mural that Lindsay McGlynn painted represents the city surviving COVID-19 with a young Black woman wearing a mask.

Trudy Lowe’s mother served on the community committee that originally renovated and painted murals on the wall in 1994. The city put up a sign renaming it the “Unity Wall.”

“I heard the horror stories or the not-good stories, but the name ‘Unity Wall’ … that’s what I can remember,” Porsche Lowe said. “So, I’d like the wall to stay because of the title. ‘Unity.’”

Cato has a different view, “I just don’t think words or anything like that can change the past or to cover the wounds.”

Bell wants to preserve the wall for “posterity to know what was happening.”

Before 1994, it was “just a cement wall. … I just remember a lot of squares,” said Bell, referring to the cinder blocks that comprise the wall.

Porsche remembers the 1994 renovation. “Dr. Martin Luther King was on there and a firetruck that I guess represented the first Black fire chief.” It was painted by students, and young people, she said who documented history, slavery, and oppression. The current renovation is an “upgrade,” she said, “with the pictures and the quality of the art” and “the quality of the paint.” Her mother, Trudy, also made sure that the renovation didn’t have murals documenting “so much of that old slavery history.”

Mixed messaging

City Councilwoman Carla Blockson, co-chair of the restoration committee [Credit: Ted Brownstein]

Carmelle Marcelin-Chapman, co-chair of the restoration committee with Blockson, explained that some didn’t want Black Lives Matter, “because of what the wall is representing now, as all of us united,” but “[All Lives Matter] is being used as retaliation to Black Lives Matter.”

Brent Bludworth—an art teacher at Lake Worth High School who painted the mural with portraits of Frederick Douglas, Martin Luther King, Barack Obama, and John Lewis—came up with a solution. He covered the “All Lives Matter” message with black paint and replaced it with the word “Unity.”

“It was divisive,” Bludworth said.“‘All Lives Matter’ includes everybody, but there’s still an argument that that’s not the issue right now in America. It’s that Black lives are being killed and profiled. … I wanted the message to be about unity.”

Despite calls for its demolition, the wall stands, for now, as a communal work of art with messages all can agree on.

It’s “a reminder of where we’ve been, but it’s (also) a reminder of where we’re going,” said Blockson. “Hopefully it’ll be a tourist destination. I want the wall to be so fantastic that people will say, ‘I want to go see it.’

Photo Gallery: Lake Worth Beach’s Unity Wall

!["I was born here in 1973. I've lived here my entire life, grew up at the beach surfing and scuba diving, all that, down at Lake Worth Beach. ... I do a lot of art that represents the ocean, sea creatures, that sort of thing," said artist Stephanie Stinchcomb. "[My painting] represents Lake Worth and Lake Worth Beach, and I think that everybody in the community, regardless of where they come from or what they've done can kind of look at it and get a sense of the beauty of the area and what brings us all together and brings us here."

"I think that we can use [art] to, instead of tearing down the history, to kind of give a different perspective on it and make something ugly, beautiful for everyone who lives around it, drives by it, sees it." Stephanie Stinchcomb's mural](https://theclick.news/wp-content/uploads/cache/2021/05/Stinch-scaled/841862590.jpg)

!["They came to me ... and they were like, 'Hey, we have a piece that we want you to do with your students,'" explained Brent Bludworth, art teacher at Lake Worth High School, "It had four photographs, one of Frederick Douglas, Obama, Martin Luther King, and John Lewis, and it had the All Lives Matter title on it. ... There were a few people that ... they felt it was racist. ... Words, you have to choose carefully, the message can get lost. ... That Monday, my wife and I went to breakfast and it just hit me ... the message is wrong. And so I went back on Tuesday evening after school and I had brought some black paint and I just erased it all, not the portraits, but the message and changed the message to Unity."

"I did a piece with one of the first ... Black surfers. His name was “Buttons” Kaluhiokalani from Hawaii. And I had a good image of him, like in the water with a peace sign. I thought that's cool, I can bring him to the beach, to this area of Lake Worth. ... I have Benny's On-The-Beach and the [Lake Worth] Pier in the background ... to kind of change the reference. ... We're not in Hawaii, we're in Lake Worth Beach." Brent Bludworth's mural](https://theclick.news/wp-content/uploads/cache/2021/05/Bludworth/1579119972.png)