SARASOTA, Fla. – Conversations halt and lights dim. A jazz tune from a live band is heard from backstage. Actors appear from all angles of the black box. They wear plaid and tweed suits, swing dresses and carry shopping bags. The set is painted with buildings of The Cotton Club, The Apollo and street signs, like the corner of Broadway and 142nd St. in New York.

The audience watches as a predominately Black cast from The Westcoast Black Theatre Troupe perform “Guys and Dolls.”

An Antithesis to the Great White Way

American theater has a diversity problem. In the last 150 years, there were 21 Black directors and 17 Black choreographers on Broadway, according to the Black Theater Coalition. The New York Daily News reported earlier this year that the moniker given to Broadway, the Great White Way, still represents Broadway’s predominantly white performances and performers.

Dr. Soyica Colbert, Idol Family Professor of African American Studies and Performing Arts at Georgetown University, has seen a change in Washington, D.C. Artistic Directors are retiring, creating space for people of color and women to advance. But The Great White Way still exists. “Historically, most productions on Broadway have had white people as leaders of the creative teams.”

The theater industry is too white. But, The Westcoast Black Theatre Troupe (WBTT) in Sarasota in paving the way for actors, directors and creators of color. The theater performs Black stories with Black actors. Simply put, it prioritizes Blackness.

14-year-old Samuel “Sammy” Waite performing at WBTT’s Stage of Discovery in 2020. [Credit: Sorcha Augustine]

The WBTT was created in 1999 by actor and director Nate Jacobs. The theater is in its 23rd season. This season launched with “Guys and Dolls,” and will be followed by “Flyin’ West,” “Dreamgirls,” “Big Sexy: The Fats Waller Revue” and a holiday show, “Black Nativity.” These shows focus on “the struggles and triumphs of people who sought to realize their own version of the American Dream,” according to the WBTT 2022-23 season announcement.

Nate Jacobs poses in The Donelly Theatre at the WBTT. [Credit: Evan Sigmund]

Jacobs’s predicament is common for theater start-ups. “Arts in the United States are generally underfunded,” said Colbert. “As a result, theaters and producers often present work that has a built-in audience or that is supported by grant funds.” Colbert said reliance on existing audiences makes it challenging for new, diverse voices in theater.

For Jacobs, the financial strain was overwhelming. He was in the process of shutting down the theater when he received a phone call from Jerry Springer, the popular daytime talk show host of “The Jerry Springer Show.” “He said, ‘Why are you shutting it down?” Jacobs explained. Springer sent a $10,000 check a week later.

The Donelly Theatre at the WBTT where “Guys and Dolls” was performed. [Credit: Lee Alisha Williams, October 2022]

The community supports WBTT. In 2019, WBTT raised $8 million for facility renovations.

A view from the road shows one of the renovated buildings on the WBTT campus. Executive Director Julie Leach says both buildings were historic warehouses from the 1920s and 1970s. [Credit: Lee Alisha Williams, October 2022]

Minstrel Shows, Blackface and Challenges to Black Stories

Blackface performances became popular in New York City during the 1830s. The National Museum of African American History (NMAAH) explained that these shows “characterized blacks as lazy, ignorant, superstitious, hypersexual and prone to thievery and cowardice.”

The NMAAH reports that Shirley Temple, Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney all wore Blackface. This connected “minstrel performance across generations” and resulted in minstrel shows and Blackface performers becoming “a family amusement.” The trend moved south, including to Sarasota, where minstrel shows were regularly performed and photographed in venues such as The Edwards Theater (now The Sarasota Opera House).

Minstrel shows and Blackface performances brought the Sarasota community together. Advertisements of these shows appeared in the Sarasota Harold-Tribune newspaper. One advertisement from 1927 says, “Blackface comedians will rule supreme and from the start to the finish of the show one round of laughter is assured.”

Nearly 70 years later, theaters still hadn’t figured out how to market to Black audiences. They also didn’t care. Jacobs felt this history of racism. He said theaters had “so much lack of interest” in attracting Black audiences. Their reasoning, he explained, was fear of low ticket sales and empty theaters. But, Jacobs proved this fear was wrong. The tickets for his first WBTT show in 1999 sold out.

Raleigh Mosely and Maicy Powell are starring as Joseph and Mary for WBTT’s upcoming holiday show, Black Nativity. [Credit: Sorcha Augustine]

The Troupe of the Westcoast Black Theatre

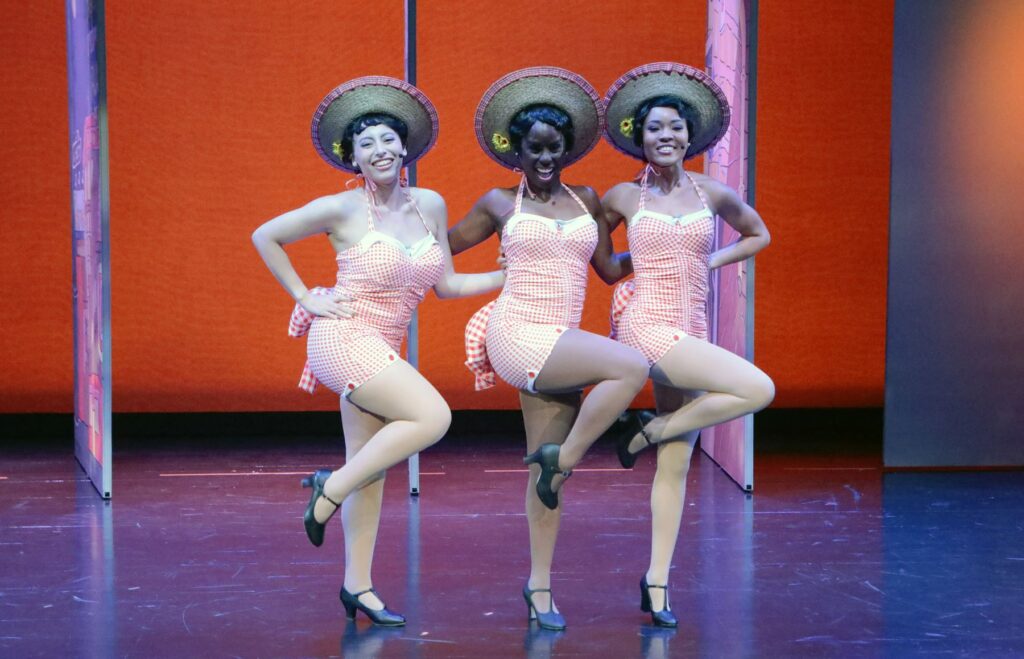

When the WBTT cast performs “Sit Down, You’re Rockin’ the Boat,” they evoke a Black church service on a Sunday afternoon. They stomp their feet and raise their hands in praise. The audience claps along. “This scene does not typically incorporate elements of the Black Church Experience,” said Brentney J, who starred as The Hot Box Girl and has been at WBTT since 2016.

The scene celebrates Blackness and Black culture. It contrasts with the often predominately white productions of “Guys and Dolls.”

An all-Black cast performed the play in the U.K. in 2017. The Playbill for the performance acknowledged a 1976 all-Black production of “Guys and Dolls” on Broadway. But there is no mention of an all-Black “Guys and Dolls” cast ever happening since. “We can take [a] traditionally white classic, like “Guys and Dolls,” said Jacobs, “and do just as well a job as any people. And we have done that.”

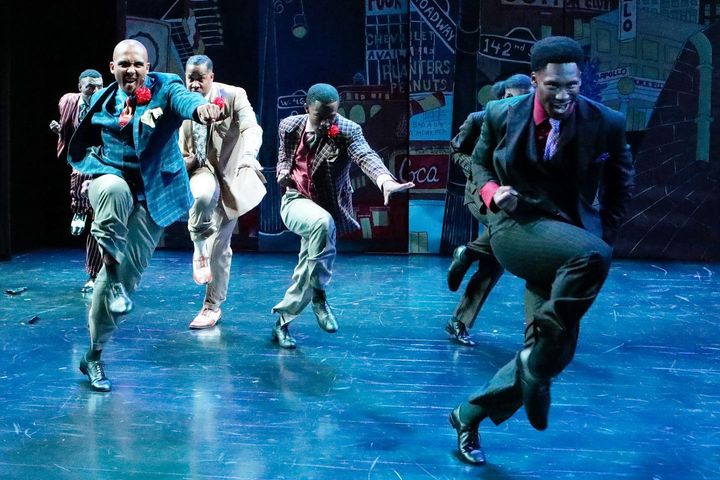

Dance captain and ensemble member Michael Charles bonded with the cast through their shared experiences as Black and people of color performers. This, he said, “makes it easier to come to work every day.”

Michael Charles, front, dances with castmates in “Guys and Dolls” at the WBTT. “Guys and Dolls” was the first show Charles performed with the WBTT. [Credit: Sorcha Augustine]

Maicy Powell on stage at the WBTT. In 2019, she performed an original one-person show, “The Kid is Alright: An Evening with Maicy Powell,” a part of the WBTT’s Young Artist Showcase. [Credit: Sorcha Augustine]

Raleigh Mosely, center in yellow, performing in “Joyful! Joyful!” at the WBTT. “The environment that WBTT nurtures and encourages lends itself to the familial type bond many people witness from the audience,” said Mosely about the warmness of WBTT. [Credit: Sorcha Augustine]

Brentney J, center in yellow, performs in “Broadway in Black” at the WBTT. [Credit: Sorcha Augustine]

“Guys and Dolls” concludes with WBTT actors joining each other on stage. They hold hands with wide smiles. Some wave and others bow at the applause. The audience cheers and each person stands. When the lights turn on, everyone takes their time gathering their things. The line moving out of the theater is slow.

No one wants to leave.

Jacobs is excited about the future of WBTT. “Anything you dare to dream, and you’re willing to put effort to work for is possible. And that’s Nate Jacobs’s story.”

Three framed WBTT articles from The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times sit on the wall in the lobby of the WBTT. [Credit: Lee Alisha Williams, November 2022]