There is a mural on Lexington Avenue anyone unfamiliar with East Harlem — or south of 96th street — will likely never stumble across. Mexican artist Frida Kahlo and Puerto Rican poet, Julia De Burgos, swathed in vivid gowns and bisected by bandoliers, wear their mighty hearts boastfully upon their breast and outstare anyone who dare look too long, all while holding hands. If you know where to look, just through the bars of decaying gate and wayward trails of vine, you’ll never pass it again without another glance. But if you don’t, despite the fact that the pair exist in near-plain sight, it’ll take a neighborhood authority to make you see. And there’s only one who will do it with a curse word and a heart as bold as the ones on the bricks. Her name is Debbie Quiñones.

It was fellow East Harlemite and mutual friend, Gloria Rivera, that first told me about the longtime organizer and community polymath in 2017. She spoke of Quiñones in hushed, almost reverent tones and referred to her as the stuff of living legends. Two years later, I finally meet the famous Quiñones after work at East Harlem Bottling Company, perhaps one of the only bars in El Barrio in which white men in flannel, backdropped by exposed brick and fairy lights, hold court. Seating herself, she slips into an empty table near the door because she has swagger without being a showoff. As we shake hands, I notice two things: she’s small – slight, even. Or, as she’ll put it later, “four feet with a six-foot shadow.” She also scares the shit out of me.

Photo: Audra Heinrichs

Last June, Quinones made news when she and a handful of Latinx activists stood in the lobby of El Museo del Barrio during the city’s annual Museum Mile Festival and read aloud from an open letter they called, The Mirror Manifesto. The document, first published in March following years of infighting within leadership and a series of controversial decisions made by the museum, demanded the institution better support the very communities it was created to serve. El Museo was intended to be a place of education, a celebration of culture and a mediator for the past and the present. What it has become, according to the manifesto, is “a market-driven endeavor,” and “an elitist institution for Latin American art.”

Established in 1969, El Museo was launched in a repurposed fire station where radical activists once held book burnings during the Nuyorican and Civil Rights movements before relocating to its current address on 5th Avenue. For Quinones, the museum’s recent missteps are indicative of more than poor direction. They represent a paradigm shift for the neighborhood and a prescience that its history might never be known as intimately as it deserves.

Quiñones’ protests are intensely personal. Her grandmother, Petrona Vega came to East Harlem from Puerto Rico in 1919. She was a maid-turned-bootlegger following the dissolution of her marriage, and ran numbers out of her home in the height of the prohibition era – all while raising Quinones’ mother. When she was caught some years later, it was Dutch Schultz, the famous Bronx-born gangster and crime boss, who made certain she didn’t end up in prison. She would remain in the neighborhood, as her daughter Olga would and now, as Debbie has.

El Nuevo Caribe, the first Puerto Rican political club in the United States and one of the few remaining clubs in New York City. Photo: Audra Heinrichs

Azael Quiñones, her father, migrated as a child from Arroyo, a small town on the southern coast of Puerto Rico, once known for its sugar production and now, the presence of the billion-dollar Stryker Corporation, a medical technology developer. Following the Jones-Shafroth Act, which made it legal for Puerto Rican citizens to obtain United States citizenship in 1917, thousands came to New York City, specifically East Harlem, Brooklyn and the Bronx. As a result, they formed social clubs in an effort to assimilate to stateside standards whilst holding fast to their own cultural identities. Each club represented a town in Puerto Rico. Quiñones’ father’s, Los Arroyanos Ausantos, or “The Absent Arroyanos,” is among one of her earliest memories. At first, the clubs were communities to gather – to play baseball in Central Park, dance, and hear the music they loved. They also provided services like help with translation for hospital visits and a number of social services. But most importantly, they would become weapons in an ongoing fight against gentrification and ultimately, mobilized Puerto Ricans into a formidable political force in the city.

“I still haven’t answered your first question,” she notes, about 40 minutes into our first meeting. “You asked how I became an organizer.” She’s right. But in all fairness, it didn’t happen right away.

Being the American-born daughter of proud Puerto Rican parents put her in a precarious social place – a situation common to the children of immigrants living in the United States. She grew up in a community that did its best to nurture Puerto Rican pride and instill it in the next generation, while also working, striving toward, and pursuing the elusive, often contradictory, American Dream. Reconciling seemingly conflicting identities is an inherently political act and the decision of which one to embrace put Quiñones at odds with the neighborhood she struggled to love.

She attended PS 171 and later the High School of Music and Art on 135th St., and while she agreed to learn the piano at the request of her mother – who had somehow found a way to get one up their five flight walkup – she played strictly classical music. No salsa. Her father, who was then working on a number of anti-poverty initiatives in the neighborhood, represented a lifestyle she wanted little to do with. “My attitude as a teenager was, ‘fuck community.”

The East River Housing Corporation on E 105 St. Photo: Audra Heinrichs

It wasn’t until after she graduated from both Lehman College and Le Cordon Bleu Culinary Institute, traveled and landed a job as a chef at the flagship location of Bloomingdales on 59th Street that the life she’d been avoiding finally found its entryway. Five months pregnant with her only child, Quiñones went into labor – on the job – and gave birth to a baby boy. She would never return to the kitchen. Instead, she took a job at the Department of Health devoted to the reduction of the infant mortality rate in predominantly Black and Brown communities like East Harlem. For a number of years, she came to find there was a systemic issue in her gravely underserved neighborhood. And it hasn’t changed. In a 2016 report released by the Health Department, the mortality rate for black infants still remains three times higher than white infants and for Puerto Rican New Yorkers, the rate is 1.3 times higher.

At the time Quiñones took the job at the Health Department, March of Dimes, a nonprofit founded by Franklin D. Roosevelt that purports to improve the health of mothers and babies, regularly released ads that ignored the blatant racial and socioeconomic factors that made pre-term birth a bonafide elemental fate. In an effort to shift the narrative, she and her colleagues began sex-positive reproductive health workshops that sought to educate the East Harlem on sex, pregnancy prevention and how to advocate for oneself in medical settings. It wasn’t long before she was asked by her boss to approach the neighborhood community board and propose a women’s committee that would expand upon and further those initiatives.

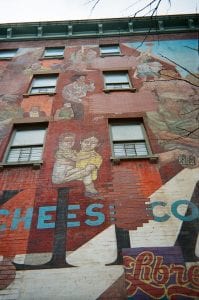

‘The Spirit of East Harlem,’ on the corner of Lexington Avenue and 104th Street. Originally commissioned by Church of the Living Hope and completed by Hank Prussing and Manny Vega in 1978. It was restored in 2009 after it was defaced by vandals. Photo: Audra Heinrichs

There are 66 community boards in the city of New York, each one purposed with learning every corner of its district, providing recommendations and resources on municipal services and the disposition of public land. Varying among them are a number of issues to be parsed out. In today’s East Harlem, there are three pressing ones: affordable housing, neighborhood preservation and employment. In 1987, when Quiñones was tasked with approaching the board and becoming a member, it was public safety and transportation, both of which made it impossible to establish “a little women’s committee,” as members – both men and women – put it. There was little interest and even less time as the AIDS crisis had only just begun to devastate East Harlem. Health officials would tell The New York Times in 1996, that one in every 35 adults in the neighborhood was infected with the virus. “East Harlem was dying. We were suffering,” she told me. “Looking back, I realize now I’ve witnessed so many movements and most of them were about fighting stigma.”

Much of her adult life has been spent at meetings. At one time, she was a member of 10 committees and attended 21 meetings a month with her young son in tow. “You’re literally building the neighborhood and you have a responsibility. But it becomes such a lifestyle that you don’t realize the magnitude.” Somewhere in 30 years spent on the community board, she got married, divorced and dated. She left boards, joined a few others – mostly related to community arts and education – and was approached to run for district leader, a proposal she declined. Her father passed away years ago, and only a month to the day we first spoke, she lost her mother, Olga, who she took care of until she passed. “We used to walk against traffic together down Park Avenue and I remember asking her, ‘Mom, why are we doing this?’ and she’d say, “Because sometimes, you gotta make your own road.”

A mosaic homage to Puerto Rican poet, Julia de Burgos, by Manny Vega as envisioned by Marina Ortiz and Quinones herself, in 2006. Located on East 106th Street between Lexington and Third Avenues. Photo: Audra Heinrichs

There have been wins, losses and due mostly to Quinones’ dogged advocacy, many more murals commissioned for East Harlem, according to friend and colleague, Marina Ortiz. She is still on three boards, works full time at the New York State Department of Health Aids Institute and last year, she received the Latina 50 Plus Lifetime Achievement award. She has renamed 13 streets in the neighborhood after Puerto Rican political forces and fallen friends. Her son has become a chef. Sometimes, she dances salsa on the weekends. And because of the Mirror Manifesto – now signed by well over 500 artists, writers, curators, community members and others – El Museo has established a new advisory board, some of which – El Museo confirmed – is comprised by the very activists that composed the Mirror Manifesto. Quinones, included. As Ortiz, puts it: “Debbie knows absolutely everybody in the neighborhood, from famous to poor. And people respect her for it.” Even still, she’s hoping for a role on the board of directors, which has also agreed to expand in 2020.

“Anything else?” Quiñones asks, effectively ending the first two hours we spent together. We decide to walk a few blocks, stopping only to discuss a few of the murals she’s commissioned and to take in what remains of her grandmother’s old home. Today, it sits shadowed by scaffolding – likely being transformed into apartments in which no less than two white tenants will hang a Black Lives Matter sign. I would know. The building sits beside my own.

We’re about to say goodbye when she mentions something about a cigarette and the universe supplying it. Not a second later, a man crosses the street and lights up. “Hey, can I get one of those?”

She looks back to me – brow raised, cigarette in hand – and says, “See?” And for the first time since I moved to the neighborhood over a year ago, I do:

Debbie Quiñones needs the Barrio. But it will always need her more.