(SEATTLE) — Fixed among NW 64th Street’s sidewalk stand two neighboring northern red oak trees believed to be over a hundred years old. The trees’ impressive heights and matching thinning red leaves would seem to imply that the oaks have had and will continue to share a longstanding similarity of circumstance.

However, sectioned off behind caution tape, makeshift metal fencing, and a smattering of orange traffic cones, one key ornament marks their newly diverging futures. While the rightmost tree boasts a neon green public notice sign, declaring the city’s intent to protect the tree, the leftmost wears a sign of yellow, signifying its impending removal.

![The yellow public notice sign marks the older of the two oaks slated for removal [Credit: Abbey O'Brien] Picture of a tree with a house behind it](https://theclick.news/wp-content/uploads/cache/2025/12/IMG_3310/2905793745.jpeg)

![A close-up of the yellow removal sign stapled to the eastern and older tree's trunk [Credit: Abbey O'Brien] Picture of yellow city sign on tree](https://theclick.news/wp-content/uploads/cache/2025/12/IMG_3104-1/2656693644.jpeg)

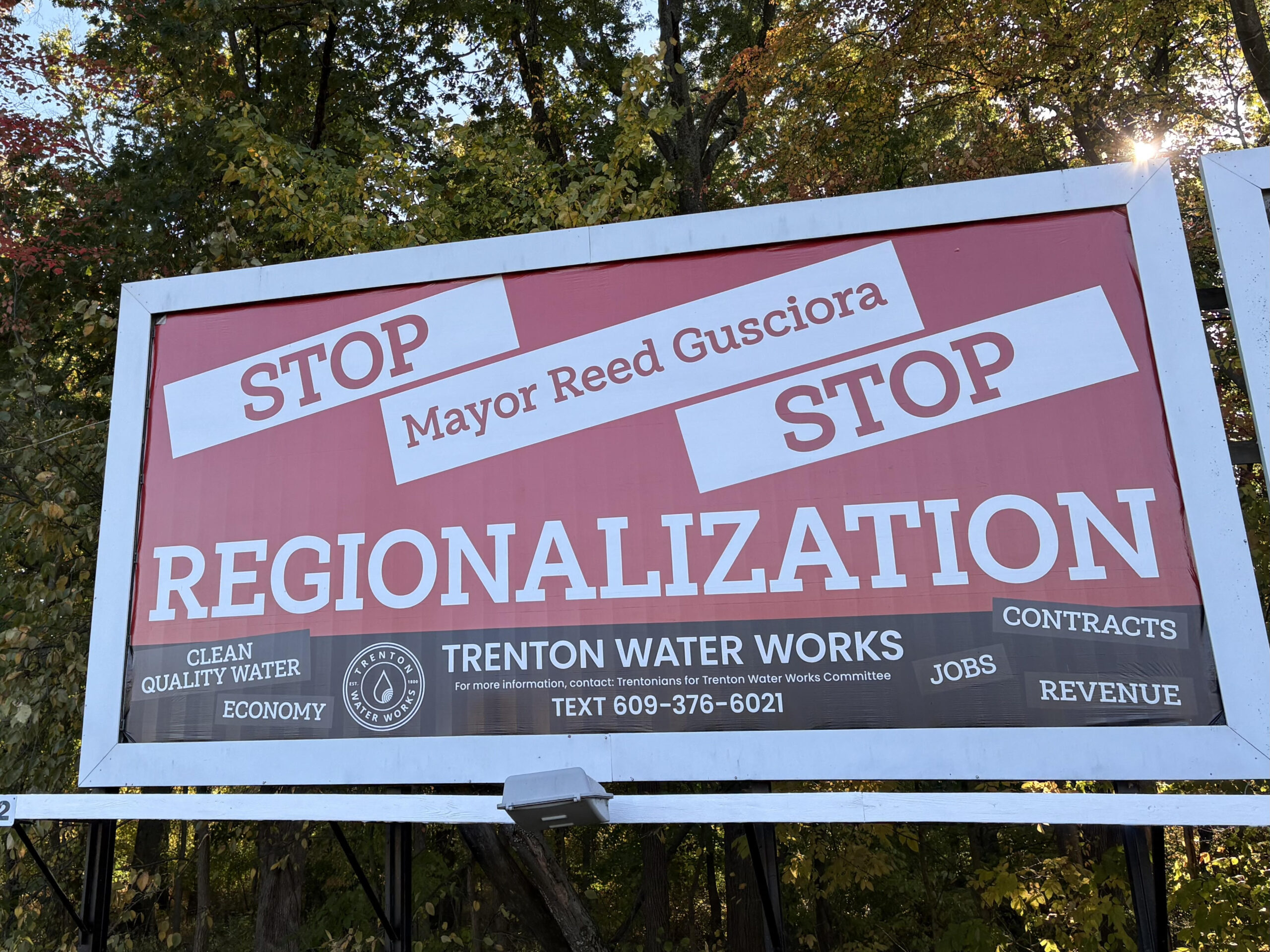

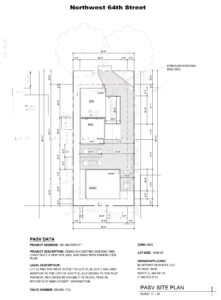

Affectionately named the “Ballard Twin Oaks” by local tree preservationists, the construction application submitted to the city back in April contained plans for a new single-family residence and accessory dwelling units to be built on the recently excavated lot. Within those plans, the driveway leading up to the development angled through the middle of the trees in such a way that they were both protected, a design decision aligned with the city’s tree preservation and community health goals of “30% canopy cover by 2037,” and one supporting Seattle’s “Emerald City” nickname.

When a new plan set was submitted later that summer, the driveway’s positioning changed to extend east, slating the easternmost and taller of the two trees for removal. In records obtained from city offices, no city official could account for the deviation, but one senior forester across the assessment presumed it was possible that the placement of the utility lines under the tree’s center, in addition to a potential future driveway through their roots, presented too much disruption.

“Its possible we wanted to be conservative and ensure we are saving at least one, the younger one being the better choice,” said the forester in city correspondence. But to those fighting for the oaks, the older tree’s sacrifice exemplified yet another instance in an ongoing citywide battle of balancing tree preservation with housing expansion in Seattle’s struggle to grow without losing its green.

A neighborhood on notice

Upon proceeding with the conceptual plans, the yellow sign was stapled to the oak’s trunk on Sept. 24, listing the tree as one that “cannot be successfully retained due to public or private construction or development conflict.”

The notice quickly drew the attention of Ballard residents. Within a day, the Seattle Department of Transportation’s (SDOT) Urban Forestry division, which oversees street trees, received 20 to 30 public comments opposed to the tree removal, according to city records.

“I am writing in strong opposition to this tree being removed,” wrote one fellow 64th Street resident. “The original permit submitted to City of Seattle for development on this property retained this tree. It makes no sense that the project cannot be constructed without removal.”

“The rate of tree removals in Seattle, Ballard in particular, is compromising the environment we all share,” emailed a third-generation Ballard local.

“The tree is part of our community,” said another resident.

By Sept. 30, Tree Action Seattle, an urban forest advocacy organization that boasts over 30 tree preservation campaigns and has tracked nearly 4,500 trees since its inception in 2023, launched an email campaign and began raising awareness for the Twin Oaks via its Instagram account.

“Usually, most of the trees that we stand up for are on private property. You don’t have to put a notice on a tree that you’re cutting on private property,” said Sandy Shettler, one of the lead organizers at Tree Action Seattle. “But street trees have to have notices posted on them for 14 days … Sometimes it just goes up, and it says this tree will come down … So this notice went up, and everyone’s like, ‘Wait, what the heck?’”

Tree Action Seattle community activists Andy Stewart and Sandy Shettler speak at a tree rally on the University of Washington campus on Nov. 9. [Credit: Abbey O’Brien]

The Twin Oaks twisted fate

Due to the twin trees’ proximity and age, the trees share an overhead canopy and likely a system of underground roots. In arboriculture, this could link their livelihood in a somewhat contested phenomenon that’s come to be known as the “wood-wide web,” in which trees exchange carbon, water, and nutrients via a subterranean network of roots and fungi. Should the Ballard Twin Oaks subscribe to this symbiotic arrangement, cutting down a twin tree already impacted by existing infrastructure could affect the odds for the survivor.

“One side of the tree has been protected, cooled … and then suddenly it’s exposed all by itself,” Shettler said. “It might survive, but then all those roots are going to be rotting underneath. Together with the construction impacts that it will have, it wouldn’t look good.”

Even if the twin trees survive as a pair, Shettler notes that vulnerable trees are at risk twice in any local development: once during planning, and again during construction. In the case of the oaks, each phase presents risks.

“It’s actually the development project itself that is concerning, because what we’re talking about is major machinery and heavy-duty equipment coming over those tree roots habitually for months,” said Kim Butler, a Seattle resident and known tree activist ever since her young son penned a petition that ended up extending the life of a bigleaf maple tree in the Green Lake neighborhood over twenty years ago.

“Only time would tell, but very likely, with that kind of weight on top of the root zones, without protection, it would have been a quid pro quo, basically. The trees would die, and that would forfeit this whole thing where they’re reviewing whether or not to save the trees,” added Butler.

Thankfully for the trees’ defenders, at the recommendation of a professional arborist who assessed the site early in the development process, the machinery pathway was recently shielded over with metal plating layered over a bed of wood chips.

Metal plating sits over wood chips to protect tree roots from machinery entering the development site. [Credit: Abbey O’Brien]

“They don’t usually take this long”

The required 14-day period for public notice closed in early October. By November, Shettler shared that “87 neighbors within a 2-block radius [were] actively monitoring the oaks,” and joining in Tree Action Seattle’s calls to save the trees and alter plans. At that point, the fact that the trees were even still standing was surprising.

“They don’t usually take this long, which is indicative of, I think, some of the things that have been brought up that they’re strongly contemplating alternatives for,” shared Butler.

With discussions ongoing and the potential for additional reviews, the permit for the oak’s removal has yet to be issued. But further analysis determined that the tree’s 44-inch diameter at breast height (dbh) — a measurement of a tree’s diameter a little over four feet above its base — places the tree closer to possibly 200 or so years old. The removal of a tree that mature frustrates many who feel that it represents another instance in which the city’s development practices are misaligned with its tree conservation goals.

The tree surrounded by wood and yellow tape is a mature northern red oak at risk of removal. [Credit: Abbey O’Brien]

When the city passed a controversial new tree ordinance in June of 2023, led in part by the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections (SDCI), the organization tasked with issuing construction permits, advocates feared that the real estate-friendly code severely threatened Seattle’s tree canopy. Over two years later, according to InvestigativeWest’s reporting, more than 2,500 trees have been removed for construction since the ordinance went into effect, and more than 2,000 were removed for other reasons. In some cases, removal numbers stood at over 73 per week.

“I think there’s a total lack of awareness. People think our trees are saved … It’s not actually happening,” said Butler.

Jessica Dixon, a local landscape designer and Seattle resident for over 30 years, shares her peers’ frustrations with removal practices and is among those encouraging the city to promote methods for housing and trees to coexist.

Jessica Dixon, a local landscape designer and tree advocate, holds a sign at the UW rally. [Credit: Abbey O’Brien]

Dixon also argues that residents might be distracted by the competing good-faith interests in building affordable housing vs. protecting trees. In many circumstances, she believes it’s not affordable housing being built.

“It shouldn’t be a housing or trees thing. A lot of the new housing that’s going in, where the trees are going down, are in more established neighborhoods,” said Dixon. “You’re getting market-rate, million-dollar homes. And so it is more housing, but it’s not affordable.”

A compromise of design

For the property nestled behind the Ballard Twin Oaks, valued at nearly $700,000 before its demolition, the developer involved in the project declined to comment when contacted by The Click. But the unexplained shift in the planned driveway’s positioning at the cost of the older twin embodies many advocates’ worries that city projects continue to default to removals and replantings rather than working around existing trees.

A protest sign at the UW rally calls for designing around trees. [Credit: Abbey O’Brien]

Activists believe that it doesn’t have to be an either-or situation. Instead, it can be a compromise of design. But for the inhabitants of the Emerald City, it has to start with residents like Ballard’s two tenured oak trees.

“In the end, 10 years down the road, when all these trees are gone, people are going to go, ‘What the heck happened?’” said Butler. “And then it’s going to be too late.”

![Wrapped in tape, a “Protect Tree” green sign designates the western, younger oak as the one to be retained [Credit: Abbey O'Brien] Picture of a tree with a green sign and surrounding fencing](https://theclick.news/wp-content/uploads/cache/2025/12/IMG_3301/1393116039.jpeg)

![A close-up of the green "Protect Tree" sign [Credit: Abbey O'Brien] Close-up of a green "Protect Tree" sign](https://theclick.news/wp-content/uploads/cache/2025/12/IMG_3103-2/2356436939.jpeg)

![Site aerial images showcasing existing utility lines [Credit: City of Seattle] Image of trees and an intersection](https://theclick.news/wp-content/uploads/cache/2025/12/Tree-Utilities-Image/459570886.jpeg)

![Revised site plans showing a new driveway alignment and removal of the eastern oak [Credit: City of Seattle] Building blueprint](https://theclick.news/wp-content/uploads/cache/2025/12/Revised-Plans/3048859818.jpeg)