(NEW YORK) — “Hey, Mom, I cannot see your Andrew Yang,” said Aidan of Chelmsford, Massachusetts. The 3-year-old boy pointed to the pin on his mother’s shirt. Mercyanne Publico, 39, picked up her son, and he gingerly traced the outline of the button shaped like the face of Andrew Yang, the 2020 Democratic presidential candidate, wearing a blue cap that reads “MATH.” MATH was Yang’s 2020 campaign slogan: Make America Think Harder.

Mercyanne Publico with her son Aidan.

[credit: Mercyanne Publico]

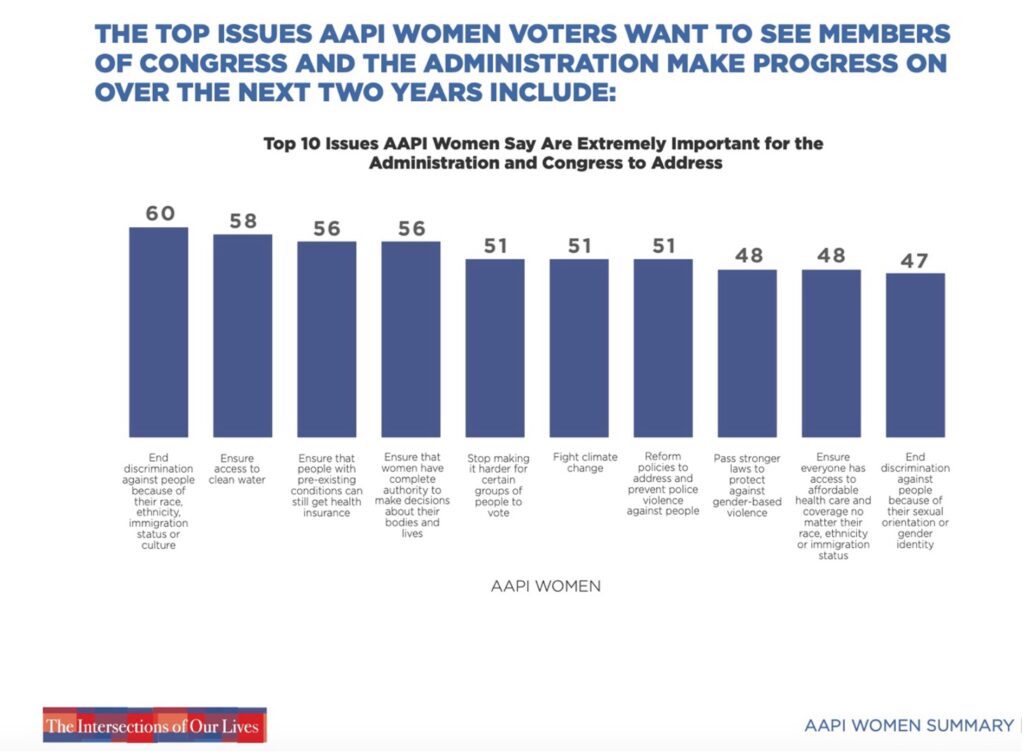

Born to Filipino and Chinese parents, Publico was terrified but not surprised that Trump’s tweets would have an impact on the safety of Asian Americans. Like 60% of Asian American women, surveyed this year by the non-profit collaborative Intersections of Our Lives, she hoped her vote would help stop discrimination.

A 2021 University of California at San Francisco study showed that social media activity is a “predictor of the formation of hate groups and the occurrence of hate crimes.” More than 11,500 hate incidents against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) were reported between March 2020 and March 2022 following Trump’s tweets — a 339% increase nationally.Publico throws her hands in the air as she retells the story of that time. “I was worried about Aidan because his eyes look so Chinese. What if he got bullied at school because of what other kids’ parents might be saying at home that they might overhear?”

Publico says she didn’t campaign for Yang simply because he was an Asian American. “Just because you’re Asian doesn’t mean I’m going to connect with you because I didn’t connect with Kamala Harris, and she’s Asian. She really pissed me off. I can’t tell you what her positions are.” Publico elaborates that the first Black and first Asian female vice president “swung where the sound bites swung.” With Yang out of the race, she voted for Biden but is considering not voting in the 2024 election.

Like 87% of AAPI women voters, New Yorker Erica Kim feels the stakes are too high not to vote. The 24-year-old procurement analyst recalls the pressure of voting for the first time in 2020. “If you’re not going to vote, you will get socially shamed.”

Kim grew up in a predominantly Asian neighborhood. However, she noticed in recent years that her community was anxious about holding cultural events because of anti-immigrant and anti-Asian sentiments.

“There’s a serious backlog for South Asians trying to become U.S. citizens,” Kim says. “My friend’s parents had been in the States for 10 years and had jobs but ended up moving to Montreal because they couldn’t wait any longer for their U.S. citizenship.”

Tugging on her gray Asian Boss Girl sweatshirt, Kim says, “For my parents, it was a fairly quick and easy process.” Her father immigrated to the U.S. from South Korea when he was seven years old. “My dad said his mom was asked two questions and became a U.S. citizen. Then he and his younger brother were naturalized.”

Erica Kim’s sweatshirt reads AsianBossGirl Collective. [credit: Jannelle Andes]

“I grew up a Latina. So even though I present as Asian, my values are very Latina. But that doesn’t exclude me from being Asian American as well,” Ventura says.

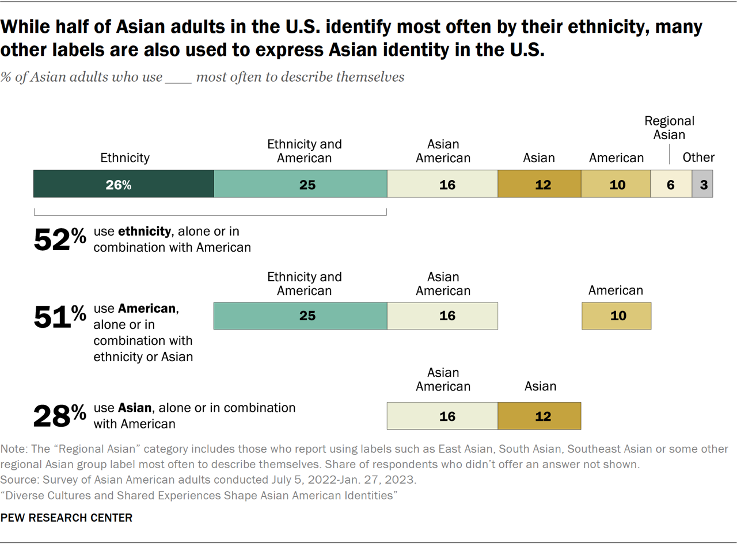

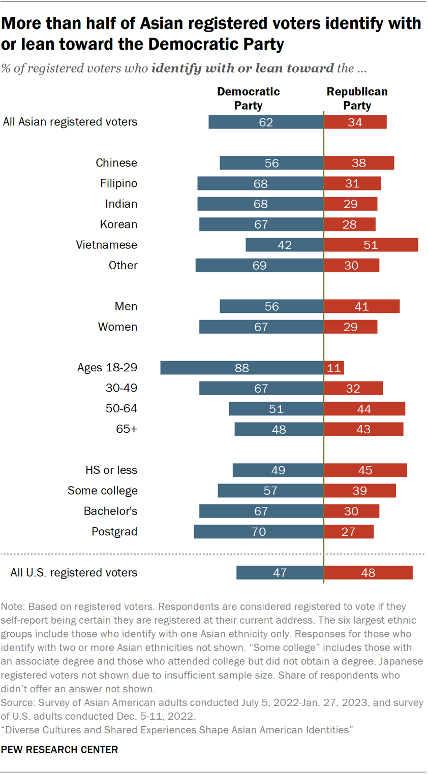

Ventura is not alone in relating to multiple identities. The Pew Research Center acknowledges that the Asian American population, which is the fastest-growing in the U.S., consists of “diverse cultures and shared experiences.” Only 16% of the population describe themselves as Asian Americans. About half label themselves based on their ethnicity or heritage, such as Chinese American or Indian American, while 10% say they consider themselves just American. The shared experiences that Pew found were the monolithic perception that non-Asian Americans had and the distress over racism or discrimination.

“There was this interplay between race and fears of discrimination. There was a feeling of not being welcomed,” Ventura says, her bright red lips forming a frown. “I just remember feeling anger, helplessness and a sense of injustice. I grew up thinking that the U.S. was this dream world. It was very disappointing to me that I fought so hard to be here and be a part of this fabric. And I don’t really like the pattern.”

Nikki, an Indian American graduate student at Rutgers University, also doesn’t like the change she has seen in America. Adjusting her cat-eyed glasses, she says that since Trump took office, “racism became more acceptable.”

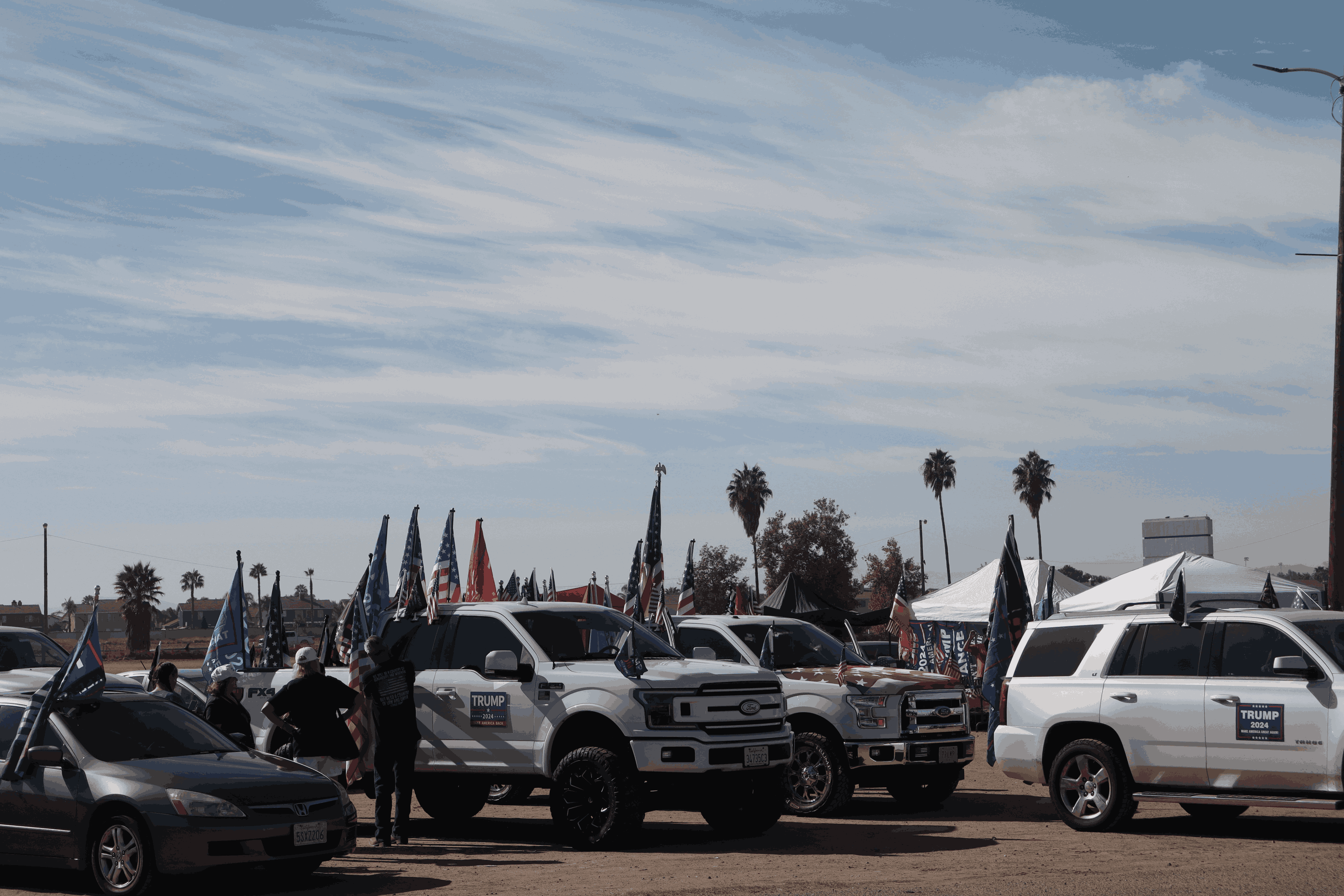

“It’s scary to think of another term of Trump, and he comes back with a vengeance,” Nikki says. “What if his supporters are more emboldened to be hostile? I would never want to move away from the United States. But if I feel like my life is at risk for just existing, that might be something I have to consider.”

Although she says she doesn’t really trust any candidate, the 23-year-old atheist agrees with President Biden’s campaign that Trump’s re-election would be “straight out of the Handmaid’s Tale.”

“It’s scary to think about the horror stories of women having miscarriages and then being investigated or not being able to get treatment because doctors are afraid to get prosecuted,” Nikki says. “What I look at for voting is reproductive rights, especially since those are in jeopardy now.”

Nikki is part of the 85% of AAPI women who want a candidate who supports their reproductive rights. However, she says, “I don’t think it’s uniquely an Asian American woman problem. It’s a problem for women in general.”

Janet De Jesus, a 64-year-old retiree, wants the younger generation to continue to challenge the status quo. Unlike the 67% of the Asian American female population who favor the Democratic Party, she admitted that she historically voted for Republicans. That changed in 2020.

This chart shows the break down of how registered Asian voters in the US tend to vote. [credit: Pew Research Center]

“I’m not crazy about Donald Trump — the way he spoke, talking about illegal aliens and who is allowed to stay in America,” De Jesus says. “There will be more hate if he’s re-elected, that’s what I’m scared of.”

The mom of three, who is of Filipino, Chinese and German descent, says, “One of my daughters is really outspoken. She’s into women’s rights, and I’m happy about that.”

Shaking her graying auburn hair, De Jesus says, “It’s time for a younger generation to take the lead. It doesn’t matter if they’re a man or woman, whatever ethnicity, whatever race.”

On a cold New England afternoon in February 2024, Publico’s son, Zed, walked into her office with his stuffed animal, Slothie. Behind the five-year-old was big brother, Aidan, who handed his mom a handwritten note with the words, “I love you, Mom.”

At that moment, Publico knew she was voting this year — for herself, her children and future generations.

Publico has a message to the presidential candidates: “When thinking about these policies or initiatives that you plan to represent or ignore, put your family in the shoes of other people. Put a face to those policies that you support or choose to ignore.”

Publico’s son Zed wears very American cowboy boots. [Credit: Mercyanne Publico]