(HELSINKI, Finland) – A familiar saying in Finland is that to be born there is like winning the lottery.

Any outsider peering in might agree: The Northern European nation has been named the happiest country in the world four times in a row now by the World Happiness Report. Among the long list of items that have contributed to this classification are a functional social security system, free education, accessible basic healthcare, a long life expectancy, and a feeling that the country is generally safe and non-corrupt.

However, most Finns don’t agree with the report’s findings — in fact, they might ask: “Really, us again? Why?”

Though the basic elements for a good life are there, a big problem that already existed before the pandemic has reared its head: Mental-health issues across all age groups that have been exacerbated by months of lockdowns and isolation.

Some Sad Statistics

The Finnish Partnership for Mental Health, which consists of 34 mental-health organizations, recently put together a report to the members of the Finnish parliament about the effects of the pandemic. It revealed that mental-health problems are the biggest reason for early retirement in case of reduced ability to work. It added that mental-health issues cost the government almost $13 billion a year.

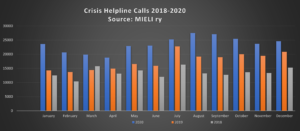

In July 2021, the National Crisis Helpline set a record when more than 28,000 people called for help in just that one month. The amount of calls has steadily increased over the previous years.

Calls to the Crisis Helpline have increased. [Source: Mieli ry. Credit: Sanna Voltti]

This stress has been recorded in various young-adult demographics. According to the School Health Promotion Study also conducted by THL, every third girl in secondary school or second-degree education is experiencing anxiety. Boys’ anxiety has also increased.

Recent statistics collected by Findicator show that young people’s suicide mortality in Finland is high by European comparison. Around 12 percent of all who died by suicide in 2020 were under 25.

The law says that people who are seeking help for their mental-health problems should get it during the first 90 days after an assessment of the need for care. However, this isn’t often feasible because of long waiting times. Recent statistics show that before the pandemic there were about 400 people continually waiting to get help for their problems after those 90 days. Now, the amount is over 1,000.

Young people aren’t the only ones suffering. THL released a statement in 2020 saying that the restrictions hampered the life of the elderly as well. Domiciliary care has been limited because of the isolation of seniors. Being home alone has caused a severe mental strain to the elderly, according to THL.

Loneliness Is a Problem

Helsinkimissio is a social-work organization based on voluntary work. It was founded in 1883. Since then, the organization’s goal has been to decrease loneliness.

“The effects of the pandemic affected children, young people, families, and seniors, especially those who were already suffering,” Welfare Director Hanna Kari told The Click.

In Helsinkimissio, appeals for help increased by 30 percent in 2020. The biggest reason for contacting Helsinkimissio was the same for young and old people: loneliness.

For seniors, loneliness meant that there was nobody to talk to and nobody who would run errands for them. Older people were forced to stay at home during the lockdown.

For young people, loneliness causes anxiety about relationships and worrying about school and the future.

“We also noticed that violence among young people was getting very brutal. We saw that in the streets and the schools of Helsinki last spring and summer,” Kari said. “We also realized it here at the reception, kids wanted to talk about the things they have heard and seen,” Kari said. “We should be worried about our kids.”

Statistically, crimes committed by young people had been decreasing since 2012, according to a study made by the University of Helsinki. However, the pandemic has affected this as well. The amount of violent crimes has risen.

Jari Koski, a criminal inspector at the Helsinki Police Department, told MTV News this May that there had been a spike in the previous year in aggravated violent crimes committed by those under 18 years old. The police are also concerned about an increase in knives being carried by young people.

There have been several fatal stabbings committed by teenagers in the previous year. The media has also given these incidents a lot of attention.

The Pandemic Has Led to Another Epidemic

The United Nations and World Health Organization have also given a warning about a future mental-health epidemic.

António Guterres, the Secretary-General of the United Nations, said in 2020 that when the pandemic is finally gone, anxiety and depression will remain. The UN stated that mental-health issues should be treated immediately.

Sanni Lehtinen, a project manager of the collaboration of organizations The Finnish Partnership for Mental Health, thinks that mental-health problems have not been addressed well enough in Finland.

“According to an expert evaluation made by THL, mental-health services were overloaded even before the pandemic. Now the need for help has increased even more, but the services are not able to meet the demand,” Lehtinen said.

According to Kari and Lehtinen, the biggest problem in Finland when dealing with mental health is that the problem should be fixed before there is one. Now, the fix is coming too late.

“We know that the more quickly a person gets help for their problems, the smaller those problems grow,” Lehtinen said. “When this is considered, it is alarming to see how packed up all the mental health services are.”

Another problem is a lack of experts in the field. According to Lehtinen, a third of all the current psychotherapists are reaching retirement age. In addition, studying to be a psychotherapist costs between $20,000 and $70,000. It is one of the only fields in Finland that students have to pay for themselves.

Finland enjoys sunlight almost 24/7 in the summer. The winter on the other hand is dark because of the Polar Night. It is known as “Kaamos” in Finnish; the sun will not reappear until mid-January. [Credit: Sanna Voltti]

Finland’s Happiness Rank Feels Contradictory

The statistics about mental-health problems and suicide rates raise a question: Why is the happiest country in the world so depressed?

“I have been thinking about especially our elderly, are they really happy?” Kari wondered. “Even if people live longer and are generally healthy, it doesn’t guarantee mental wellbeing.”

On its website, the Word Happiness Report 2021 says that it mainly focused on the effects of the pandemic on people’s lives and how governments have handled the situation.

Finland has survived the pandemic reasonably well. The death toll has been moderate and the rate for vaccination for those over 12 years old is over 80 percent.

However, Lehtinen said that it is too early to tell how well Finland will handle the long-term effects of the pandemic.

“I’m sure that there is truth to it, that Finland is the happiest country. Still, it does feel contradictory. Finland measures well in the areas this particular study used, but did they observe everything?” Lehtinen told The Click. “There are so many effects we don’t see yet. We won’t know how we survived the pandemic until years from now.”

Finnish researcher Ilona Suojanen began studying happiness about 10 years ago while living in Finland. She was unhappy at her job and decided to write a master’s thesis about happiness in the workplace.

She completed her Ph.D. at the University of Edinburgh in 2017. That is when she officially became what she calls a “happyologist.”

According to Suojanen, different researchers are talking about “hedonistic moments,” a.k.a pleasure in life. Others are talking about “eudaimonic life,” meaning that the purpose of life is happiness. Some think that happiness is a mixture of those two. The most common question asked of her is about defining happiness.

There is no exact definition for happiness because everyone’s meaning is different, Suojanen said. For example, Finnish people appreciate individuality and peaceful life in general.

“It depends on what you are used to, or what is important for you,” she said. “A person can come from a very communal culture and fall in love with Finland because of the peace and quiet. Some might think that it is scary when there are no people around and only forest everywhere.”

Fall colors in Finland. [Credit: Sanna Voltti]

“We could shake things up a bit and have a different perspective. In some cultures, the question ‘How happy are you?’ is not even relevant,” she added.

One of the questions in the reports usually is: How satisfied are you with your life on a scale of 1 to 10?

“What does the scale even mean?” Suojanen said. “In a happiness conference, this Japanese researcher said that it is a silly question — the question should be: How happy are the people around you?”

Suojanen wonders why it is even important to rank countries based on their happiness. Cultures are different. Researchers are often surprised that Latin American countries do so well in the happiness reports. The explaining factor is usually strong relationships, which is quite opposite to Finland, where the culture is not so communal.

“Of course here in Finland, we are doing better than in Afghanistan, for example,” Suojanen said. “Or in Somalia, where there has been a civil war going on for I don’t even remember how long.”

According to Suojanen, measuring happiness is problematic because it increases the pressure to be happy.

“Pursuing happiness turns against itself at some point. Chasing happiness correlates with depression and loneliness,” she said. “Expectations are so high that you’re bound to be disappointed.”

Humankind has a need to measure things, but measuring the happiness of countries is not relevant, Suojanen said. The experience of happiness is unique for everyone.

“Each one of us has a certain level of our own happiness. The society surrounding us affects the idea of what happiness is. However, we all have our own definitions. If you want to be happy you should take a moment and ask yourself: What does happiness mean to me?”