Flagler Village in Fort Lauderdale used to be home to drugs, murder, and prostitution but now finds itself home to new businesses, working professionals, and rapid development.

( FORT LAUDERDALE, Fla. ) — If you take a minute, sit back, close your eyes and think of Fort Lauderdale, what images come to mind?

I’d hazard a guess that it’s a mix of bright sunshine, palm trees, sandy beaches—and spring break debauchery.

You’re likely not thinking of drugs, prostitution, gangland killings, and abject poverty. But that is exactly what part of Fort Lauderdale had for much of the 1980s and 1990s, and the place where most of it happened or could be expected to happen was in Flagler Village—then called Flagler Heights.

Just ask Mike Ferber about that. He bought a house in Flagler Heights for $38,000 cash in 1986 and still lives there to this day, doing his weekly sweeping of leaves from the original walkway in jeans and an oversize long-sleeve shirt. Ferber has seen the neighborhood at its absolute worst, at the height of the crack cocaine epidemic that swept America, for which Fort Lauderdale had a direct pipeline via I-95 from Miami. For him, that meant trying to mind his own business in a troubled neighborhood while living across the street from a man whom he claims was a prominent drug dealer at that time. Thankfully for him, the two didn’t cross paths that often, but when they did see one another, it was usually confined to a simple head nod and then onto other things.

“I wanted him to know that it doesn’t matter to me how a man makes his living. You’re concerned about who I am. I’m not about to call anybody. I mind my own business.”

Video: Flagler Village Revitalization

‘The tracks were the dividing line between white and Black’

A crime-ridden neighborhood was not what Henry Flagler envisioned when he built the Florida East Coast (FEC) Railroad in the late 1890s. It certainly wasn’t a neighborhood he’d have wanted his name attached to a century later. Up until the railroad came, South Florida was just a few settlements, largely unpopulated after the Second Seminole War in 1842.

The railroad brought a massive influx of people and business to Fort Lauderdale in the 1920s. By 1940, the population was just shy of 18,000 people. By the mid-1980s, it had ballooned to more than 150,000.

With that boom, came infrastructure and affluent people making developmental decisions, including segregating the city.

The FEC line, which initially divided east and west, was now the divider between white and Black, and the affluent and impoverished.

Census data from 1970 -1990 shows the poverty rate among Black families in what was Flagler Heights skyrocketing from barely measurable to as high as 63%. Over the same period, the poverty rate among white families peaked at 12%.

There are still parts of Flagler Village that are hanging on despite apartment development all around them. [Credit: Jeremy St. Louis]

Except in the middle, in Flagler Village, which became the haven for drugs, prostitution, and violence during the mid-1980s crack cocaine epidemic.

“Flagler became the inter-zone, the place in the middle. There was a tremendous amount of it … it was out of control,” said Ferber, staring off into the distance recalling those days.

Eventually, the city decided to step in. Arrests were made, water and electricity cut off to known drug houses and everything boarded up.

“That was definitive, but that’s how out of control it was,” Ferber said.

“Flagler Village was ignored for a long time”

For guys like Ferber and developers like Charlie Ladd, they saw the bad but they also saw the potential – eventually. While the city was focused on improving areas downtown and along the waterfront, Ferber, Ladd, and other developers bought lots in Flagler and simply waited.

Ladd, 61, owns Barron Development and has been in the area since he was 23.

“I wasn’t as focused on Flagler initially,” he said, from behind his desk at his Fort Lauderdale office on a Zoom call with a reporter.

Neither was Jamie Sturgis, 31, who owns Native Realty. Sturgis grew up in Fort Lauderdale and also knows the history.

“This (Flagler Village) was always kind of a depressed, blighted area. Historically, it was a lot of workforce housing, which became a gateway to prostitution and drugs and all sorts of things, unfortunately.”

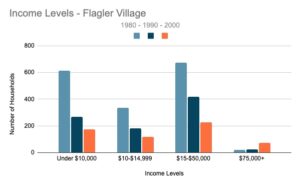

Based on U.S. Census household income data since the 1980s, close to 1300 households were earning less than $50,000 per year in 1980 and almost half that earning below $10,000 per year.

U.S. Census data on Household Income in Flagler Heights/Village.

Unlike Ladd though, Sturgis is not a developer, he is more into the retail aspect of the neighborhood and has helped bring in some unique new businesses to the area, including his own. Native Realty has its headquarters on the northern end of Flagler Village.

In fact, Native’s offices are not far from Glitch Bar, one of those aforementioned unique businesses. Owner Dwight Slamp converted two garages into the retro 80s arcade five years ago. Slamp also wasn’t even looking at Flagler Village as a location.

“I kind of got stuck with this and I had to make the best of it,” he says. “When we signed the lease, there were hookers down the street. That was almost five years ago so the neighborhood has definitely changed.”

But redevelopment hasn’t been easy. Remaking a neighborhood is a slow process, and there is concern over the cultural aspect that is being lost. That’s where people like Grace Kewl-Durfey come in. Kewl-Durfey is director of community engagement for the Broward Cultural Division. She has lived in the area since 1982 and while her offices are outside the area, she knows the challenges Flagler Village and other areas have faced.

“There’s a lot of negative history here,” she says. “And racism is rampant still.”

Thaddeus Bethel agrees with that. He bought a small house in Flagler back in 2006 and has invested his time and energy into making it stand out. And it does. His front yard is filled with elaborate vegetation and classic white patio furniture for a warm, Florida feel. From that yard, Bethel has witnessed the neighborhood changes first-hand. As a Black man, he’s also witnessed and been subject to racism—mostly with law enforcement.

“I would say I had a lot of bad experiences with officers,” he recalls.

Recounting those experiences as he sat in his ornate front yard, Bethel says that’s par for the course in this area of town, given its history. As for the culture in the area, he readily admits things have definitely changed.

“When I first came in, there were more Blacks in the neighborhood than there are now, now it is more mixed than it is Blacks. And again, I don’t have a problem with anybody or anything, you know … you’re nice to me, I’m nice to you. That’s my culture.”

And that is part of what Kewl-Durfey wants to save. The topic animates her, and she says one of the biggest challenges is with developers, who come in and execute their vision with little thought for what history might need preservation.

“It’s messy work,” she says.

For Ladd, he recognizes that traditional Black neighborhoods do need preservation but not in Flagler Village.

“Flagler never had that kind of character. It was a hodgepodge. You had car dealerships and parking lots.”

Lee-Ann Barber, president of the Flagler Village Civic Association, is quick to counter that by pointing out that culture and character are not just architectural, they are woven into the fabric through the people who inhabit—and have inhabited—the dwellings. She bristles at the notion that the area lacks character and culture.

“Every place has culture. It’s your choice whether or not you choose to recognize it,” she says.

She knows most of the developers who want to capitalize on the area through her involvement with the Community Redevelopment Association. She is not opposed to redevelopment but says it’s not happening in the right way.

“What you have is a tremendous group of people who cannot afford a place to live, period.”

She points to her own block on NE 1st Avenue as an example. The complex next door to her 86-year old home has two-bedroom apartments priced at $1,250 a month. Across the street— only 100 feet from her driveway—a two-bedroom rental at a new building goes for $3,000 a month.

‘Plenty more to come’

Small pockets of the neighborhood are hanging on. According to Ladd, it may not be for much longer.

“There’s one guy there that owns six lots and he just put them up for sale. Another guy owns four, and there are two or three sellers that are ready to sell.”

Barber points to her front door and says she knows she’ll hear that knock someday soon, and she’s not sure if she should refuse.

“I don’t know if I should keep it as an old historic house. Keep it here as this little reminder that this is how Florida used to be, you know, or let it go.”

Both Bethel and Ferber have also had offers.

No matter where development goes, or whether or not those who have been here the longest stay or move away, it’s clear that Flagler Village is changing. Gone are the days when it was an ignored part of town, referred to as a “slum” and filled with crime, which is what makes Flagler Village a tremendous success story for Fort Lauderdale.

“Unless you’ve been here since the very beginning, I don’t think you have any comprehension of what’s really happening here,” said Ladd.

“It’s an opportunity to take something that was blighted and neglected and try to do something better with it, and, in turn, help the city I loved growing up in,” adds Sturgis.

While residents like Barber and Bethel can agree with the sentiment, they see the loss of culture, a loss Barber reluctantly laments is inevitable.

Despite that, when you can walk down most blocks in the Village and see ‘Coming Soon’ signs for hair & nail salons, a bakery, coffee house, bar, and various little shops, one can’t deny that Flagler Village isn’t in a better place now than it has been in a very long time.

If he were around to see it today, it’s hard to imagine Henry Flagler disagreeing.