NASSAU, The Bahamas – It has been three months since Hurricane Dorian, a Category 5 storm, destroyed parts of The Bahamas’ northernmost islands, Abaco and Grand Bahama. Ninety miles away, in the capital of Nassau, Pilgrim Baptist Temple opened its doors to over one hundred evacuees. But, if you were to pass the church today, there would be no indication that hurricane survivors resided there just three months ago.

“Some (of the evacuees) were very friendly,” said one church neighbor, Ms. Gray. “It was fun! The children running up and down. The neighborhood gone right back, dead.”

Rooms that served as doctor’s quarters at the church after the hurricane have since been restocked with Holy Communion; pillows and blankets have been stored; tables and chairs and even paintings for an annual neighborhood art show now fill the room that was once lined with mattresses and people; people who remain displaced, as they have no homes or familiarity to return to, especially now during the holiday season.

Dorian Arrives

Hurricane Dorian made landfall on Elbow Cay, Abaco, Sunday, September 1, with winds of up to 185mph, gusts of over 220mph and storm surges in excess of 20 feet. The strongest storm to ever hit The Bahamas, Dorian left 70 people dead and thousands both missing and displaced in Abaco, its cays and eastern Grand Bahama.

“We were expecting the hurricane,” said Bahamian shelter resident and Grand Bahama native, who prefers to be identified by his surname, Bain. “[A]ll arrows were pointing that it was coming, but no one expected it to be that serious. [T]his one was quite different.”

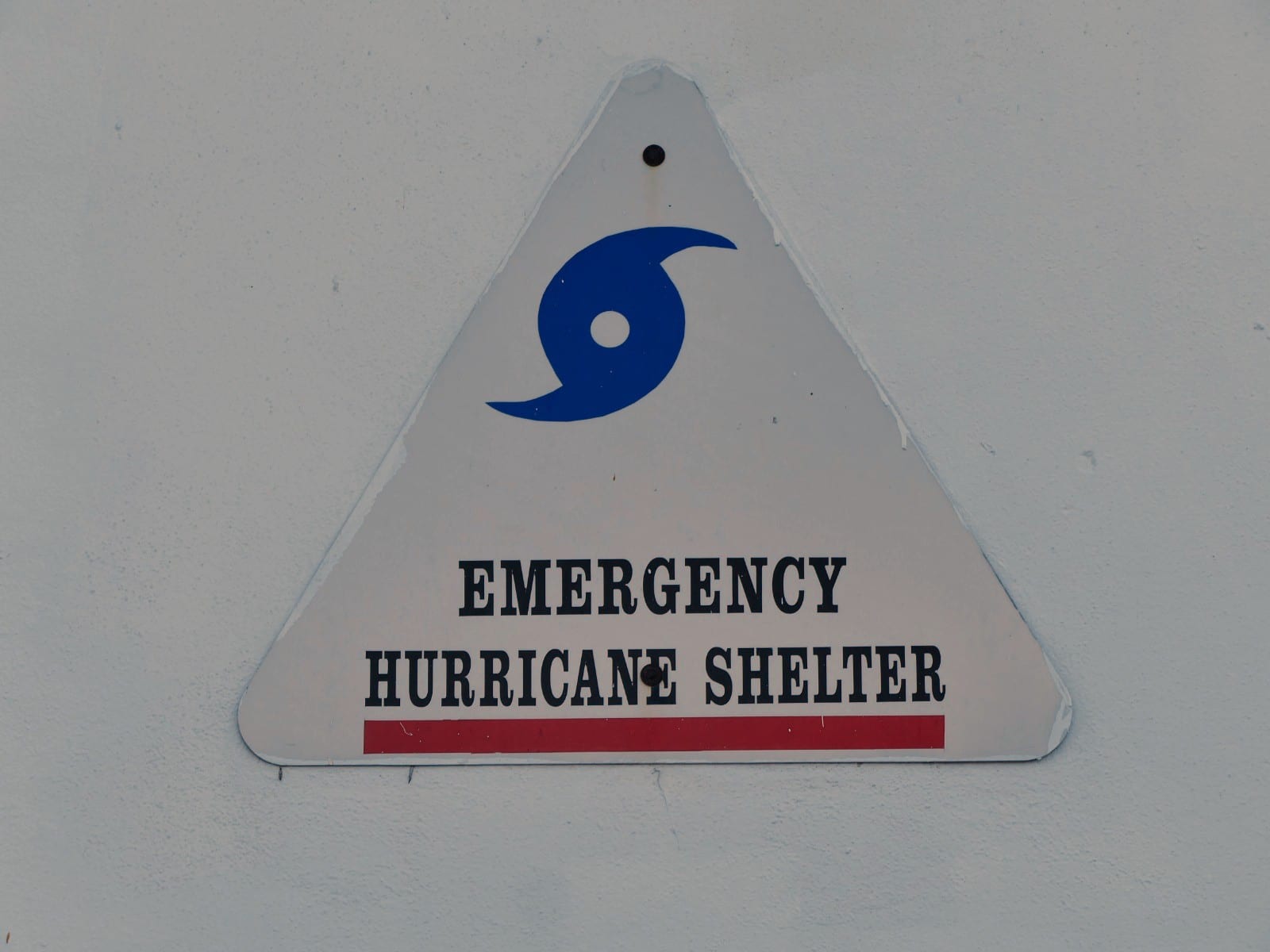

Located on St. James Road in a quiet and tight-knit community called Kemp Road, the church faces a large open lot, surrounded by houses where children gather to play in straw huts that extend from one end to the other. A sign on the southeastern wall reads, “Emergency Hurricane Shelter,” which leads into a clean and spacious hall that comfortably holds 150 people.

When the all-clear was given, thousands of evacuees left the only home they knew, in search of safer land, with the help of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and each other.

Shelter resident, Nathaniel, uses his cell phone in the church’s courtyard. [Credit: Nasia Colebrooke]

Hundreds sailed to South Florida, a few settled on nearby islands, some opted to stay, but most found themselves on the island of New Providence, home to the nation’s capital, Nassau.

Seeking Shelter

Sandra Fox. [Credit: Kohfé Miller]

Marsh Harbour suffered a similar fate in 1926. “[O]fficials, journalists and townsfolk alike had proclaimed it the end of days,” according to The Nassau Guardian. Fast forward to nearly a century later, and the island is suffering the same fate with Hurricane Dorian. In fact, the City of Freeport, Grand Bahama’s commercial hub, has still not fully recovered from the damage left behind by Hurricane Matthew in 2016, a Category 4 storm.

For shelter residents like Nathaniel and Bain, Pilgrim Baptist was a source of refuge and brought back a sense of normalcy into their lives.

“We threw a welcome party to make them feel good and feel at home and many of them attended our church service that morning,” said Fox. “We had droves and droves of food coming in every day, [to] a point where I appointed a few days for members to use the kitchen to cook their own meals.”

Shelter residents, sometimes, even treated neighborhood friends, like Ms. Gray, to extra food.

“[I]f it was apple, cake, they would give it out. We were friends,” shared Ms. Gray.

One resident who enjoyed his time at the shelter is 10-year-old Taurus Saintvil of now-obliterated Abaco shantytown, The Mudd. Up to the time of being interviewed, Taurus was not enrolled in school and was still a resident of the shelter along with his mother, stepfather, younger brother and younger sister.

“I like the shelter because we get to sleep anytime, charge our phone all day, go upstairs; it’s a nice view,” said Taurus, who admits that he misses home. “My favorite thing to do is play dominoes.”

Presiding pastor, Leroy Nathaniel Major, welcomed residents to his home for a pool day and took them to watch a regional soccer game at the Thomas A. Robinson National Stadium, where they also enjoyed a parade.

“He [pastor Major] wanted them to stay but he didn’t know [their legal status],” shared Benson, a neighbor. “It was a tough decision.”

Shelter residents were also treated to regular doctor’s visits. According to Fox, local government doctors and nurses as well as volunteers from global health and humanitarian relief organization, Project HOPE, visited the shelter everyday – which was comprised of 80% Haitians and 20% Bahamians, with 95% from Abaco and 5% from Grand Bahama. There was even a Haitian Creole interpreter to make the Haitian residents feel more comfortable.

However, as shelter occupancy was decreasing, the government ordered a mass deactivation on Friday, 11 October, providing residents with four choices. According to Fox, they could either: stay at the Kendal G. L. Isaacs Gymnasium, the largest and most central shelter; with family or friends; in a hotel or a motel; or travel back home or out of the country – the latter two to be financially covered by the Department of Social Services. These options, however, leave Haitian residents, specifically, with no place to call home, as they do not have the resources (money, family, friends) that Bahamians do.

“When I reach to this shelter, I gone into a serious, serious depression. I didn’t know what to think,” said Nathaniel. “I watch my car fly ‘cross the road! [W]hen that was over, I was so happy! I say ‘Thank God I ain’ die,’ ‘cause for a minute there I say, ‘This is it! This is it!”

Fox, who is grateful to have been a source of support during such a tragic time, admitted that shelters “should have more privacy” in the case of future emergencies. Still, she and Gray both miss the residents and “hope[s] they are all well.”

Staying Connected

Today, the Kemp Road community has remained connected through participating in a luncheon and boat cruise with senior citizens; hosting their annual Thanksgiving service (distributing over 100 bags of groceries to church members); and hosting a Christmas party for neighborhood children. However, many survivors won’t be in such high spirits this yuletide season, as the government has plans to evict remaining shelter residents and house them in 110 domes that are scheduled to be erected on Abaco by Christmas Day; domes for which the government has yet to decide will be free of charge or not.

Nevertheless, the “big, white church down the hill,” as one neighborhood resident describes it, that stood, if only for a moment, as a pillar of strength and protection for a group of people that survived the unimaginable, still stands today as a pillar of spiritual, emotional, physical and communal strength for anyone who walks through its doors.

- A view of St. James Road (north). [Credit: Kohfé Miller]

- A view of St. James Road. [Credit: Kohfé Miller]

- Emergency Hurricane Shelter sign. [Credit: Nasia Colbrooke]

- What was once a shelter is now being used as a meeting space. [Credit: Nasia Colbrooke]

- One of two rooms that were used as a doctor’s and nurse’s station. It is now restocked with church items, but a black folding/privacy screen still remains. [Credit: Nasia Colbrooke]

- The second room that was used as a doctor’s and nurse’s station. [Credit: Nasia Colbrooke]

- The frame of a cot still lies upstairs in the corner of a room where a missionary slept who got caught in Hurricane Dorian. [Credit: Nasia Colbrooke]

- An interior view of the sanctuary at Pilgrim Baptist Temple. [Credit: Nasia Colbrooke]

- The courtyard that separates the shelter on the left and the sanctuary on the right. Many of the residents also enjoyed playing Dominoes here. [Credit: Nasia Colbrooke]

- A child’s toy and a box of hygiene kits are left behind after the shelter was deactivated on Friday October 11. [Credit: Nasia Colebrooke]

- Bags filled with shelter supplies are placed into the corridor outside of what was once the doctor’s and nurse’s stations. [Credit: Nasia Colbrooke]

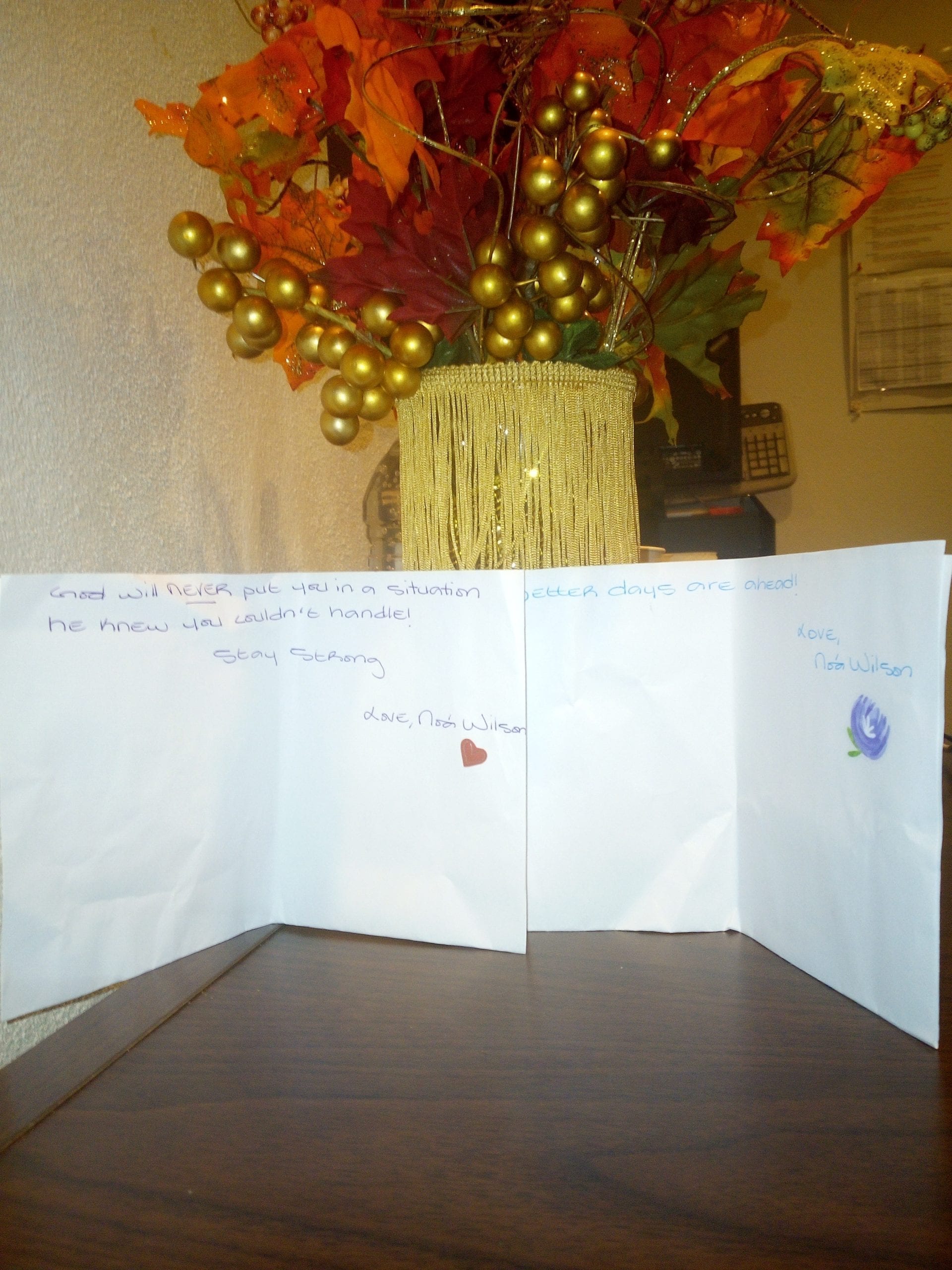

- Handwritten notes of love and encouragement to shelter residents from Coca-Cola Puerto Rico Bottlers (CCPRB). Volunteers from the CCPRB understood exactly what residents were going through, after having endured Hurricane Maria in 2017. [Credit: Nasia Colbrooke]

- Neighborhood children play near the straw huts in the church’s parking lot across the street. [Credit: Nasia Colbrooke]