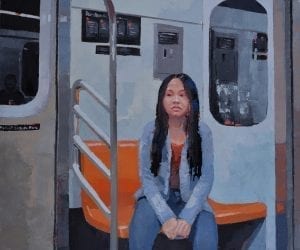

“Her Space” by Krista Townsend. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of the artist.

Charlottesville, the beloved home of Thomas Jefferson, has a new and unwelcome reputation. Since August 12, 2017, the city’s name has become shorthand for a hate-filled rally and deadly terrorist attack by white supremacists. For local artists, whose work played a part in shaping the town’s relaxed hipster persona, the aftermath of A12, as it is known, has caused them to consider whether artists can, and even should, save the city’s soul.

“We used to pride ourselves as this idyllic city of culture and history,” said Sam Bush, a music minister at Christ Episcopal Church and the director of multipurpose artspace The Garage. “Turns out we’re just as screwed up as any other city.”

Charlottesville’s artists are talented and passionate. They were among the first to craft strong rebuttals to the violence of A12, with exhibitions and public art that railed against hate and celebrated the city’s activists. But two years later, they remain conflicted over the role art can play in shaping their community’s future. While some have abandoned their neutral work for a politicized practice, others believe the problem of prejudice is too big to tackle.

“I tend to recoil whenever art is used as a platform for any kind of message,” said Bush. “The inspired medium of art is that it transcends the labels we use on each other.”

As the proprietor of The Garage, a repurposed car garage that uses a nearby hill as seating for performances, Bush maintains that providing a place for people to grieve and commiserate has been more important than using the tragedy to say something about himself.

“In the aftermath of August 12, it felt like everyone was making a statement. Every musician just wanted to say, ‘By the way, I’m against Nazis,’” he said. “It just so often turns into self-congratulatory promotion of, like, ‘Look at me, I’m a good person. I’m not the problem.’”

Top: Artists contribute to the memorial on Heather Heyer Way.

Bottom: The Robert E. Lee statue in October, surrounded by netting and marked with “1619.”

Bush’s sentiments split from those of other gallerists in Charlottesville. At venues such as the Bridge Progressive Arts Initiative and McGuffey Art Center, activist art has taken a higher priority since A12. But it hasn’t always gone over well. At McGuffey, an artist-run co-op known for workshops and classes, the October 2017 show “All Rise” featured confrontational installations—such as a set of mirrors labeled “for whites only,” branding onlookers as complicit in systemic racism. The long-planned show had shifted focus after the attack, a move that operations manager Nina Burke said was controversial even among staff.

The fact that local artists are divided over how to respond to A12 comes as no surprise to Grace Aheron, a writer and activist who helped organize counter-protests that very weekend. After all, the effects of the attack are still fresh. The neo-Nazi who killed Heather Heyer received a life sentence in April, and many victims are still recovering. Aheron interprets artists’ reticence to make a statement as imposter syndrome—the feeling that if they weren’t there, they can’t say anything.

“I was as close as you could be, in a lot of ways, to the [counter-protest] organizing that was happening,” said Aheron, who today serves on the national leadership team for Showing Up for Racial Justice, a network aiming to undermine white supremacy. “And I still feel like I don’t have a right to speak for people or make meaning in a way that is broad and generalized—to say ‘This is Charlottesville.’”

Aheron had pushed to mobilize the art community before the Ku Klux Klan rally that preceded A12. She asked city residents to help her fold a thousand paper cranes to spread in the parks, each representing individual commitments to dismantling white supremacy.

“There weren’t a lot of people [in Charlottesville] interested in protest art,” said Aheron, who now lives in Philadelphia. Recognizing there was a void to fill, she focused on producing poster campaigns with SURJ and other projects to bring awareness to local problems.

By contrast, artist Megan Read believes in a more individualistic role for creators.

“I don’t think that we have any obligation to take a stance on politics,” she said. “All I have to say is my experience. I don’t feel like I have the authority to make bigger statements other than what I know.”

“Faith” by Megan Read. Oil on linen. Courtesy of the artist.

A full-time painter of two years, Read’s hyper-realistic nude self-portraits contrast the natural contour of the human body with the artificiality of athletic wear. She uses herself or still-life arrangements as models, but acknowledges that keeping her practice personal is difficult. Just painting other people, as she’s considered, might denote a social stance.

“Once I start doing that,” said Read, “I am actually making statements on race and body image and all these different things by choosing to represent certain people.”

One local artist, however, found liberation in painting others.

“I wasn’t even here,” said Krista Townsend about A12. “I was on my way to Canada.”

Townshend, at that time a landscape painter, was in the airport watching news broadcasts about the violence erupting in her hometown.

“One of my best friends was there and was trying to call me while I was on the plane,” she said. “And she was hiding in an alleyway door, terrified, just trying to get in touch with somebody that she knew might be around. And I wasn’t there for her.”

By the following summer, Townsend had reached the limits of what she could express in landscape painting. As she was listening to the confirmation hearings for Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh in her studio, she became so frustrated that she threw aside her landscapes and began painting a 6-by-3-foot portrait of her friend in a jiu jitsu gi, a martial arts uniform.

“It felt so good. I wasn’t painting for a gallery, I wasn’t painting for a commission,” she said. “I was just painting to relieve the pent-up stress of listening to Christine Blasey Ford pouring her heart out in front of Congress.”

“Finding Her Way” by Krista Townshend. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of the artist.

That first portrait led to a yearlong series of figural works, titled “The Art of Being a Hero.” Drawing on her prior experience as a medical illustrator, the artist captures the dignity and perseverance of Charlottesville women, in both confrontational and vulnerable positions. Her subjects range from A12 activists to a clarinet player to her stepdaughter alone on the New York subway.

While the contrasting views of local artists reflects a care and consideration for their community, the state of the city’s public art represents the difficult road to reconciliation that Charlottesville faces. In September, the Charlottesville Circuit Court ruled the city could not remove the Confederate monument of Robert E. Lee. The offending statue is a protected “war memorial” under Virginia law, Judge Richard E. Moore found.

It’s a significant blow to a city that has made great strides since A12. Nikuyah Walker, the city’s first black, female mayor, was elected just months after the rally on a campaign claiming local Democrats had ignored the city’s racial divide. And the superintendent of schools for Albemarle County—the region surrounding Charlottesville—has moved to ban racist symbols from the student dress code.

But the protection of the Lee statue is a stubborn reminder that change in Charlottesville will come slowly. The events of the “Summer of Hate,” as some local outlets call it, laid bare a deep-seated history of inequity in the city—and across America. Which role artists will play in its future remains a work in progress.