PORT JEFFERSON, N.Y. – One day last September, Ana Hozyainova stared at an empty plot of land that, just hours earlier, had been part of the last undisturbed forest in the Village of Port Jefferson, a small harbor town on the shores of the Long Island Sound. After the Suffolk County Supreme Court denied an emergency stay on the clearing, bulldozers had taken down the trees.

The clearing replaced roughly two acres of mature trees in the 37-acre forest to make room for additional parking spaces at Mather Hospital — a necessary part of an expansion project, according to the hospital. More parking is needed for staff and patients as part of a multi-phase $78.7 million plan to grow emergency room services.

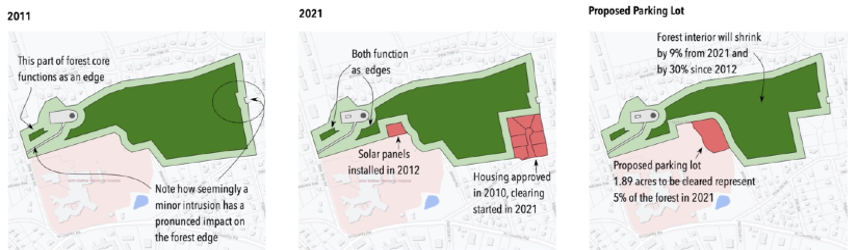

The forest, which has no name or designation as protected habitat, stretches over the properties of three owners. This last cut into the acreage owned by Mather Hospital is one of several intrusions into the forest edge and has reduced its interior by about 30% over the past decade.

“I don’t think people would consider this small clearing a big deal,” Hozyainova said. “It’s when you contextualize it to years of land loss.”

Most people think modern-day deforestation happens in faraway places, like the Amazon rainforest—not in their neighborhoods. Yet, in U.S. cities, 36 million trees are cut down annually, and 167,000 acres are replaced by concrete and asphalt, according to a 2019 report by scientists at the Department of Agriculture. Forests are critical for human health. They keep communities cooler, improve air and water quality, control rainfall and water runoff, and reduce noise pollution.

Hozyainova, 42, a social worker and amateur naturalist, is worried that the succession of cuts into the forest’s boundaries would compromise its health. “A forest is not two or three trees stuck together — it is an entire system that needs a minimum space to function,” she said. “The smaller that space becomes, the less it can support diversity, and it starts to die out.”

“The forested area at Mather Hospital represents one of the more extensive areas of forest habitat in this part of Long Island and is a unique, diverse ecosystem — and a source of biodiversity in the surrounding suburban area,” said Jessica Gurevitch, professor of ecology and evolution at Stony Brook University.

For months, Hozyainova and other residents fought to persuade the village planning board to work with the hospital on finding an alternative parking solution, such as erecting a parking structure on already asphalted land. But the village decided to greenlight the project in June over the objections of many locals. In August, Hozyainova and another Port Jefferson resident, Holly Fils-Aime, filed a lawsuit against the hospital and the village planning board. The lawsuit challenged the State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQR) determination, the procedural process set in place by New York State law to identify possible environmental harm during the planning stage of a development project.

Hozyainova and Fils-Aimes’ legal complaint alleged that the planning board did not adequately assess the impact on the whole forest in determining that the parking lot expansion posed no significant environmental harm. They wanted the decision reversed.

“I looked into the mechanisms to enforce the law. There are none,” Hozyainova said. Once a planning board makes a final decision, there is no recourse other than to sue, she explained.

Hozyainova wanted to work within the system to protect the forest. Still, she discovered that the SEQR process is mired in a web of administrative protocols and turgid town building codes. Participating in the process requires constant attention to timelines and comment deadlines.

For small municipalities like Port Jefferson, the quality of the SEQR process depends on whatever expertise a planning board member brings to the appointment. “The reviewer is not expected to be an expert in environmental analysis,” according to the SEQR handbook. Planning boards are responsible for reviewing the accuracy of the SEQR application submitted by a developer. In Port Jefferson, board members are unpaid volunteers recommended to the village trustees by the mayor, according to Village Mayor Margot Garant.

Several months after the clearing, Hozyainova gave me a tour of the remaining undisturbed forest. At the trailhead are a chain-link fence and construction debris. We walked instead along the forest edge, behind a solar panel array that replaced another swath of forest edge in 2012 by Mather Hospital.

The forest, for years, had been open access for residents to enjoy the trails. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the woods were “the place where we could be and not be afraid, the untouched space,” said Hozyainova.

When she learned about the proposed parking lot expansion in December 2021 over coffee with a friend, she remembered why she had moved to Port Jefferson in the first place. “We wanted to live in a green place, both in appearance and for its commitment to maintaining natural habitats.” She lives within walking distance of the forest, which is “teeming with life,” she says. Stony Brook’s Gurevitch, in her written expert testimony for the lawsuit, said that more than 40 bird species, nearly 20 mammals, the only North American marsupial (opossums), multiple species of reptiles, and many species of insects, such as butterflies, native bumblebees and solitary bees all rely on the forest.

Trailhead removed with the forest clearing. (Courtesy of Anna Hozyainova, September 2022)

Port Jefferson, a harbor enclave of about 8,000 residents, is mainly known as a transportation hub for the Long Island to Connecticut ferry system and for its proximity to great beaches on the Long Island Sound. The village harbor is also the site of a LIPA (Long Island Power Authority) power plant. For decades, it has supplemented the tax base, allowing residents to enjoy some of the lowest taxes in the region, according to Garant, the mayor.

The village has been under increasing pressure to diversify its tax base in recent years. The LIPA power authority has challenged its tax bill in court as the plant’s technology and infrastructure have become obsolete. With this pressure has come an uptick in the construction of multi–family housing and further commercial development of the village. The development promises rejuvenation while helping to counter the loss of tax revenue. “It is vitally important to stabilize the tax base by preserving our commercial business districts and home values,” said Garant. “This will help to offset the loss of revenue from LIPA.”

However, this promise has brought new pressures on the environment in the form of land fragmentation in the village and what little is left of intact, forested areas on Long Island.

Gurevitch characterizes the fragmentation of the forested area crossing the Mather Hospital property as environmental harm, regardless of the size of the cut. “The natural habitat on Long Island is rapidly disappearing,” she says.

Graphic depictions of edge clearing over time in the forested area are part of Gurevitch’s lawsuit testimony. “This forest’s interior has shrunk 30% over the last decade,” Gurevitch said. (Courtesy of Jessica Gurevitch, August 2022)

SEQR is one of many state laws designed in the 1970s in response to the general awakening in the country that human development activities can harm the environment. SEQR legislation dates to 1978 in the wake of NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act), the 1969 federal law that introduced the idea of the environmental impact statement.

Identifying cumulative environmental harms of several unrelated projects over long periods, as seen with the forested area at Mather, is a noticeable weakness in the SEQR legislation.

“Cumulative impacts are a challenge. Some people would say that they get overlooked or not given sufficient weight,” said Edward McTiernan, former deputy commissioner and general counsel at the New York State Department of Conservation.

Some people might be surprised to learn that the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) has a limited role in overseeing SEQR. “The DEC puts out education. They support the rest of the government and enable planning boards or other public bodies to make informed decisions,” McTiernan said.

By the planning board’s acknowledgment, the “project generated a substantial amount of public criticism,” according to the final SEQR assessment issued by the board in June. Gil Anderson, a civil engineer and longtime planning board member, focused on what he felt were the most critical issues of the project as a whole: flooding, water runoff, and traffic. “We were satisfied that the SEQR process was completed,” Anderson said.

Mather Hospital “thoroughly evaluated potential impacts of the project upon environmental resources in coordination with the Village of Port Jefferson” as part of the SEQR process, adding that “the hospital has committed $25,000 to the Village of Port Jefferson to plant trees within the Village,” according to a statement. Anderson added that he felt it “was a pretty fair trade.”

Gurevich believes the new planting proposed by Mather “not only fails to compensate for the clearing but will further undermine the forest,” adding that “the proposed clearing will result in cumulative destruction of nearly a third of the ecosystem since 2011.”

“Cumulative impacts are a challenge. Some people would say that they get overlooked or not given sufficient weight,” said Edward McTiernan, former deputy commissioner and general counsel at the New York State Department of Conservation. The forest edge was cleared for solar panels in 2012. (Photograph: L. Hallarman, November 2022)

Legal experts Michael Gerrard and McTiernan, who have been following SEQR court petitions for the New York Law Journal for 32 years, point out in their 2022 case review that most of the time, plaintiffs seeking a reversal of a negative determination by the courts lose.

Hozyainova’s hope now is that she can work to save the remaining forest. She recently restarted the Port Jefferson Civic Association to counter what she feels is an imbalance in the village’s approach to developing the open spaces that are left.

“We need to find balance because we need construction,” she said, but “in a much less damaging way than it is being done now. We all now have that burden.”

Watch an expert drill down the basics of SEQR below :