(NEW YORK) — Washington Square Park in the afternoons is a beautiful maze of intersections. The park bustles with students from the nearby NYU campus milling about between classes. A regular flux of bikers with backpacks stuffed with food deliveries zip through the surrounding side streets while near the center fountain, a protest group gathers to hand out pamphlets, chanting rallying campaign calls behind half-worn masks. Scattered police take turns patrolling the park entrances. From an epidemiologist’s perspective, it’s a perfect petri dish.

In a few days, the park will be packed with revelers celebrating the presidential election victory of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, the air echoing with cheers and shouts throughout the day as streams of people pass through from different neighborhoods hopping between celebrations to celebrate the historic moment. Taxis, Ubers, and ambulances alike will be busy for the next few days.

Washington Square Park alit with election celebrations bringing together the city, though perhaps not in the safest of times. [Credit : Katherina Nguyen]

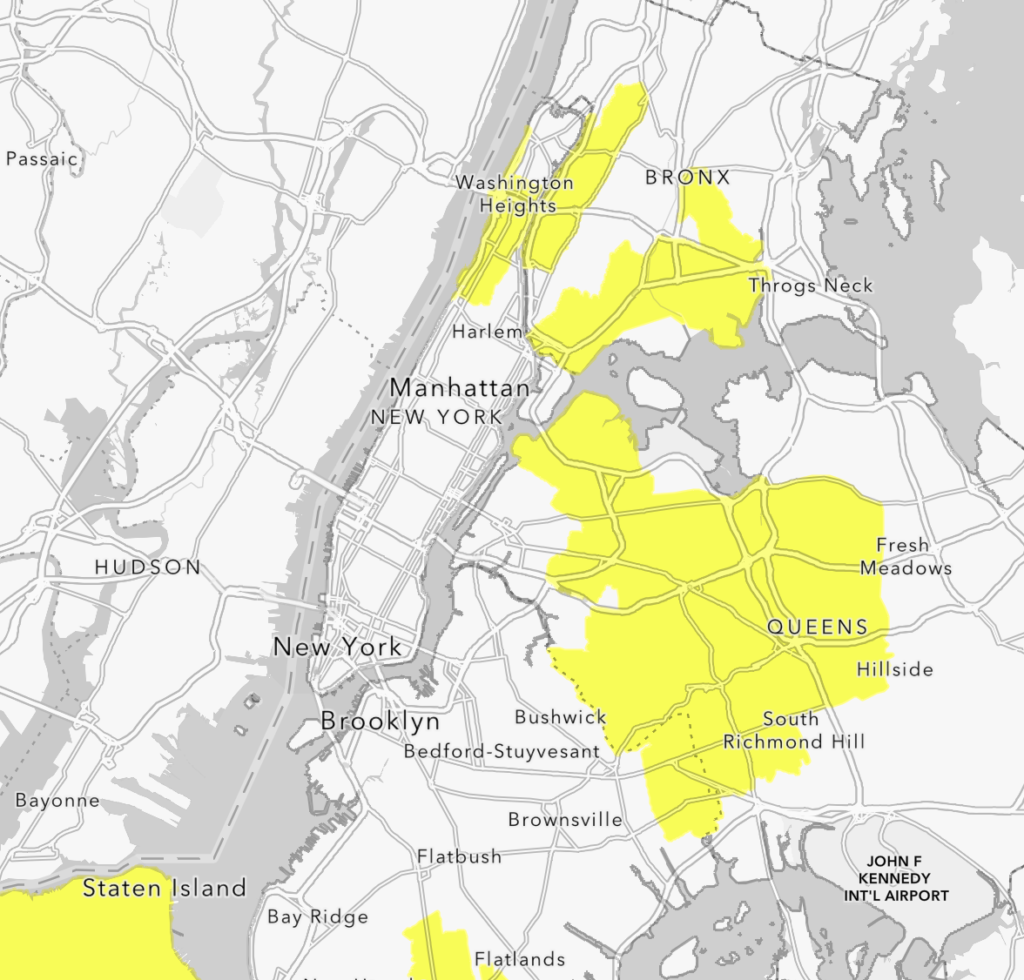

Clustering classifications as of 11.23, regions that remain in the yellow classification have greater than 3% rolling 7-day positivity average and no decrease in hospitalizations. [Credit : NY OpenGov ]

“It’s not working because people move around, they don’t stay in their area. If in principle people stayed in their area, that would work, but that doesn’t happen,” he shared.

New York City’s current containment strategies target neighborhoods at risk but miss out on movement and cross-exposure risks between neighborhoods, like those faced by essential worker communities in emergency health services and rideshare sectors.

While much of the conversation around COVID-19 has centered around the effectiveness and challenges of the enforced lockdown policies across US cities, less attention is given to the science of movement—which populations are traveling from one place to another and how that mobility impacts the spread and containment of the disease.

In Service of a Restless City

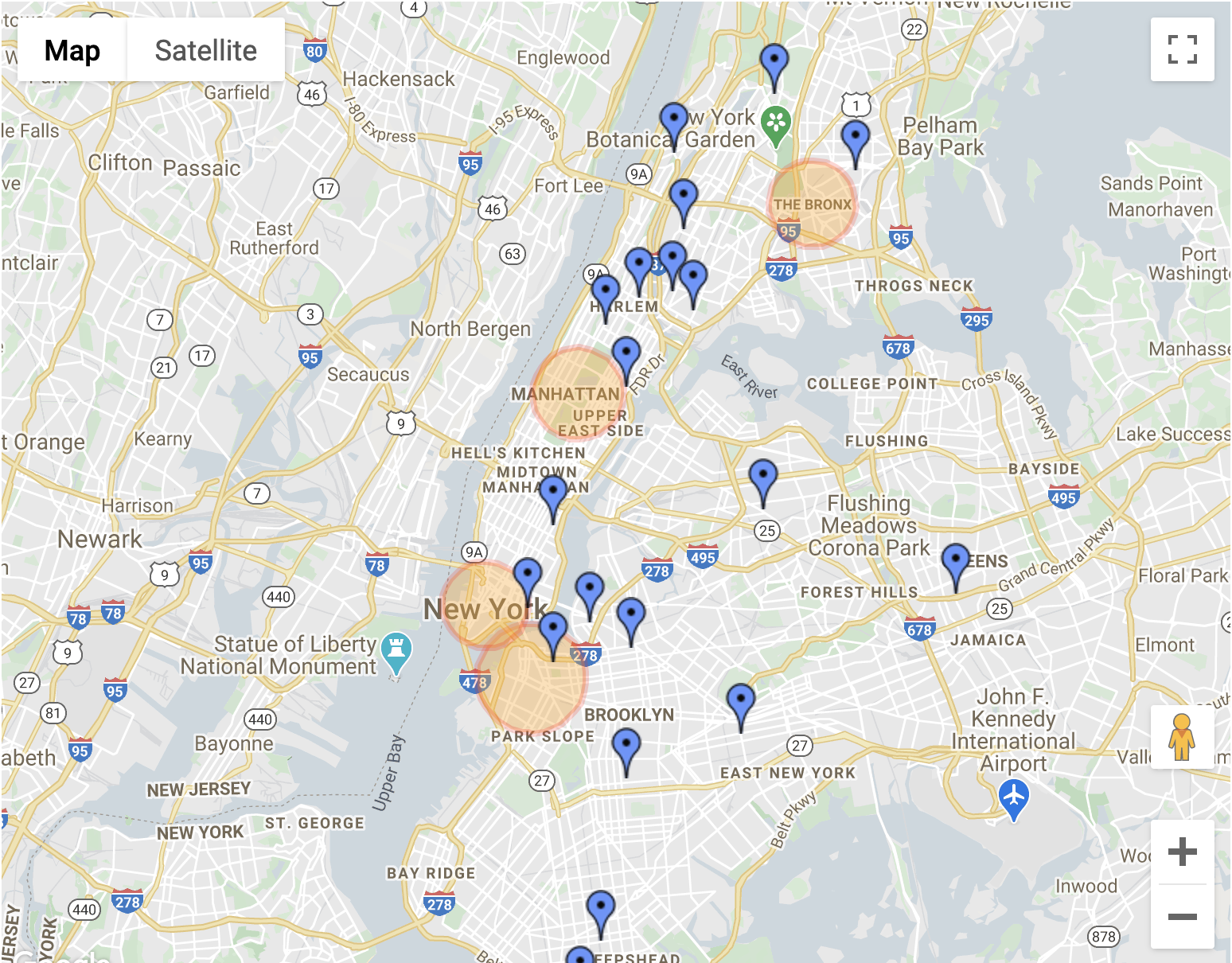

This summer New York City was the site of many charged civic protests sparked by the May death of George Floyd at the hands of police in Minneapolis. The fall in turn brought a spike in demonstrations related to the national election. These events left their mark on the city with marching routes crossing through neighborhoods, adding to the challenge of tracing and containing the virus within micro-clusters. While most gatherings were peaceful, they were events that brought together large, diverse groups and increased the risk of spread outside neighborhoods.

A map of accessible state-owned medical hospital centers, overlaid with protest hotspots in September – November 2020 [Created from data by ACLED.com US Crisis Monitor and NY.gov]

Essential workers in driving and delivery services roles sustain exposure risk from work that requires pickup and drop-offs of people and/or goods to a range of locations. Doug N., a Lyft driver frequently makes the common commute across the bridges between Manhattan and Brooklyn, picking up and dropping off people between these boroughs. “Sometimes Brooklyn is very busy, sometimes empty… a lot of people go downtown [Manhattan] then come back home.”

Some drivers are still cautious of putting themselves at risk. “I didn’t drive for a while, but my buddies said it was safer now, so I’m driving again,” says Ken, a Lyft driver who chose to share only his first name and who only recently reactivated his account in October. For many drivers, the risk of exposure during the course of work is a roll of the dice. Despite precautions, they can never fully know where they’ll be asked to go and who they’ll carry in their car.

NYC essential workers in emergency care services are also exposed to increased risks that are difficult to predict and control. While they may not travel between neighborhoods as part of daily work, they often need to support an ongoing stream of ill patients who do. Additionally, while medical centers typically serve their local communities and patient flux differs hospital to hospital, transfers happen in cases where the external site does not have sufficient expertise or equipment to service patient needs. This adds to the challenge of contact tracing between neighborhoods during hospitalizations and increase exposure risk for health workers.

Urgent health care providers across the board face challenges supporting diverse patient needs during the pandemic. A psychiatrist source at a large tertiary care center in Manhattan speaking without representation shares, “Before the pandemic there were a lot more in-person interpreters, now we rely on phone interpreters and this has been difficult… We’re going longer without the type of support people need, and we’re seeing worsened psychiatric needs.”

Caring for Diverse Populations and Beyond

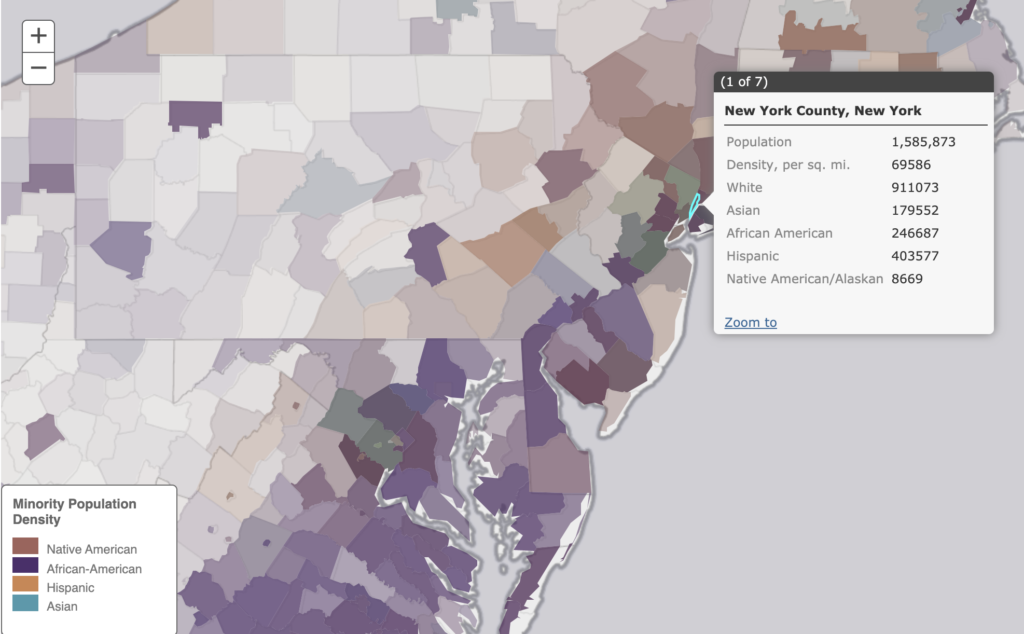

Current measurement metrics for micro-clustering restrictions in New York City boroughs are skewed towards rolling test positivity averages, which are difficult for communities with trouble accessing testing centers, while hospitalization numbers are lagging indicators that come too late to prevent spread to both the community and health workers. This challenge can be compounded in immigrant communities where access to care is limited.

The pandemic’s disproportionate toll on communities of color has been acknowledged widely in national research. The recently released AAPI One Nation 2020 Report is compiled by health policy leaders and covers the impact of COVID challenges of healthcare access, poverty, unemployment, on top of anti-Asian racism and language barriers as an obstacle to screening services. Early screening assistance would help reduce the risk of spread and avoid visits to overbooked hospitals, which limits risk to both the community and health workers.

A snapshot of NY minority populations density based off the latest US Census data.

Unfortunately, the impact of restrictions also can fall heavily on local brick and mortar businesses, key sources of income and support in some struggling communities. This can force people to take up work further away or side jobs like driving/delivery that increase their exposure risk. Escaping the cycle can be difficult for these hotspot communities, and policies should account for the need to travel and commute.

Jessica T., an EMT resident at a Manhattan hospital, remembers the difficult shifts during the pandemic months where it is common for staff to be on their feet for most of the day and work between multiple campuses. She also shares hope about the vaccine, which could help fortify essential health workers at the frontlines, though questions remain on how the vaccine should be best distributed.

“It’s a unique challenge to try to distribute the vaccine to everyone in the country and to do that in a way that’s fair [so] that the people who need it the most will receive it.”

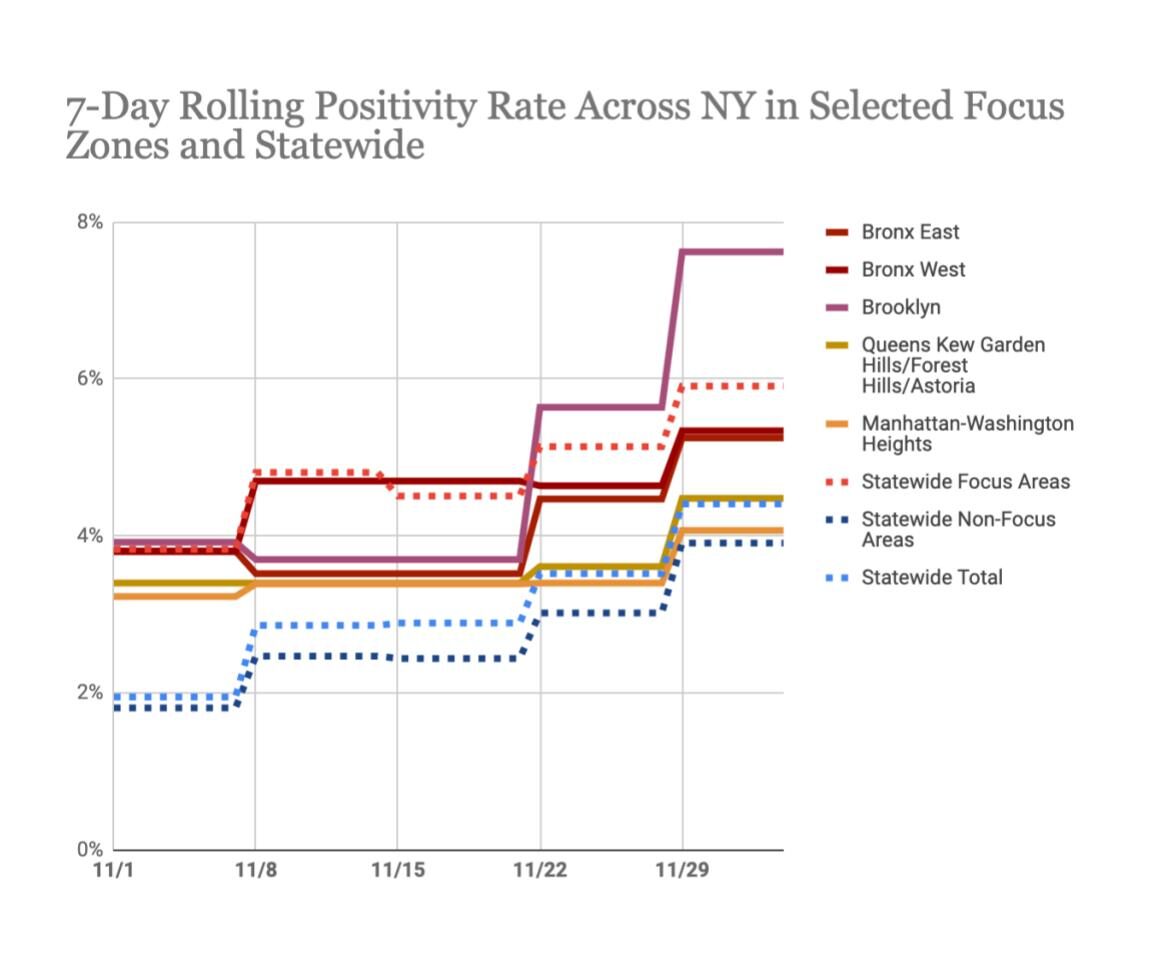

Government efforts have made progress, but as of December 3rd, the positive testing rates in Focus Zones stood at 5.91% with positivity rate outside Focus Zones at 4.49% and statewide positivity rate at 4.84%. Months after their rollout, there is little slowdown in virus growth and updates have paused on the status of designated hotspots. It seems much remains to be learned about how the virus moves through a population and where to best apply the vaccine.

Results from the first two months of Cuomo’s micro-cluster containment policy proved inconclusive. [Created from data by NY.gov]

“I hope flaws in the system were exposed by COVID will not be forgotten, we have the opportunity to use what we’ve seen for the past eight months so that we can change things for the better.”