In November 1959, a World War II veteran turned writer embarked on one of the most unusual and provocative social experiments of the 20th century.

John Howard Griffin sought to learn the truth about the Deep South’s racist culture, going undercover in a manner that, today, could be interpreted as comical or offensive. At the time, however, his investigative journalism published in the Black magazine Sepia and later a book, Black Like Me, was heralded for validating Black Southerners’ claims of harassment and injustice on many levels.

Through a series of treatments involving skin-darkening medications and ultraviolet light, Griffin changed his skin color, shaved off his straight hair, and stained patches betraying his Caucasian complexion. Then after sharing his plans with a few contacts at the Black-oriented Sepia magazine, he slipped into his new guise, infiltrating Black communities across Louisiana, Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi for a month while undercover. He quickly recognized the squalor and destitution Blacks were forced into by the white patriarchal system which had insisted to outsiders that “the Negroes” were treated fairly and compassionately.

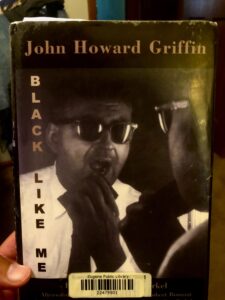

On the cover of the 2004 reprint of “Black Like Me” by Wings Press, John Howard Griffin is seen in his “Black” guise in 1959. [credit Brian Bull]

Griffin would also see the effects of disparate justice on Southern Blacks, including the infamous Mack Parker lynching case. In an era of heightened racial injustice, a Black truck driver who had previously served in the Army faced damning accusations that he had raped a pregnant white woman in Mississippi. An all-white jury indicted Parker of rape, sending the veteran to Pearl River County Jail in Poplarville. An angry organized mob dragged Parker from his cell with the help of a jail insider before severely beating and murdering him. The mob dumped his body into a river as the murder caught national attention. The FBI had even provided extensive information on the case, including confessions from some in the mob.

“The news had spread over the quarter like a wave of acid,” reflected Griffin. “Not since I was in Europe, when the Russo-German Pact of 1939 was signed, had I seen news spread such bitterness and despair.”

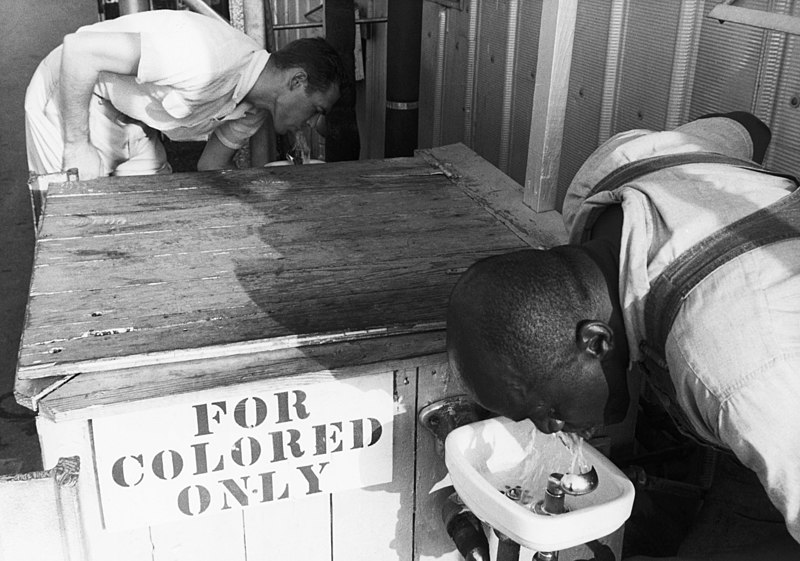

The segregated South gave Griffin unusual insights into how whites regarded Blacks. While a Black man could draw quick and brutal retribution for talking to a white woman or even looking at her — including those on movie posters — white men would often post neatly-typed notices in Black restrooms, offering money for sexual experiences with women of varying ages “from two dollars for a nineteen-year-old girl up to seven fifty for a fourteen-year-old and more for the perversion dates,” according to Griffin’s accounts. And white drivers would often pick Griffin up and cheerfully ply him with increasingly risqué questions about the sex lives of Black men, often with the notion that Black men were Herculean in libido and stature in the bedroom.

“In these matters, the Negro has seen the backside of the white man too long to be shocked,” continued Griffin in his November 16th entry while in New Orleans. “He feels an indulgent superiority whenever he sees these evidences of a white man’s frailty. This is one of the sources of his chafing at being considered inferior. He cannot understand how the white man can show the most demeaning aspects of his nature and at the same time delude himself into thinking he is inherently superior.”

Griffin also described the “hate stare” while trying to buy a bus ticket at a Mississippi Greyhound bus station. The ticket seller expressed her hostility at him with such intensity that he was taken aback. After some heated back-and-forth, she allowed Griffin to buy a ticket but flung it and the change at him and the floor. Another white traveler glared at him while waiting for the bus, prompting Griffin to write:

“You feel lost, sick at heart before such unmasked hatred … you see a kind of insanity, something so obscene the very obscenity of it (rather than its threat) terrifies you.”

The recurring abuse Griffin experienced while posing as a Black man ranged from callous indifference to systemic denial of his humanity. He saw this treatment affect Black Southerners in significant ways: from self-loathing to helping each other learn how to navigate the deeply-ingrained oppression they faced, from locals to lawmakers.

It’s important to note that Griffin dealt with fear, doubt, and isolation routinely through his experience. He didn’t put on any airs that what he was doing would necessarily fix the polarized climate of the Deep South. He also acknowledged that this was a temporary experiment, and after a month, he’d cease the medication and ultraviolet treatments, becoming his white self once more.

In mid-December of 1959, Griffin returned to his family and home in Mansfield, Texas, a life of comfort and privilege many Black Americans could only dream of. With a journal of his observations, he felt both relief and angst upon his next step.

In April 1960, the issue of Sepia detailing Griffin’s undercover activity as a white man posing as a Black man in the South hit newsstands. Griffin found himself celebrated by many prominent journalists, including Mike Wallace of CBS, New York radio newsman Ted Lewis, and Radio-Television Francaise.

While the overall response was positive, backlash erupted from bigoted whites who must’ve felt that their superior culture was infiltrated by a traitor in their midst. In downtown Mansfield, an effigy of Griffin was strung up on a traffic light on downtown Main Street: a half-black, half-white dummy with a yellow stripe painted down its back, with his name on it. Other threats against him followed, including some vowing he’d be castrated.

When Griffin’s accounts were published in 1961 as the book Black Like Me, many Black scholars and civil rights activists were quick to praise it. It sold 10 million copies and won acclaim from outlets such as Newsweek and The New York Times. It was translated into 14 languages and inspired a movie.

On the flip side, Griffin paid a price for his work. Throughout the rest of his life, he said he was reportedly shadowed by law enforcement and the Ku Klux Klan whenever he toured the Jim Crow South, and the threats never fully abated. After his appearance on TV and print journalist Paul Coates’ program in 1960, his mother took a call from another woman who said Griffin had “just thrown the door wide open for these niggers, and after we’ve all worked so hard to keep them out.” The woman then suggested some threats against Griffin should he return to his Texas community, prompting him to call for police surveillance of his home and his parents. Five months later, unable to endure the hostility and animosity of the locals, Griffin, his family, and his parents moved to Mexico to start anew.

An April 11th entry in his book, Black Like Me, shows Griffin’s tenacity in the face of blowback, particularly from Mansfield townsfolk who said they’d wanted to keep things peaceful but that he had “stirred things up.”

“This is laudable and tragic,” begins Griffin. “I too, say let us be peaceful; but the only way to do this is first to assure justice. By keeping ‘peaceful’ in this instance, we end up consenting to the destruction of all peace — for so as long as we condone injustice by a small but powerful group, we condone the destruction of all social stability, all real peace, all trust to man’s good intentions to his fellow man.” (I couldn’t help but sense an echo comparing the townspeople’s resentful lament to 2020, when white counter-protesters charged that Black Lives Matter activists were agitators and that ‘all lives matter,’ ignoring the deeper message that Blacks were being systematically oppressed by the modern American justice system.)

The most disturbing attack against Griffin was when he was driving through Mississippi in 1964. When he had car trouble, he waited by the roadside expecting help from an approaching group of white men. Instead, he was beaten with chains and left for dead.

Still, Griffin and his works endured. By the time he died in 1980, many communities had seen changes in how Blacks were treated, including those that had elected their first Black mayor or lawmaker. Schools were desegregated, and deeper introspection about America’s role in slavery and oppression of African Americans was coming out in popular media, which would include 1988’s Mississippi Burning. It’s hard to definitively measure what effect Griffin’s book had on this, but many attribute Black Like Me for illuminating how pervasive and established racism was in the South.

It’s also hard to gauge how well a stunt like this would go over today. With more people calling for greater authenticity in casting racial/ethnic movie and television roles these days and decrying Halloween costumes that let anyone portray Native Americans and Asians, it’s possible Griffin’s stunt could have been scorned by the very community he sought to support. In a commentary for The Guardian in 2011, author and journalist Safraz Manzoor speaks of the importance of Griffin’s experience but adds, “the idea of a white man darkening his skin to speak on behalf of black people might appear patronizing, offensive and even a little comical.”

One important thing that Griffin did in advance of his undercover work was coordinate with several principal staffers of the Black-founded Sepia magazine, who found the concept incredulous, potentially dangerous, yet intriguing (this included Adelle Jackson, an African-American woman who was its editorial director.) Having their consent and support gives Griffin’s efforts essential validation.

It’s possible that with today’s prevalence of smartphones, Griffin’s efforts to document racism in action would not be necessary. Social media has many examples in recent years of people committing racist acts or using slurs against Blacks and other people of color, often leading to widespread condemnation and consequences.

Then again, Griffin’s undercover work may have played a part in our society’s greater enlightenment of how racism is perpetuated in both the shadows and broad daylight, advancing the dialogue more than it would have without them. There was no doubt in Griffin’s mind that to get the raw, unfiltered view of prejudice against Black Southerners, he’d have better luck posing as the target of bigotry than a detached white observer. Given the prevalence of racism — and the fiery outcry expressed by whites after Griffin’s accounts went public — I’m strongly inclined to agree.

Black Like Me remains a pivotal work that tore the façade of Southern genteelness away, giving readers an unflinching look at how whites treated their Black neighbors then — and perhaps an understanding of how those attitudes still lurk under the surface today as we see the rise of white nationalism and hate groups grow, more than 60 years after his undercover work.