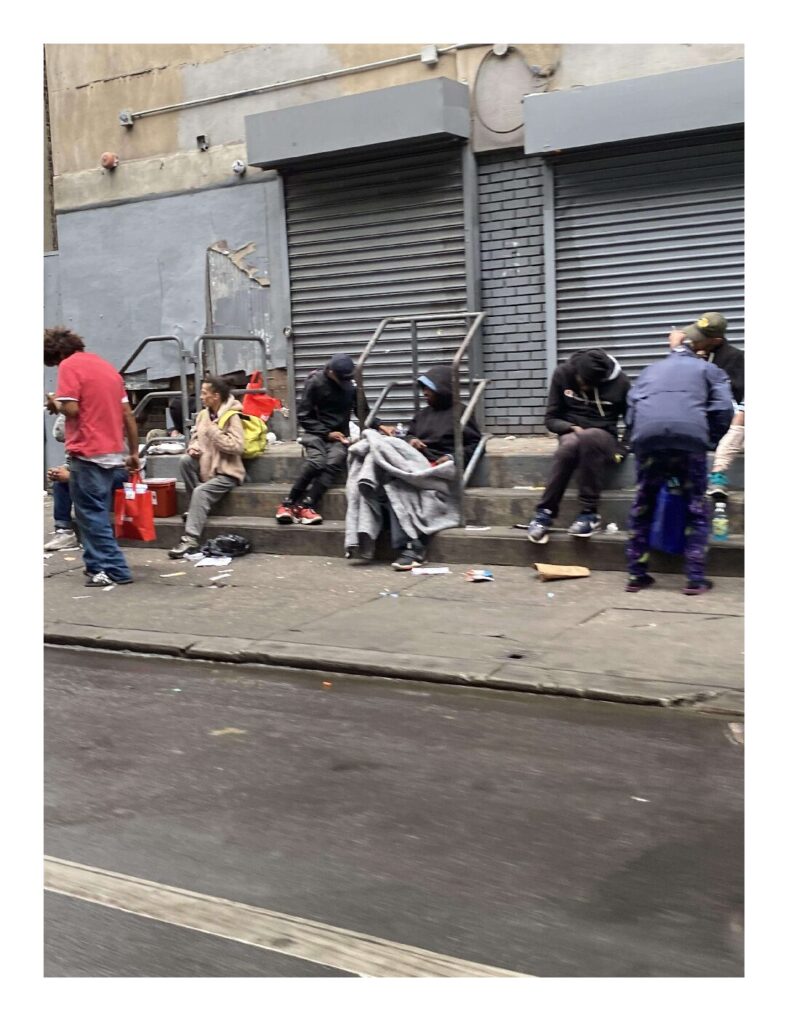

(KENSINGTON, Philadelphia) — On Kensington Avenue, a block from the Allegheny Station on the Frankfort Line, about six miles Northeast of Philadelphia, dozens of people can be seen sprawled out on both sidewalks of the avenue. Some bodies are lying flat on the cold and dirty cement. Another dozen users sit crowded on the pavement. Some, out in the open, can be seen injecting themselves in their forearms or, more frequently, one person handles the needle while the other receives the pump. This chilling scene is not an uncommon occurrence in pockets of Kensington Avenue — day and night. The drug inspiring the crowd is known as xylazine, or “tranq.”

Tranq is the street name for the substance often used in anesthesia as an animal tranquilizer. The sedative is mixed with more traditional opioids more familiar to the mainstream, such as fentanyl or benzodiazepines. It can be injected or snorted, and once taken, the drug’s effect slows a user’s heart rate, and a high lasts usually no more than 50 minutes. Xylazine is highly addictive and has a devastating impact on its users. After extended use, taking the drug causes people’s skin to rot as painful and open sores develop throughout the body.

A kilogram of xylazine can cost between $6 and $20, while the same amount for fentanyl could be purchased for $10,000 to $90,000, according to Hopkins Bloomberg Public Health. Because xylazine is so cheap, it has proliferated throughout the United States (48 out of the 50 to be exact). The cheaper prices make it easier to buy from dealers who purchase their supply from a number of possible sources — most likely from China.

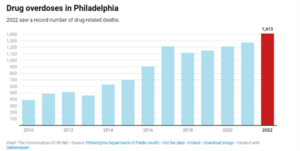

In 2021, the mayor of Philadelphia, Jim Kenney, announced an investment of $7.5 million that was being outsourced for the Kensington neighborhood alone to tackle the growing xylazine crisis that was unfolding. The area’s reputation for being an “open-market” drug hub has fed into the growing severity of tranq sales. According to a report by CBS, toxicologists in the region said 90% of Philadelphia’s dope supply has xylazine present in it. The latest report by the city illustrates an 11% spike in overdose deaths related to tranq use.

The path to curb the rapid rise in opioid deaths in Philadelphia has been expensive and tumultuous. Despite the mayor’s push for funding the opening of injection sites, which are places where drug users can inject themselves under the supervision of health care providers, the local city council rejected the opening of such physical sites, even though a couple has already opened in New York City, proving it can be done.

However, the disagreement between the mayor and city council has ignited a fierce debate between the opposing parties. The two entities’ inability to come to an agreement has put the entire plan to move forward with implementing injection sites on the back burner. During official public hearings from last September on the disagreement between the mayoral office and the city council, experts from the Philadelphia community vouched for the implementation of government-funded injection sites. It was during this time that official changes could have been made. However, the bill to approve the opening of these sites was overwhelmingly rejected in a 14-2 vote.

Starting January 2024, there will be a new mayor and supporting staff. The new mayor’s stance on this issue is more punishing of drug users and dealers and is completely anti-building out injection sites. But how any plans to curb the opioid crisis in Philadelphia will turn out is open for debate, and its success or lack thereof will not likely be known for some time.

“This is a crisis,” Jamie Gutier, a councilwoman from the 3rd District who voted to reject the opening of injection sites in Philadelphia, said during the vote hearings in September.

Quetcy Lozada, who represents the city council for the 7th district, which includes Kensington, has been a loud voice in this fight and has a plan of her own to deal with this crisis. She spearheaded the effort to stop the city from opening the safe injection sites. This February, she proposed developing a comprehensive “Marshall Plan” for Kensington.

At the core of Lozada’s “Marshall Stabilization and Recovery Plan” is the promise to bring together leaders from across the city, from public government agencies to non-profit entities to private organizations, to work together, develop solutions together, and ensure the investments are going to where funds are most needed and can be most effectively distributed within the 7th district that Kensington is part of. Lozada believes that to curb this crisis, it will require coordinating all entities’ efforts. However, the plan is notably vague, but Lozada claims otherwise.

“There was no mechanism for us to track what services people were receiving,” Lozada said when interviewed by the Click. The next step for the Marshall Plan is to assess what programs have been successful and which programs the government should continue to support. “This administration has had eight years to fix a problem they created. They chose not to,” Lozada said during the council meeting hearing on September 23.

Lozada believes Mayor Kenney’s decisions over the past eight years have made Kensington “ground zero” for narcotics use, sex work, illegal business, and dumping. “The streets where children walk to school are full of needles, drug addicts, fights, and gun crime is on the rise. They have been suffering for a long, long time,” Lozada said.

Because Philadelphia has cracked down on opioids and drugs in every part of the city except in Kensington, the message, according to Lozada and other city council members, is that this neighborhood is a ‘free for all.’

“If you do drugs in any of the other neighborhoods, you will have swift consequences, but if you do drugs in Kensington, you won’t be arrested, you won’t be stopped, and you won’t have any other issues,” said Jabari Jones, a resident of Belmont neighborhood in the Third District in her testimonial during a public council session on September 14, 2023.

Thus far, Lozada confirmed that the city council held two community public hearings—one to hear from residents about their needs and concerns and the other from the city departments about the resources allocated to curb this crisis in Kensington. As a result of these hearings, the council is expected to receive recommendations from city officials on a plan to tackle the situation. When the new mayor takes office, clarity on these plans will become public knowledge.

Meanwhile, through these public hearings, which occurred through the summer of 2023, Lozada and her team identified some initiatives classified as “low-hanging fruit.” These include a 24-hour cleaning pilot, a collaborative effort across multiple government and nonprofit agencies, including SEPTA, to keep Kensington streets and public transportation clean and accessible and ensure all agencies work in a coordinated manner rather than overstepping onto each other or duplicating efforts. The priority areas are those streets where children walk to and from school and other recreational parks. In addition, the city council installed crossing guards and speed bumps around these priority areas.

But the most striking difference is how the Philadelphia Council is shifting towards policies more in alignment with police involvement, which directly contrasts with the current Kenney administration’s focus on harm reduction.

Confidence in the Marshall Plan being effective depends on who you talk to.

“Unlike HIV, these epidemics end up in the most vulnerable populations, and the increase is in brown and black communities. Arresting more people will not work; more policy is not the answer,” said Ronda Goldfein, Board Member of Safehouse, a non-profit organization leading the opening of the supervised injection sites in Philadelphia, and also the Executive Director of AIDS Law Project of Pennsylvania.

According to Prevention Point Philadelphia (PPP), a non-profit that focuses on providing social services for communities in need, 30% of its staff pool lives at the heart of the tranq epidemic in Kensington. The non-profit believes that the most effective way to help drug addicts is to create opportunities to build trust and develop long-term relationships with persons addicted to drugs.

PPP was born in the 80s to help curb the HIV epidemic by providing clean syringes and other educational programs. In 2019, researchers from George Washington University concluded that Prevention Point averted 10,592 HIV cases from 1993 to 2002, saving $182 million in taxpayer dollars. According to their most recent report, 357 individuals were newly added to their Medication Opioid Disorder program (MOUD), up nearly 60% from 2021.

“These conversations require us to meet them where they are, and this is what Prevention Point offers,” said Hilary Disch, Prevention Point Philadelphia’s Communications Manager, when interviewed by The Click. Prevention Point Philadelphia’s goal is to take their experiences and learnings from dealing with HIV to the opioid crisis in Kensington.

But for Lozada, the short-term goal is clear and is already in the works– move the drug addicts out of the streets, clean the streets and public parks, and improve the quality of life for the families living in Kensington. She believes many of those people with an addiction in Kensington are not from the area and come here because they can buy these potent drugs cheaper and consume them openly.

“We have to make them uncomfortable; if not, they will stay,” Lozada said. The goal is to get those who are residents to the Police Assisted Diversion Program (PAD) and work with the non-residents to bring them back to their families and communities for social support. In the long run, Lozada wants a tighter connection between organizations and law enforcement to make these programs more mandated instead of being as voluntary as they are now. The timeline for when this will be implemented is, however, unclear. “We are at the early stages of this process,” Lozada said.

Currently, the PAD already works to divert people struggling with mental health issues, home insecurity, or alcohol or drug addiction to service providers that run prevention and recovery programs for the city. In 2019, PAD launched a ‘Co-Responder pilot,’ which deploys behavioral health professionals with Philadelphia police officers to facilitate health-centered interventions through targeted outreach. The Co-Responder pilot has referred over 65 people to its services and directly engaged with over 800 people in the community. Whether these statistics attest to the program’s bandwidth is not clear, and Lozada did not comment on the PAD’s success or lack thereof.

On the other hand, Safehouse’s board member Goldfein is clear about the success of the injection sites. She believes that, at the core, the issue is that the council of Philadelphia said no to an evidence-based solution and that it worked in over 100 locations across the world for over 30 years. “They ignored the experts,” she said. “Instead, they are trying things that have not worked or not worked enough.”

The question again is whether all parties can come to the table to work together. According to Goldfein, the Safehouse has attempted to contact the city council multiple times but has not received a response. According to Lozada, the mission of these harm-reduction organizations has since been diverted, and their goals have shifted. “I think currently they are more of a detriment to the community than helpful,” she said.

“We just selected a new mayor, and I think that we are in a different place today, and over the course of next year or so, we will see a difference,” Lozada said. Philadelphians hope so.