STAFFORD, VA — A year ago in Barcelona, the sky cracked open over Primavera Sound—the genre-blurring global festival Princess Superstar affectionately calls “the Coachella of Spain.” Rain fell sideways as she took the Steve Albini Stage, soaked in neon and nostalgia—like stepping into a Y2K fever dream.

She paused, blinking through the downpour—stunned by the crowd, unfazed by the storm.

“I hadn’t played in front of a crowd like that in 12 years,” she says now, leaning in over Zoom and lifting her arm to the camera. “I was terrified. But I love performing, so I gave it my all. And the crowd went bananas. It was like the universe’s light show. Oh my God—just thinking about it now, I get goosebumps.”

At 54, Princess Superstar isn’t chasing relevance—she’s watching pop culture finally sync to the tempo she set decades ago. In a moment when irony and digital maximalism dominate the charts, the contradictions that once made her an outsider now read like a blueprint. With new music, a fashion drop, and cultural momentum behind her, she’s sashaying back into the spotlight.

The Goddess Returns

Princess Superstar has always understood the power of image. From her “Bad Babysitter” thrift-store kitsch to early electroclash glam, her style has always kept pace with her sound—irreverent, ever-shifting, and gloriously hard to label.

Princess Superstar (right) at Future Music Festival in Melbourne, 2007, wearing a custom-designed outfit by Melbourne-based designer Melody Briggs. [Credit: Melody Briggs]

For her 2024 Australian tour—including a 10-costume-change spectacle at the Meredith Music Festival—she teamed up with Melbourne-based designer Melody Briggs, known for her genre-blending nostalgia and sustainable materials. Their creative shorthand, honed over years of friendship, clicked instantly.

“We’ve always worked really organically,” Briggs says. “When she told me she was coming to Australia, I showed her what I was working on and she was like, ‘This is all so on-brand.’”

Their collaboration led to a capsule collection that dropped in February 2025, just days before the release of Princess Superstar’s new single, “Goddess.” The limited-edition line—graphic tees, cheeky underwear, and retro silhouettes—channeled the same attitude as the track: sexy, surreal, and brimming with bite.

Princess Superstar wearing a tee from her “Goddess” capsule collection. [Credit: Melody Briggs]

The song, dreamed up years earlier, finally found its moment. Mastered at Abbey Road Studios, by Geoff Pesche—best known for engineering the Spice Girls’ “Wannabe”—“Goddess” lands like a self-mythologizing club banger.

“It’s not an album—it’s a mixtape,” she says of “The Serve,” due out later this year. “That means no rules. I’m not trying to chart. I just want to have fun again. It’s ‘here you go—take it or leave it.’”

The “Goddess” video channels both empowerment and discomfort. Drenched in a thick amber liquid meant to resemble honey, Princess Superstar appears luminous and alien. The secret? Soap.

“The director found this shoot of models covered in honey and wanted that look,” she said. “But we used this amber soap, easier to clean, same effect. Let me tell you—it was freezing. I was in this warehouse, miserable, but trying to be sexy.”

The layers run deep. “It might sound like a fun party song, but there are little messages in there. I like that kind of spirituality—it’s not literal or in-your-face.”

On May 12, the Goddess Remix EP dropped with five new versions, each reframing the track’s seductive bite through a different lens.

The Anti-Pop Provocateur

Born Concetta Kirschner in Spanish Harlem, to a Jewish father and Sicilian-American mother, she grew up bouncing between the extremes of New York City, rural Pennsylvania, and suburban Philadelphia. That early cultural whiplash—religious, regional, and psychological—formed the backbone of an artist who would come to thrive in contradiction: performer and provocateur, intellectual and prankster, glam and grime, often all at once.

By the time she graduated from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts in the early ’90s, acting had taken a backseat. By then, she already rebranded herself as Princess Superstar—a rapping, producing, self-mythologizing disruptor in a scene still unsure what to do with a white woman rhyming about sex, power, and identity with electroclash attitude and a wink.

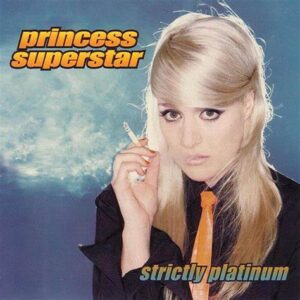

The cover of Strictly Platinum, album released 1996 [Credit: Princess Superstar]

After her all-female college band, The Gamma Rays, disbanded, she holed up in a fifth-floor East Village walk-up with a four-track cassette recorder and stitched together her first solo demo, Mitch Better Get My Bunny. This lo-fi, tongue-in-cheek manifesto introduced her as both disruptor and wildcard. She mailed it to tastemakers like the College Music Journal (CMJ) and the Beastie Boys’ now-defunct Grand Royal label. Grand Royal never responded, but she didn’t wait around.

In 1996, she released “Strictly Platinum,” a sample-heavy blend of rap, funk, and satire that didn’t fit any single lane. She called her style “flip-flop”—an intentional collision of electroclash, hip-hop, punk, and pop that baffled mainstream critics but electrified underground clubs.

Booed, But Not Broken

It was a sweltering 90-degree day in May 2002 when Princess Superstar rolled onto Central Park’s SummerStage on a plastic toy motorcycle from Toys “R” Us—one she planned to return the next morning. She was slated to open for Kelis and N.E.R.D., but Pharrell had a surprise in store: a special guest set with Busta Rhymes. The crowd wasn’t there for campy theatrics. They wanted hits.

“I think I opened with ‘Bad Babysitter,’” she recalled in a TikTok two decades later. “And the crowd was like: BOO!” She pauses, grinning at the memory. “They just wanted me off that stage. Pharrell. Busta. Anyone but me.”

Princess Superstar (L) and Pharrell Williams backstage at the 2002 SummerStage in NYC. [Credit: IMAGO]

But backstage, she got a plot twist.

“You’re dope,” Pharrell told her. “I want to work with you.”

The collab never happened, but that flash of recognition—from one of pop’s most influential tastemakers—was enough to crack the shame. That night, she swallowed the hurt with codeine and surrounded herself with friends.

“It was one of the last times I ever used drugs,” she says now. Sober for over 19 years, she sees it all differently: not a failure, but a pivot.

“Once again, I didn’t let the boos stop me,” she says. “I kept going.”

Cult Icon in the Chaos

Princess Superstar on the cover of The Village Voice, Feb. 7, 2006. [Credit: Princess Superstar]

Even when the mainstream wasn’t listening, the underground was. She became a fixture in outsider music’s most eccentric circles, teaming up with artists who prized risk over radio: Moby, Prince Paul, The Prodigy. Each collab sharpened her edges, pulling her further from pop convention—and deeper into cult icon territory. She even helped shape some of Lana Del Rey’s earliest unreleased material.

Her foray into DJ culture wasn’t a side hustle; it was an evolution. While others chased club clout, she co-founded DJs Are Not Rockstars—a name that poked fun at the trend. She hit the road in the mid-2000s, spinning alongside MSTRKRFT, Justice, Chromeo, and Peaches during the dance-punk gold rush, releasing Dance Rock Baby in 2006, a jagged, joyfully abrasive mix that bottled electroclash at its peak. “We traveled to strange places and had too much fun,” she said in her Village Voice interview, “But I always took the music seriously.”

When Camp Predicted the Future

In 2005, she released her most ambitious work: “My Machine,” a sci-fi concept album

Princess Superstar (center) with Felix da Housecat and Melody Briggs at 2007 Future music festival in Sydney. [Credit: Melody Briggs]

about a future where identity is bought and sold. Mocked at the time for its camp and weirdness, it now feels eerily prescient. Algorithms, AI clones, commodified personas—it’s all here, nearly 20 years before those anxieties hit the mainstream.

While the industry often sidelined her, queer communities and underground club scenes never forgot her. With her bratty wit, glitchy pop aesthetic, and high-camp femininity, she carved out cult status long before TikTok caught up.

That blend of irony, hyper-femininity, and chaos? It’s now embedded in the DNA of today’s pop stars.

Charli XCX’s brat-pop swagger? Slayyyter’s glam-trash meets glitchcore visuals? It’s all part of the lineage. Even Lady Gaga’s early art-school maximalism echoes Princess Superstar’s playbook.

In a world where nostalgia loops and irony sell, she’s not just being rediscovered—the culture’s catching up to where she’s been all along.

Full Circle in Venice

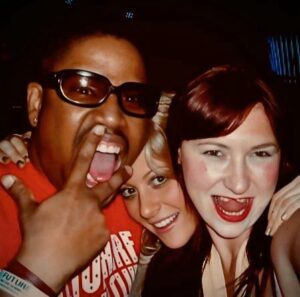

Fatlip and Princess Superstar (right) meet for the first time on Valentine’s Day 2025. [Credit: Ben Kaller]

Earlier this year, Princess Superstar reconnected with director Ben Kaller—aka Benzo—the visual mind behind her infamous “Bad Babysitter” video. They met on Valentine’s Day at a bar tucked behind a Ross Dress for Less in Venice, California, before heading across the street to see The Pharcyde at The Venice West.

Though Benzo had once directed his debut music video for Pharcyde member Fatlip with his funk rap fusion track “Worst Case Scenario,” the two artists had never met—until that night.

“I said, ‘This is my friend Concetta—she goes by Princess Superstar,’” Kaller recalled. “And Fatlip lit up: ‘You’re Princess Superstar?’ She was so flattered.”

Backstage, past collaborators converged in a rare moment of full-circle synchronicity. “She had that fearless, genre-hopping energy even back then,” Kaller said. “Her flow, her humor—it just made her unforgettable.”

Her Primavera set closed with a thunderous reboot of her 2007 hit, “Perfect (Exceeder),” reborn for a new generation. As the David Guetta remix blared and lightning cracked overhead, it didn’t feel nostalgic—it felt urgent.

“I thought my days were over,” she says. Her voice is even, but pride hums just beneath it. “But I never stopped. So when the moment came, I was already there—ready to take it.”