(SHANGHAI) — Sitting around the dining table with her husband and friends on a recent weekend afternoon, Melissa Risenhoover surveys her spacious apartment on the outskirts of Shanghai.

“We’re getting rid of everything,” she says ruefully with a gesture, “so if you want something.” Her voice trails off. Other than their two cats, two bass guitars, and a violin, everything from their past three years in China will have to fit into their luggage — or be left behind.

The impending move came as a surprise for Risenhoover and her husband, Brandon Risenhoover, who are on their second round of living the expat life. The two had sheltered childhoods growing up in “the Bible Belt” of suburban Oklahoma, but they yearned for something different. “It was never ‘I hate this place,’” she recalled. “It was, ‘I gotta see what else is out there.’”

The Risenhoovers are part of a growing community of Americans who choose to live abroad, including service members, business people, students, retirees, people holding dual nationality, and digital nomads. More than five million live outside of the U.S., with most of them in Canada, United Kingdom, and France, estimates the Association of American Residents Overseas, a non-partisan, non-profit advocating for the rights of Americans living abroad since 1973. As Americans prepare for Donald Trump’s presidency 2.0, that number may rise.

In the days and weeks since the election, news outlets have reported that online searches for how to move out of the U.S. have skyrocketed. Google searches for ‘move to Canada’ jumped more than 1000% and the Immigration New Zealand website reported a sharp uptick in new visitors.

Melissa Risenhoover and her family while traveling in China (Credit: Melissa Risenhoover)

Jess Drucker, a relocation strategist working with the LGBTQ+ community, says interest has jumped. Since the election, her Queer Expats Facebook group has grown from 700 members to nearly 4,000.

“The fish just are literally jumping into the boat,” she says.

Drucker says for her clientele, there’s anxiety over how policies may impact them. “Now people are moving out of fear. We don’t know what will happen,” she says, adding that she encourages her clients to think about moving abroad not just as an escape but also as an adventure. “It can be awesome and life-changing and fulfill you,” she tells them.

That sense of adventure was what propelled the Risenhoovers to move to Germany in 2015, as Trump campaigned for president, although they were also happy to distance themselves from American politics, they say.

“I think one of the reasons why we were so happy to leave in the first place is because we can kind of see this was happening,” Brandon Risenhoover says, referring to Trump’s rise to power. The two, who were raised in Republican families, have a more liberal outlook than their families and are registered Independents.

Their decision to move abroad was also for a better lifestyle for them and their three children. Brandon could earn more money teaching in an international private school abroad than at a public school in Oklahoma.

After a year abroad, they returned to Norman, Oklahoma to help with the family business, and quickly realized that was a mistake. “We need to show our kids more than what we’re showing them here,” Melissa told herself. In 2021, they sold everything and moved to Shanghai with their three kids in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic for a job at an international school.

They hoped to live abroad indefinitely, Melissa says, enjoying the diversity of worldviews they find among expats here, and the feeling of safety they have in Asia, which has stricter gun laws than the U.S. Brandon’s teaching salary also stretches further in China, where the cost of living is lower.

“In the U.S. we’re pinching pennies and we’re watching where every dollar goes; here, we can go get boba tea. We can go get a coffee,” Melissa says.

Clem Courtney performs stand-up comedy and storytelling in his spare time in Shanghai, China. (Credit: Alejandro Scott)

Trump’s presidential campaign also propelled Texan Tyson Peveto and his wife to move abroad seven years ago. The two started thinking about moving abroad while Trump was running for president in 2014 and a month after his election, his wife signed a contract for a job as a speech therapist at an international school in Thailand. They later moved to Germany and now live in Shanghai.

Peveto says they were deeply troubled by Americans’ reactions to Trump’s comments on immigrants and disabled people.

“I didn’t want to be around the millions of people that were okay with that,” he says. “So it was more than him, really.”

They also worried about the curtailing of reproductive rights in the United States, especially after Peveto’s wife suffered a miscarriage. Now the parents of a nine-month-old baby boy, Peveto says that before the election, his wife was leaning towards returning for just a year or two so her parents could spend more time with their grandchild.

“But then, once Trump was elected, she was like, ‘I guess we can’t do that,’” he says.

Instead, they’re committing to a life abroad, and are talking about moving to South America in the future, which would allow them to be closer to family without having to return to the U.S.

While the number of online searches related to moving abroad has risen, relocation companies are seeing a 20% downward shift worldwide in companies moving their employees abroad, says Jason Will, the China Country Manager for Asian Tiger Relocation Services. That’s for economic and geopolitical reasons, he adds.

“When they do move people around, the demographic is changed a little bit,” he adds, citing the cost to employers of schooling and housing for the decrease in large families moving abroad. “They’re more younger, they don’t accumulate a lot of furniture, so smaller shipments.”

The average cost of moving abroad can vary widely, but international schools typically do not cover the costs of large shipments, although teachers can expect visa support, a one-time moving allowance, a monthly housing allowance, and travel stipend.

Jess Drucker, the relocation strategist, says that while moving abroad can be lonely and difficult, it also offers a reprieve from the micro-stressors of daily life in America.

“There is this level of calm that exists because the worst-case scenario is often deleted — like your child will not get shot at school, you know you will not go bankrupt for health insurance reasons,” she says. “That alone is pretty big.”

Clem Courtney, a forty-something, Black gay man from Chicago, teaches English writing at a private school in Shanghai and says the election results only confirmed his attitude about why he left the U.S. twenty years ago. He says stepping away from the American brand of racism, sexism, and homophobia he experienced there has been refreshing. He’s been trying to convince his friends to leave too, “especially if they’re Black,” he says. “Every Black American should leave the states for a year. It changes your perspective. It shows you that there are other ways of living.”

What keeps him working abroad are the practical conveniences, including affordable public transportation, healthcare, and cost of goods. “My upward social mobility is better outside of the United States,” he says, in terms of his cost of living, salary, and work flexibility.

“It’s great to visit” the U.S., he says, “but I wouldn’t want to live there.”

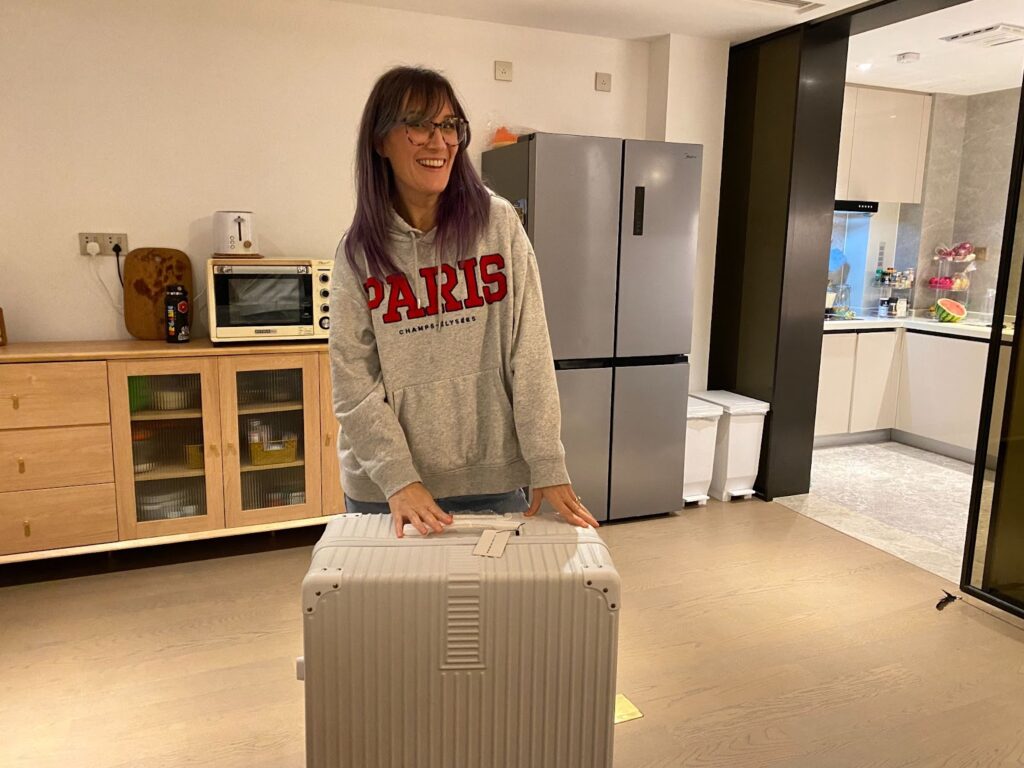

As the sunny November afternoon turns to dusk, the reality of their upcoming move finally hits home for the Risenhoovers with the delivery of a large suitcase on wheels. When Brandon was unexpectedly laid off a month ago, they were forced to rethink their plans and quickly pivoted. In two weeks, the family will fly back home to Oklahoma, to live with his in-laws, avid Trump supporters, while they settle their kids into school and look for jobs.

“Even though the U.S. is not where we want to be, we know what to expect,” Melissa says, as her 16-year-old daughter Holland sits by her side. “We know we can get through school, get them to college, and then Brandon and I will figure out what to do.”

One thing the two of them are sure of though, she says, is that their next step will likely be another stint living abroad.