(CAHOKIA, Illinois) — Arianna Norris-Landry, 60, moved to the small Illinois town of Cahokia six years ago, when her son went there to open a prepaid-wireless-phone store.

During that time, she’s seen the impact that population loss, infrastructure decay, and environmental degradation has had on the community. But these changes aren’t new: The town has been on the decline for the past 50 years, when Cahokia’s population plunged from 25,000 to 13,500 in just two generations.

“I see it in people my age and older — they were young in the 1980s when it was starting to fall apart,” Norris-Landry, who runs an after-school science club for kids, told the Click. “When you take people and grind them down for years, they are too tired to fix things. It’s really hard to watch.”

Norris-Landry is also an administrator on the Cahokia Cares Facebook page, meaning she’s had time to think about how the changing times have affected both the community and herself. “Now I’m stuck. I can’t afford to leave,” she said. “Most who could leave, have. You have a town of people of color, old, poor, disabled, a lot of people struggle every day to get by and the schools are a mess. It feels like nobody cares.”

However, Cahokia isn’t alone in its plight. Two nearby small towns have had similar struggles. USA Today named Centreville the “Poorest town in America” in 2019. Tiny Alorton also suffers from blighted properties and a declining population.

But now, a big plan has finally been put in place to fix the three towns’ woes. This spring, they will disband and form the brand-new city of Cahokia Heights. The towns’ leaders hope the merger will be enough to save them. And if the gamble pays off, it may serve as a blueprint for other American towns struggling with population loss.

A FATHER, A SON, AND A PLAN FOR THE FUTURE

Curtis McCall Jr. is the 39-year-old mayor of Cahokia, and he’s still fighting for his community’s survival. That’s why he supported the merger plan, even though he knew it would put him out of a job. “It was a difficult decision but in my heart, necessary. I was the first Black mayor, I worked hard to get here. But my wife and son are a part of this community. And I had to think of the people who elected me,” McCall Jr. told The Click.

His father, Curtis McCall Sr., is the Centreville Township supervisor. He was also a proponent of the merger campaign, which passed with 61% voter approval in the November 2020 elections.

Around three years ago, McCall Sr. reached out to the mayors of the three towns. “[He] asked us to look at how our communities were dying year by year, falling apart,” McCall Jr. said. “He challenged us. At this meeting we thought he was talking crazy. But once we looked at the numbers, they were staggering. We knew we had to do something or these cities would not survive.”

Mayors McCall Jr. of Cahokia, Marius Jackson of Centreville, and JoAnn Reed of Alorton ended up supporting the campaign to merge their towns. The Click reached out to mayors Jackson and Reed. Jackson did not respond; Reed was willing to comment but could not be reached for an interview.

McCall Sr., who also did not respond for comment, was elected mayor of the new town on April 6, 2021. He ran unopposed. He will replace his son and the other two town leaders on May 6, 2021.

UP THE HILL OR BELOW THE HILL

The towns can be found in the American Bottoms region (also sometimes called “The American Bottom”), so called because it’s the topographically “bottommost” part of the Mississippi River floodplain in southern Illinois. The area is just across the river and minutes away from the metropolitan area of St. Louis.

The proximity to the river, fertile land, and the promise of work offered by the mineral richness of the riverbed may have originally attracted people to the area. (And not for the first time — Cahokia shares a name with a nearby ancient “lost” settlement that also faced population growth, then rapid decline.)

McCall Jr. said that the population of his city boomed in the post-World War II era and peaked in the 1970s. He said that toward the end of that decade, much of the white population began to migrate. This left the town with a dwindling headcount.

McCall Jr. said that the same is true for the nearby towns of Alorton and Centreville, which lost 47% and 57% of their populations respectively in the last 50 years. “Older people died and the children moved to more affluent areas where there are more homes, schools, and growing businesses,” he said.

A closed playground in Alorton, Illinois [Photo credit: Jenny Bird]

Below the hill, the shrinking tax base hurt just when the aging infrastructure needed repairs. McCall Jr. explained that when the Mississippi River waters flood, it shifts the ground and displaces pipes. This impacts both the water system and the roads, causing broken pipes and sinkholes.

Debbie Duncan, the assistant village clerk who has lived in Cahokia all of her 62 years, said that the main problem in town is the sewer system. “The sewers have been an issue since I was a child,” she told The Click.

Many of the infrastructure problems lie underground and are not immediately obvious to the naked eye. Driving through Alorton, Cahokia, and Centreville, they appear nondescript. Like other typical small Midwestern towns, there are few sidewalks, more stop signs than stop lights, and many churches. The humidity of the river climate encourages abundant plant growth; abandoned buildings are quickly swallowed up by greenery.

Despite the towns’ unremarkable appearance, the infrastructure and environmental problems here have become infamous.

Entering the area from the west you pass through Sauget, Illinois, a former Monsanto company town created expressly as a dumping ground for large corporations.

Plant in Sauget, Illinois, with the St. Louis arch in the background [Photo credit: Jenny Bird]

Closer to home, Norris-Landry’s science club gives children kits to test the level of pollution of the water in their yards, an educational activity to teach them about the ecological degradation of their surroundings. “Copper in the water appears to go up after a rain, which becomes a flooding event around here. And the pH is extremely acidic,” she said.

McCall Jr. said that despite the many difficulties, the community is more than it may appear to be from the outside.

“We have good people here. The media like to put a stigma on Black communities but never get to know the people, the Miss Williams, the Mr. Jones. We are a classic Mayberry type of town, good blue-collar working-class people. It’s a good community. But all that is covered is the negative,” he told The Click.

BENEFITS OF THE MERGER

Antonio Baxton, a former employee of the Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity and a consultant who was part of the merger planning, told The Click that the merger will be fiscally beneficial. “It will lead to more federal support: instead of three smaller communities, they can apply as one larger bloc.”

Baxton said that he played a part in submitting a $22 million grant proposal to FEMA in January with hopes of relief for the communities’ sewage issues.

“When grant makers, not just federal and state but philanthropic, consider it, they may see more bang for the buck: A larger community with a single site for managing the money of the grant,” St. Louis University Urban Planning Professor Bob Lewis said of the plans to merge.

Lewis also pointed out that the towns could gain political clout by joining forces. Cahokia would move from being Illinois’ 170th largest town, Centreville from 340th, and Alorton from 499th. By joining, they move up the list to 124th, surpassing neighboring communities.

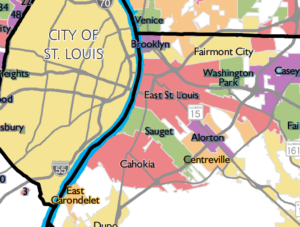

A map of the towns that will soon become Cahokia Heights, Illinois [Image credit: East-West Gateway]

The merger will also end a duplication of services. Now there are three city halls, plus separate police and parks departments. Baxton and Lewis agreed that ending duplication will save much needed money.

But Lewis offered an alternative, one that belies the merger planning. He said that river towns are a relic of another era.

“They aren’t relevant in the same way they used to be,” Lewis told The Click. “Some would say the flooding issues are that bad that we should just shut them down and locate the people to higher ground.” He cited examples of two other Illinois river communities, Grafton and Valmeyer, where the towns organized to move to higher ground after suffering devastating floods in 1993. Valmeyer in particular had success moving en masse up a bluff behind the town, using federal funds from FEMA to create new infrastructure and housing, albeit on a much smaller scale than the communities of Cahokia Heights.

Duncan, who has lived her whole life in Cahokia, rejects this idea. “I will never move. I told my kids that. They are grown, they both live in Cahokia, my daughter with me and my son two doors down. They love this town too,” she said.

When asked about moving the entire community to higher land, Baxton told The Click he could not imagine it. “This is valuable real estate across from St. Louis, 10 minutes away. The last decade there’s been a plan and tax to fix the levee so that it is at a 500-year flood level. There’s been investment,” he said.

AN AMERICAN PROBLEM

Lewis sees population loss as a problem for more than just the American Bottoms. He says he believes that many communities in the US will be grappling with population loss in the years ahead.

With the past decade featuring the slowest rate of population growth since the Revolutionary War, alongside slowing immigration rates, national population projections are not promising, he said.

“The question is where do we find more people to populate a lot of these places? And if there are in fact fewer people to distribute to these places, where are they going to choose to go?” Lewis said. “Older urban centers all over will deal with this. People will go to Miami, Chicago, or Boston if they can afford to, not Cleveland, St. Louis, or Kansas City. And where does that leave places like Cahokia Heights? It’s a big challenge for America for the next 40 to 50 years.”

However, that prediction doesn’t impact the significance of this moment for the new citizens of Cahokia Heights.

“We are doing something on an enormous scale,” McCall Jr. said. “There’s a lot of uncertainty at this time; many don’t know what to expect after consolidation.”

And while the soon-to-be former mayor stands by the plan, he knows it’s likely that the gains may take a while.

“Me and my dad may be dead and gone when future generations will reap the benefit of this,” he said.