(NEW YORK) — There’s little comic about Joe Sacco’s “Palestine.”

The series of graphic stories, published between 1993 and the early 2000s, combines the art of cartooning with narrative journalism to create a compelling portrait of Israeli-occupied territories, evoking visceral humanity in a way that written work so often fails to do.

Sacco’s “Palestine” remains as relevant as ever. Palestinian American literary scholar Edward Said called it, “A political and aesthetic work of extraordinary originality,” in his foreword of the complete volume, with credit to Sacco’s accessible approach to complex geopolitics. The basis of the book is intimate interviews with over 100 Palestinians and Jews between the West Bank and Gaza during a 1991-92 trip to the region.

What Sacco’s “Palestine” serves to the big tent of American journalism is a valuable marrying of advocacy journalism and the graphic novel format, which offers an “antidote” to the egregiously sanitized packaging of stories for broadcast news, and to the Israeli influence that saturates American media. That there are inculpable Israelis being disenfranchised by ongoing attacks between the nations is not up for debate in this story, because that’s not what the reporter came to discover at the time he sought it out.

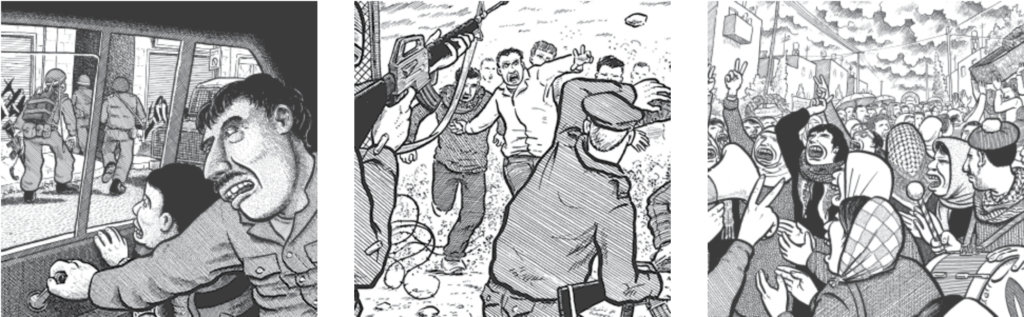

Despite its release more than 20 years ago, Sacco’s work of illustrated reporting remains singular in both genres it occupies – at once a comic book and piece of investigative journalism – and a particularly potent form of either. The artist’s compassionate attention to the subject is nowhere more apparent than in his ability to depict a gamut of emotion with a black & white line drawing – from the hash marking of shadows in faces hung low in subtle anguish, to the gently lifted, twinkling eyes of those with a spark of hope amid repeated trauma.

Furthermore, the choice to draw the scene as the author interprets it, as opposed to photographing real life, helps the characters in “Palestine” speak for themselves. Where shocking images of devastation and destruction in the sensationalized news cycle distract from the individuals within the frame, often prompting us to avert our eyes, the simplified artistic rendering draws us in just enough to force us to read and to study their face, posture, and gestures. Where words can be misinterpreted, the physicality of emotion is universal.

The care in his approach as an investigative journalist can be seen in the episode titled “Remind Me,” asking, rhetorically, “Do we need to talk about 1948?” Occurring early in the series, this section chronicles his first days in the Palestinian refugee camp Balata but also serves as a sort-of dossier of the global players – former Prime Ministers, Egyptian singer Oum Koulsoumm and American actor Chuck Norris – whose influence on culture serves as a common cultural through-line in those Sacco meets.

He also shows disarming transparency in his personal perspective, unafraid to admit his naivety to warfare – and faith. During one scene a “freaked” Sacco blabs about bombs he heard in Ramallah. In another example, he talks to professional women at an office in Gaza about the nuances of wearing a hijab – a symbol of friction between the Islamic extremist group Hamas, now the de facto governing authority of the Gaza Strip, and the secular resistance, the Palestine Liberation Organization.

“Palestine,” by Joe Sacco via Fantagraphics

“We wear it outside,” a young woman inside an office building told Sacco. Asked whether she felt obliged to wear a hijab due to Hamas, she said he’d “got it all wrong.”

“On the contrary, I want to believe strongly enough [to wear it],” she responded.

Sacco acknowledges what he does not understand, writing in an aside to the reader, “I see the gulf between us. I realize then I’ve forgotten what it’s like to have faith. I mean, I’ve forgotten what it’s like to want to have faith.”

Maltese American Sacco approached “Palestine” with an outsider’s perspective – inherently biased by American media – yet saliently condemned Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territories in his epilogue. As he wrote in his 2001 author’s note, “illegal Jewish settlements” which exist in still-growing numbers today, necessarily come with “all the consequences of occupation.”

The picture of Palestine through Sacco’s eyes is “remarkably even-handed” and “humanist in tone,” as one 2003 review of the book in The Guardian put it. His was a relatively novel take at the time when the collective of Western media had turned a blind eye to Palestine for fear of giving credence to an extremist government in Gaza. And, if we can believe his claim that he came to the project “from the standpoint of ‘Palestinian equals terrorist’,” then we can just as well believe he came to give opposing Israelis a fair shake.

What makes Sacco’s style of advocacy journalism so compelling is their power to emphasize feeling without words, telling stories in a way that cut to a person’s emotions and psychological state.

Columbia University professor Said wrote in his foreword, “There’s no obvious spin, no easily discernible line of doctrine in Joe Sacco’s often ironic encounters … [Few have] ever rendered this terrible state of affairs better.”