March 13 marked the third Sunday of Russia’s invasion of the sovereign nation of Ukraine. That day, New Yorkers flocked to the East Village to express solidarity with a nation under attack. Despite the cold weather — it was just bearble enough to be outside — women filed in and out of churches with yellow-and-blue interlocking ribbons pinned to their lapels, while groups of young Ukrainian-American men stocked up on poster boards, snacks and Gatorade at the Astor Place CVS Pharmacy in preparation for a nearby protest later that afternoon.

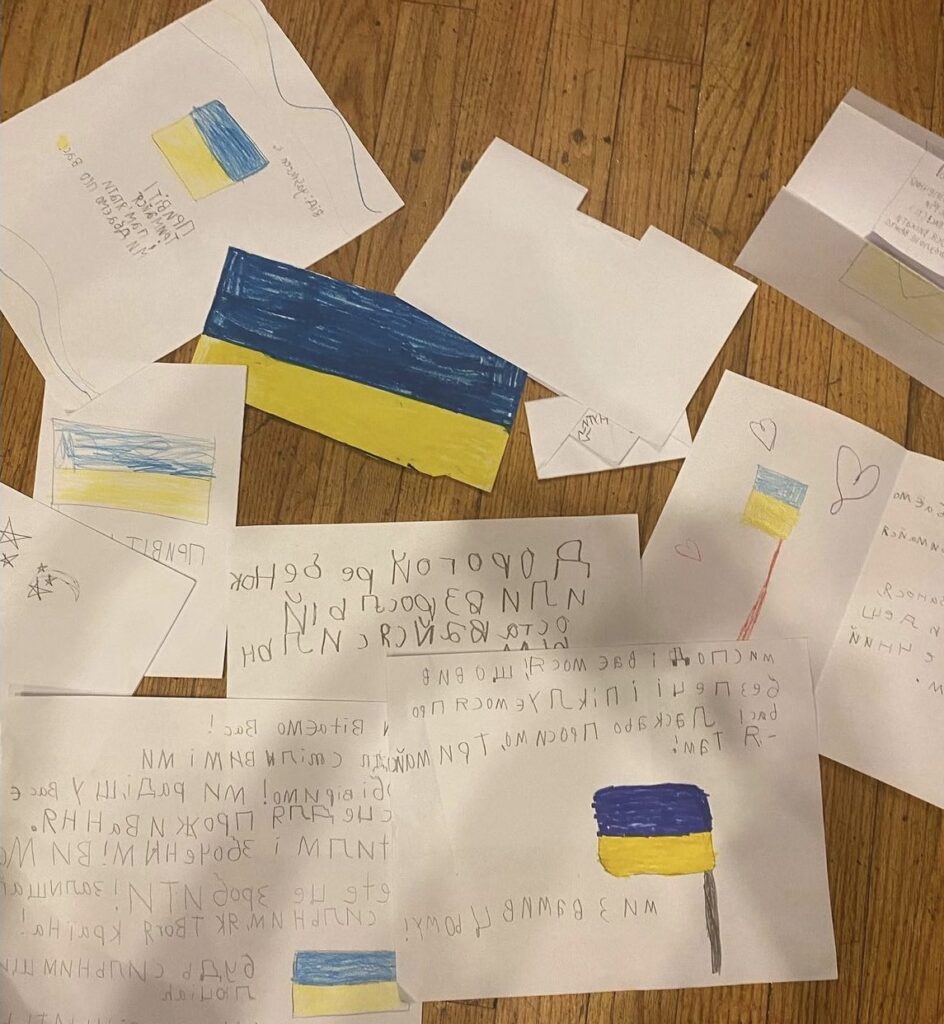

At the same CVS, I filled a red basket with supplies: bandages, burn pads, gauze, Neosporin and hydrogen peroxide. I was checking off items on a list of requests that had come from the front lines of the conflict. This Sunday was the second humanitarian aid drive organized by Svitlana Mykulynska, a 27-year-old Ukrainian-American woman, who would be sending the goods overseas later that week. Ever since the war broke out in February, she has been grappling with being so far from her home country while her family members are enlisted in the Ukrainian Territorial Guard, fighting to defend Kyiv, the country’s capital.

Mykulynska, her parents and sister had been planning to fly to Kyiv in May for a cousin’s wedding. Instead, her cousin got married on the first day of war, and the very next day signed up to protect the city from Russian forces. Her father, who was trained in long-range artillery under the USSR, flew to Ukraine on Feb. 26 to support efforts on the ground– a decision made after he regretted not supporting Ukraine on the ground during Russia’s 2014 attacks.

Back in New York City, 4,000 miles away from the fighting, Mykulynska finds herself on a different front line of the war. It’s a metaphorical battlefield of Ukrainians who are deeply mentally entrenched in the conflict, and searching for ways to protect their homeland and cultural identity without being physically there.

“In a way, it feels like it would be almost easier to be in Ukraine,” Mykulynska said while describing the emotions she and many in her inner circle are going through. “We all have a bit of survivor’s guilt being over here.”

She refers to this feeling of guilt as a driving force in making her own impact on what’s happening abroad. The Ukrainian Creative Collection, a social media page she made to share events and efforts to support those facing a direct impact on the ground, has been a way for her to connect with the local Ukrainian community in New York and add tangible actions to the war efforts in cities like Kyiv.

At a Greenwich Village coffee shop on a Sunday afternoon, Mykulynska describes the overbearing weight she feels from the conflict and her limited ability to help. She’s feeling similarly to how I felt when dropping off a shelf’s-worth of supplies at the drive, quickly realizing it was not even a fraction of what was needed to support the approximately 126,000 Ukrainian troops, additional members of the Territorial Guard and the thousands of civilians stuck in the crosshairs of conflict. Efforts on the metaphorical front lines of New York can never measure up to the sacrifices made in the war-torn Ukrainian cities, she said.

“They’re dealing with unbearable bombings and tragedies everyday,” Mykulynska said. “Past the dismantling of the Soviet Union, Russia remained an ever-present threat, but it was never up close. An attack like this was unimaginable.”

Unlike her family members witnessing the destruction firsthand, Mykulynska’s last memories area permanent vision of the country’s beauty. Growing up, she spent summers in Kyiv, immersing herself in the city’s history through personalized tours and cultural facts shared by her aunt, a children’s book author living in the city.

During the often impossibly hot days, Mykulynska and her cousins would find shade under the chestnut trees lining Sofiyivska Square, located in the city’s center. But on days when pleasant weather offered a break from the heat, they would promenade through the city, stopping for a treat at a favorite chocolate shop filled with Ukrainian sweets, while admiring the city’s ornate architecture. Churches topped with shimmering gold domes always captivated her. “There are so many churches in Kyiv, it is super spectacular,” she said.

Fond memories of a peaceful home country are also the motivating force behind Dana Kurylk’s efforts in New York. Born in Chernivtsi, Ukraine, 26-year-old Kurylk moved to the States in 2000 after her mother won a green card in a lottery.

“I feel like my mom is one of the luckiest people in the world,” Kurylk said, describing the chance awarded to her and the family. “She just has all these opportunities land into her lap all the time; or at least that’s what my dad says.”

After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, though Ukraine found sovereignty as a nation, the country faced uphill economic challenges only exaggerated under the close eye of its neighbor, Russia. At the time, the United State’s green card program was offering potential citizenship to those liberated from ex-Soviet Union territories.

Much like Mykulynska’s upbringing in the states, Kurlyk’s Ukrainian ties were a prominent part of her New York childhood.

“It was definitely a full-time presence that came in different waves and different ways,” Kurlyk said.

Her parents, never wanting her to forget where they came from, spent the early years ingraining in her lessons of their heritage and culture. She then went on to attend kindergarten at East Village Ukrainian private school, Saint George, which has an affiliation with the Catholic church. The following year was spent living with her grandparents in Ukraine to attend first grade and immerse herself in the language and identity of her homeland.

For Kurlyk’s approach, supporting the front lines is focused on education. She has found that, for many, this moment has been an opportunity to learn about Ukraine and its identity.

“The war has unleashed a Pandora’s box of people learning about our history for the first time,” she said. “Even in the scope of the enemy, though the two adversaries speak the same language, they are not brothers. It’s very much a conflict based on the colony and the empire itself.”

The same sentiment is shared by Anne Lounsbery, the Department Chair of NYU’s Russian and Slavic Studies Program, who said: “Russia, as Rusia, has always been more of an Empire than a nation, meaning the connection was by land rather than nationality and culture.”

Since the dismantling of the Soviet Union, ex-Soviet territories that shared commonalities with Russia created an appearance of ties to the larger power, rather than creating recognition of each having their own unique identities, with their own nuances. Ukraine, in particular, as a bilingual country speaking both Ukrainian and Russian, was often thought of as an extension of larger Russia. “It has always been a flash point,” Lounsbery said. “To Putin and many Russians it is viewed as the cradle of Slavic culture, and a continuation of Russian ideals.”

Kurlyk has found power in changing this narrative with the help of her community. “I feel like a steward of my culture, it is a special thing to be able to share it with others,” she said. Her immersion into Ukrainian history growing up created a foundation to help in this moment.

“It’s odd”, she said. “For a while before the war broke out, I felt like it was something I needed distance from. It could feel a bit suffocating in a way. I felt like I couldn’t just spend all my time with Ukrainians. It was a bit limiting.”

But when the first bomb dropped along the country’s eastern border, her thought process immediately shifted, thinking instead, “I need to be with my community.”

Kurlyk refers to her “core friends” as the ones made during her youth attending kindergarten, Ukrainian summer camps and Sunday school through the Ukrainian American Youth Organization she endearingly refers to as “Uki” school. This is where Kurlyk and Mykulynska became friends.

Coincidentally both of their parents knew each other from living in the same town of Chernivtsi Ukraine, only to have their daughters become friends years later, with bonds made over Ukraine.

Their friendship represents just one small example of the close relationships within the larger Ukrainian-New York community. The East Village, in particular, has been established as a hub for Ukrainianism. On the same block as Veselka, a New York restaurant serving traditional Ukrainian cuisine, Mykulynska established a drop-off location for her humanitarian aid drive. While Kurlyk reminisces on fond memories of performing traditional Ukrainian dance during the annual Saint George Ukrainian Festival parading down that same street. She is a member of the Syzokryli dance company, another example of her close connection to her culture.

Both women have found a responsibility in sharing their knowledge with the larger community. For those not on the ground, this is a war of information.

“I remember reading this article of how Ukraine is getting itself together and organizing war efforts within itself as a country, and I feel that goes for every Ukrainian in every diaspora of the world,” Kurlyk said. “In the context of this war, Ukrainians have found a way to be on the front lines of the information war, on the organizational, humanitarian aid aspect.”

As both women work towards making an impact on metaphorical front lines, they face a heavy emotional and mental toll, along with the question: How much information is too much?

Survivor’s guilt is a double-edge sword: just as it can be used as a motivator, the young Ukrainian women in New York City also find it easy to punish themselves with what they call “doom scrolls,”which means taking in large amounts of social media to relate to the pain their relatives and what fellow Urkainians face every day in their home country.

“It feels like I was living a double life,” Kurlyk explains, finding it difficult to engage and be present in social activities while knowing the tragedies occurring across the world. She has instead shifted her mentality to lean into “the love,” as she puts it. Through the pain there is a deep admiration and caring radiating from her community and people around the world. This energy fuels her.

In recent weeks, Mykulynska has taken a step back from her efforts to prioritize her mental health, because it can quickly all become too much.

“It’s really important to have a balance,” Mykulynska said. “You have to be strong in order to help people. You need energy to keep the momentum going. Sometimes you need to take a step back to continue being engaged.”

While there is no knowing when the war will resolve, both women understand that it is efforts like theirs that help further their progress. It feels as though the courage is innately in them.

“Ukraine’s history is of immigration and running from conflict, our roots have been set up everywhere,” Kurlyk said. There is power in numbers. “ We will not be not be stomped upon.”