(EL PASO, Texas) – “Going through the Darién jungle was one of the hardest parts. I remember friends telling me, only take the things that are necessary, like food. The mud was so thick that it would stick to all of my belongings,” recalls Milagros, a Peruvian immigrant who arrived in El Paso and asked to be identified only by her first name.

The Darién Gap is located between Panama and Colombia. It’s just one the many treacherous stretches immigrants must cross as they journey to the United States. It’s a roadless crossing that consists of more than 60 miles of dense rainforest, steep mountains and vast swamps, as described by the Council on Foreign Relations.

“We traveled in Dec. 2023, which is the rainy season. I saw a woman from our group walk against the river current instead of dealing with the terrain under her feet, until she was swept away,” says Milagros, who traveled almost 5,000 miles from Peru with two of her children ages 6 and 2 in search of a better life.

Milagros applied for asylum before entering the U.S. by using the CBP One App. On March 14, she reported to the Nogales Port of Entry for the appointment she made online. She and her family were processed at one of many U.S. Border Patrol facilities. An asylee who passes an interview will be referred to a judge for a full hearing on the claim, according to the Department of Homeland Security.

Asylum is defined as a form of protection available to people who: Meet the definition of refugee, are already in the United States, and are seeking admission at a port of entry. After processing, she now has a date scheduled before a judge on her asylum claim. She traveled to Texas and landed in El Paso in the month of March after running out of money.

What now, that she’s claimed asylum?

A week later, she arrived at Sacred Heart Church and is staying with her children at their emergency shelter, one of 50 or more people who eagerly await their final destination.

Sacred Heart

Sacred Heart shelter was established in 2022 when the church began helping hundreds of migrants who were released by U.S. Border Patrol into the streets of Segundo Barrio (Second Ward) neighborhood. Helping newcomers from Latin America is deeply rooted in the church’s history. Founded by Jesuits in 1893, the church has long served its Mexican immigrant community, according to the church’s website. Now, a little more than a century later it continues its mission to assist immigrants in need.

Sacred Heart Church began taking in a surge of migrants at the end of 2022. [Credit: Jennifer Mendoza}

Milagros shares her goals with The Click for the future: a house, a career, a good education for the kids, and a better future. It’s a list that many Americans can relate to.

“I also just want to start working. Once things get settled, I’d like to either get into education or cosmetology…I’ve always been interested in getting done up.”

It’s lunchtime; people inside the shelter begin to form a line by the makeshift buffet table. Families collect their food and sit at white, round tables standing in what used to be a gym. Conversation and laughter fill the air, along with the ruckus of children running freely. It’s a sense of normalcy most have seen in months.

“We had to climb an enormous mountain. The more time you spend in the jungle the more difficult the journey becomes,” Milagros says. “We saw a man who had died on the mountain. We saw so many dead in the jungle. The smell was awful. I shielded my daughter as I held her in the kangaroo wrap. My son was lifted up from the ground by an Ecuadorian family so he wouldn’t see.”

“We saw so many people dead as we passed the Darién Gap,” agrees Antonio, a Venezuelan immigrant who declined to give his last name. “We come here and we’re still being treated like we don’t matter.”

Sacred Heart residents begin their day bright and early. [Credit: Jennifer Mendoza]

A Life in Limbo

But, right now, the temporary residents live a life in limbo, after running out of money, they rely on local shelters to stay fed and clothed. Antonio and his group of friends stand across the street to be readmitted to the shelter but he has his disagreements with the way they’re being treated. “They tell us we have to leave and we can’t go back till hours later…Some of us aren’t used to this weather.” The days in El Paso are slowly warming up again but it’s April, the winds at times go up to 50 miles per hour and the dust makes it that much more unbearable.

Life at the shelter is fairly routine, it consists of waking up atop a camping mat everyday next to strangers. Breakfast is served at 8 a.m. Afterwards, residents try to find work to make their way to their next stop. Some immigrants are able to do so by filing a right-to-work permit or working jobs while being paid “under the table.”

“We’re in the process of getting our work permit from the court. Here, we work with our Mexican counterparts but they’re getting paid more than we do,” Antonio said. “They get paid $150 and we get paid $60. It’s exploitation.”

Getting a job permit isn’t an easy feat. For asylum seekers to work in the U.S., their asylum application must be pending and they can file a “Form I-765” which would authorize the asylee to work in the country. They can submit the application 150 days after filing their asylum application.

For many, the Segundo Barrio neighborhood, where the Sacred Heart Church shelter is located, is the first glimpse of American life. It still holds much of its turn-of-the-century charm with traits of the present. Murals depicting migrants or indigenous cultural roots are visible all around.

Michael DeBruhl, a retired border patrol agent turned shelter director, says he and his staff try to help as many people as they can.

“I’ve been staying at this shelter for two months,” a Colombian man waiting outside Sacred Heart tells The Click. “I left Colombia because of the war that has consumed my country…I have an appointment in New York in front of a judge soon.”

A man from Colombia awaits for the shelter to reopen its doors. [Credit: Jennifer Mendoza]

Milagros lowers her gray sweatshirt to breastfeed her daughter when her son comes by with a quarter of a quesadilla in hand showing his obvious dislike. Milagros tells him to try and eat something, a familiar battle for any parent.

Milagros’ and Antonio’s arrival along with many others comes at a time when immigration is a hot topic for U.S. politicians and citizens. In February, U.S. senators worked on a bipartisan bill to overhaul the asylum system at the border. The bill failed to gain support continuing the bitter battle over how to manage the influx of migrants at the border.

When asked about the controversy, Milagros says, “There are good people and bad people that exist. Of course, those who are criminals should be deported but I think people should understand that all of us fleeing are doing so out of necessity.”

The Dangers of Mexico

Even though Milagros and Antonio endured treacherous jungle terrain in Colombia and Panama, they say getting through Mexico was one of the hardest parts of the journey. ”I would run out of money or we would be taken advantage of in Mexico not only by the criminals but by local law enforcement,” says Milagros. “Families who would have their children kidnapped would have to pay a ransom for their safe return.”

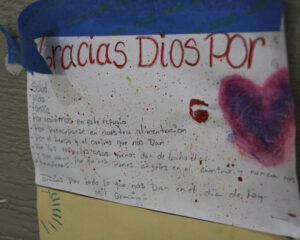

A prayer, thanking God for all that’s been given. [Credit: Jennifer Mendoza]

“Plata ó plomo,” says Antonio which translates to “money or lead.” Antonio recounts his journey through the drug-ridden cartel and corrupt country. “It’s crazy,” he said.

Despite the hardships many have faced to get to the U.S. smiles are not uncommon. Milagros dreams of raising her family with a home of their own. “I want my kids to have the best education and future…My son tells me when he sees me cry, “God is big.”

Looking at each other with tired smiles, Milagros and her daughter start to draw in a coloring book.

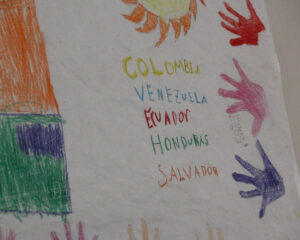

Artwork created by migrant children and where they are from. [Credit: Jennifer Mendoza]