(GAINESVILLE, Fla.) — Kayaking down the Santa Fe River reveals deep brown, organic-rich water and hints of red with each paddle stroke. A swift left into Gilchrist Blue Springs State Park and everything brightens. Beneath the crystal clear spring lies a rich underwater landscape, a sea of greens and yellows, briefly interrupted as turtles swim lazily by.

The serenity the springs offer, however, is surprisingly deceptive. Beneath the surface, the springs face a myriad of threats, including agricultural runoff, water flow, and climate change.

Florida is home to over 1,000 springs, the largest concentration of freshwater springs in the world, with the majority located in the northern and central parts of the state. They are essential habitat for plants and animals and also offer critical signs to the health of the Floridan aquifer, which is the source of 90% of the state’s drinking water. A 2015 report by the United States Geological Survey showed 15,319 million gallons of water are withdrawn each day, 62% of those were from the Floridan aquifer, for the primary purpose of utilities and agriculture.

These threats have altered the spring’s appearance over time and have been hard for those who care for them. Especially to retired Florida State Park Ranger Steven Earl, who developed a profound bond with them during his 30 years as a park ranger and a father raising children at the doorstep of Ichetucknee Springs State Park.

“When I first laid eyes on the spring and saw that crystal-clear, turquoise blue color, and all of the vitality coming out of the earth and all the plant life and wildlife that was thriving within that, I was just blown away. I was just like, ‘Oh, my God. I’ve found the center of the universe. This is home,’” he said.

Earl is a watercolor artist who draws inspiration from the springs and spends much of his time deeply intertwined with the natural environment. “The Ichetucknee became my muse. And I just spent every possible free hour I had there exploring,” he said. The springs have a deep personal meaning for him. “I consider them sacred,” he added.

Printmaker Leslie Peebles also feels a profound connection with the springs. She hopes that her art, which is heavily inspired by the Florida landscape, is an eye-opening experience for people to truly see how “astonishing” the springs are. She recalls the moment she first saw them and how profound that was for her.

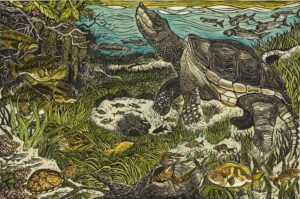

‘Blue Hole Buddies’ by Leslie Peebles, who finds inspiration in Florida’s natural springs (linocut block print and watercolor)[Credit: Leslie Peebles]

‘Loving the springs to death’

Experts like Dr. Matthew Cohen, professor of forest water resources and hydrology at the University of Florida, have spent decades studying the springs and the threats they face.

“It’s just clear to me that we love these systems a lot, but we don’t really know how to be gentle stewards of those systems,” said Cohen. “As more and more people seek the kind of environmental solace of these incredible places, we’re loving them to death in some pretty fundamental ways.”

According to Cohen, one of the most significant issues facing the springs is that the Floridan aquifer is producing water with much lower oxygen concentrations than it used to. This results in less aquatic vegetation, a decrease in aquatic snails, which leads to an increase in algae, as algae is their primary food source.

“I think if you gave me $100 million and said, ‘Invest it in the things that you think are most important,’ I would put 80% of it into trying to understand that phenomenon and what we can do about it,” he said.

In other words, what are we doing to the aquifer that might impact the oxygen levels?

With no clear answer, Cohen speculates that the water that is removed from the aquifer alters its “plumbing”. This creates space for nutrient-rich water to fill the aquifer, serving as food for microscopic organisms that use oxygen, therefore depleting the aquifer’s oxygen concentrations.

Ichetucknee River [Credit: Steven Earl]

As scientists like Cohen search for answers under the surface, others are focused on what’s happening above the surface in Florida’s laws and policies that govern water use. That’s where the fight over the state’s “Springs Harm Rule” began.

The rule that sparked a battle

In 2016, Senate Bill 552, which included a section known as the Springs Harm Rule, was signed into law by then-Gov. Rick Scott. This added 30 newly designated “Outstanding Florida Springs,” to be protected under Florida’s water use permitting laws.

The bill also mandated that the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) adopt uniform rules for issuing water use permits that would help prevent harm from groundwater withdrawals.

“For eight years. They never did it. They never proposed a rule,” said Ryan Smart, executive director of the Florida Springs Council (FSC), a statewide advocacy organization based in Gainesville, Fla., that focuses on the protection of Florida springs.

In 2024, after years of inaction, the FSC sued FDEP, seeking an order compelling the state to establish water use rules as required by the law. The court ordered FDEP to propose the rule in late 2024.

“However, the rule that they proposed was identical to rules that were in place, not only today, but two years before,” said Smart.

This prompted strong public opposition and a new legal challenge from the FSC.

In May, Florida Administration Law Judge E. Gary Early dismissed the suit, finding that the newly proposed rules “meet the facial requirements established by the legislature,” adding that whether the rules governing water use permit harm to the protected springs “is a matter for consideration on a case-by-case basis.”

The Springs Council is appealing the dismissal. Its attorney, Doug MacLaughlin, said that Early interpreted the rules narrowly, focusing on the precise wording of the statute, an approach known as “textualism,” instead of what the rule was meant to achieve.

“Everything is textualist these days, but that doesn’t mean you just do away with common sense,” MacLaughlin said.

FDEP did not respond to requests for an interview with The Click. However, in May, a spokesperson for the agency told local news outlet WUFT that the ruling affirms its “authority to move forward with implementing enforceable criteria that will ensure meaningful protections for Florida’s springs.”

But activists like Smart have not lost hope.

“We’ve got the law that we need. We’ve got the system in place. All we need to do is for the agency to follow the law and enforce it,” he said.

Hope flows slowly

With the appeal filed, there is nothing more environmentalists can do but wait. “The appellate courts don’t have any deadlines, so it could be whenever they like. It could be quite a while,” said MacLaughlin.

In the meantime, though, the threats the springs face persist, and for some, watching the springs change over time has taken its toll. “It feels like watching a loved one slowly die of cancer,” said Earl, the retired park ranger.

Peebles, the artist, feels it’s a “grief process.” “It was like the death of this incredibly beautiful being,” she said. As far as the future of the springs is concerned, “Once we know a pattern, we’re supposed to do better. We’re supposed to learn more,” she reflected.

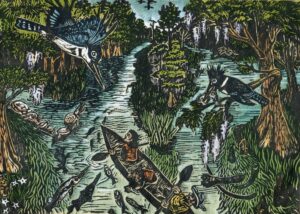

‘Canoeing the Itchetucknee’ by Leslie Peebles (linocut block print and watercolor) [Credit: Leslie Peebles]

“I feel like the absolutist position of some of the advocacy groups is often mostly theatrical to sort of create the space to enable discourse, to move in a direction, even if they don’t necessarily feel like everybody is being negligent,” he said. “But that language actually has consequences, because a lot of people then fundamentally believe that our government is not doing anything. We can argue about whether they’re doing enough.”

Doing enough could include adopting better agricultural practices, transitioning away from sprinkler systems, and incentivizing more sustainable environmental practices, he said. He adds that climate change should be factored into water-use permitting. If rainfall patterns change, then the permit process should “change with it.” In other words, if less water enters the aquifer, then less water should leave it.

Smart recognizes the multitude of challenges that lie ahead but believes the reward will be worth it.

“At the end of the day, when we win, and the court instructs FDEP to develop new, more protective rules, that will benefit all of the springs across Florida,” said Smart.

For those fighting this ongoing battle, this view of the future keeps them motivated. Florida’s springs have been a silent witness to the changes that have occurred in the landscape over the past 20 million years, and those who love them are unwilling to let their story end now.