Rachel Moore, Executive Director of Helen Day Art Center in Stowe, Vermont, 2020.

[Credit: Adriana Teresa Letorney]

(STOWE, Vt.) — In early 2019, Rachel Moore went on a school field trip with her daughter Lucy to Moravian Cabin, a roadside lodge for Stowe’s early ski tourists.

She was eager to learn more about the cabin built in 1935, and the people who owned it, including the namesake of the eponymous Helen Day Art Center in Stowe, which Moore runs.

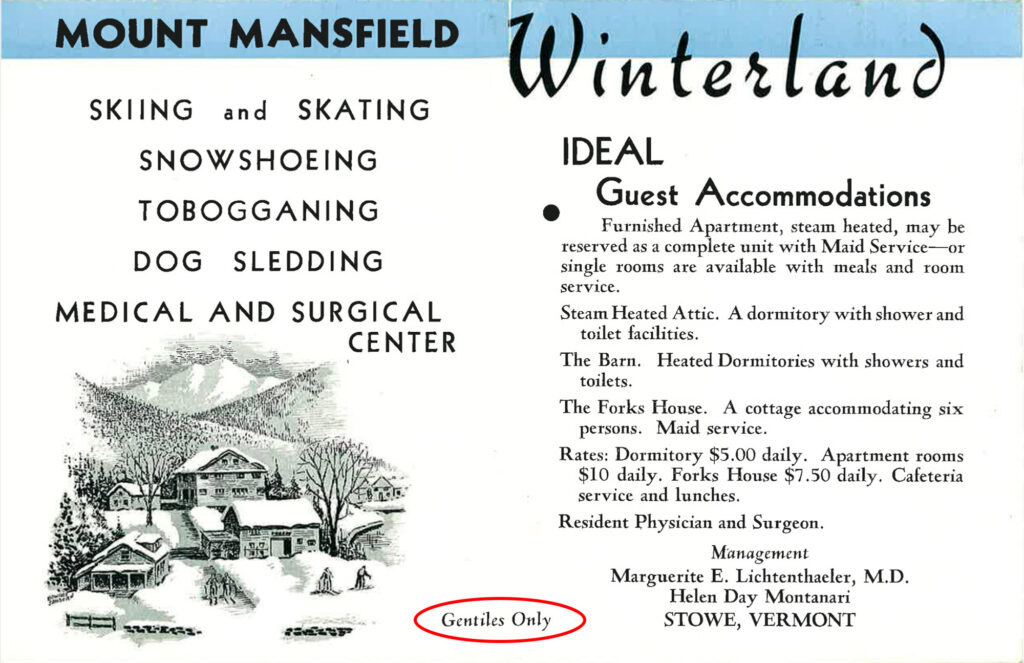

As Moore was learning about the roadhouse and its owners —Dr. Marguerite Lichtenthaler, her brother Frank, and her partner Helen Day Montanari— a guide handed an old brochure advertising the property in the 1930s. Beneath a hand-drawn picture of a snowy cabin and a list of ‘Winterland’ amenities are the words ‘Gentiles Only.”

Moore knew then that the rumors were true. Day and her partner Dr. Lichtenthaler, who left a bequest used to renovate the building that became the Helen Day Art Center— were engaged in anti-Semitic practices, not uncommon in Stowe and other parts of the country at the time. She also knew the center would have to address this history.

“The town itself was anti-Semitic and pushed lodging owners to not allow Jews in their accommodations,” she said. The ‘gentiles only’ restriction was possibly extended to other minority groups who lived in or came to the Town of Stowe during that time, she added.

Beyond the brochure, Moore has heard other stories which lead her to believe it was not the only instance of anti-Semitism by the couple and therefore needs to be addressed by the art center.

This 1930s marketing brochure ( exact date unknown) invited tourists to stay at the Moravian Cabin on Mount Mansfield in Stowe, Vermont. The cabin was owned and managed by Dr. Lichtenthaeler and Helen Day Montanari, who left a bequest to the town to build an art center and library. The brochure included the words ‘Gentiles Only” (marked here in red) restricting clientele to ‘gentiles’ or non-Jews only.

A statement released by the art center described Helen and her partner Dr. Marguerite Lichtenthaler as progressive women for their time, who fought for arts and culture in Stowe.

“We have discovered, however, that for all their forward-thinking, the women espoused deeply held antisemitic and racist beliefs.”

As a result. the center led by Moore announced it will be changing its name to reflect the current values. “We understand our responsibility to change the name in order to better reflect who we are as an organization, ” Moore said.

Day died in 1955 and efforts to reach family members of hers and Lichtenthaler for comment were unsuccessful.

The discovery of the brochure and more recent incidents of anti-Semitism in Stowe are prompting some residents to confront the past and to reckon with its history. Residents, organizations, and business owners are working to create systematic changes to foster diversity, empathy, equity, and belonging in the Stowe community.

“Changing the name is an opportunity,” says Diane Arnold, Chairwoman of the art and educational center. “With the rebranding of Helen Day, I foresee that in the next year or two, we will see some big changes.”

The center has hired a professional branding specialist with the support of a committee in its effort to choose its name. “We look forward to this as an opportunity to make clear our continued belief in inclusivity, diversity, and equity for all,” said Moore.

The Jewish Community of Greater Stowe responds

During a phone interview, Rabbi David Fainsilber of the Jewish Community of Greater Stowe (JCOGS) pointed that Helen Day Art Center did not have a history of discrimination or racism but that the people who helped initially fund the art center did have prejudiced views and practices.

“Stowe’s troubling history of restricting clientele at local lodging meant excluding Jews, people of color, and others from visiting the area and enjoying all that Vermont has to offer,” he said in a statement released by the art center.

“Coming to terms with and remembering history has long been a value of the Jewish community in combating today’s bigotry. Change is rarely easy. We are grateful to the art center for their forward-thinking, as they use the intersection of history and art as an inclusive, educational tool. May this serve as a moment of reflection for the society we wish to create and the legacies we choose to lift up.”—Fainsilber said.

Rabbi David Fainsilber of the Jewish Community of Greater Stowe (JCOGS), 2020. [Credit: Adriana Teresa Letorney]

Challenges the Jewish Community Faces

According to Fainsilber, with anti-Semitism, one of the main issues the Jewish community in Stowe and its neighboring towns come across are around security issues.

The synagogue works with local law enforcement to make sure that the Jewish community is secure and safe, especially from any hate groups, antisemitism, white nationalists, and supremacists.

Still, Fainsilber says there is a great sense of belonging. “As a minority in a very white, Christian state, there are day-to-day challenges, but for the most part, we feel a welcome part of the community.”

The Jewish Community of Greater Stowe (JCOGS) is the only synagogue in a radius of 30 miles, 2020. [Credit: Adriana Teresa Letorney]

About the Jewish Community in Vermont

According to the Pew Research Center, over 94% of Vermont residents are white, more than 54% are Christian, 37% are unaffiliated, and 2% of residents are Jewish.

Fainsilber says the Jewish community in Stowe consists of more than 200 families from across 15 neighboring towns. “ In these towns, there are dozens of churches, however, the Stowe synagogue is the only one in a radius of 30 miles.”

The synagogues in Montpellier, Burlington, and St. Johnsbury are the others closest to Stowe.

The Jewish community, according to Fainsilber, does a lot of outreach work both with the local community in Stowe and across the many towns, to let residents know that the Stowe Synagogue is a safe and welcoming place.

Although there is an increase in Jewish families in Stowe, the community is still a significant minority.

As a result, the synagogue has become involved with the school administrators to make sure that the Jewish students are supported, and feel a sense of belonging, especially within the community at large.

A problem of hate speech and anti-Semitism in schools

According to an article published on Stowe Reporter in 2019, “Jewish students in Vermont face a lot of harassment over their religion, according to faith leaders.” Simon Rosenbaum, then a student at Stowe Middle School, wrote an entry about anti-Semitism in school for U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders’ State of the Union essay contest. A finalist, Rosenbaum shared his experience at Stowe Middle School:

“I began wearing a yarmulke halfway through seventh grade. I remember weeks of emotional preparation for the snide remarks and lost friends that were sure to come. Before the morning bell had even rung, my kippah had already been grabbed and torn off. This was the result of the few Jewish kids in the school pretending that they weren’t Jewish for fear of retribution from their classmates.”

According to the article, only one member of the school board, Jim Brochhausen commented on Simon’s essay saying he didn’t believe the allegations. None of the other four school board members would comment. Instead, the reporter was referred to Tracy Wrend, the superintendent of Lamoille South Supervisory Union, who commented: “Behaviors that may be harassing, anti-Semitic or otherwise contributing to a learning environment” that’s not healthy for students or staff members “are not acceptable in our community and especially not in our schools.”

Saudia LaMont, Chair of R.E.A.L, The Racial Equity Alliance of Lamoille, 2020. [Credit: Adriana Teresa Letorney]

Fostering equity, inclusion and belonging

Many in the Jewish Community of Greater Stowe (JCOGS), including Fainsilber, have been active in creating R.E.A.L., the Racial Equity Alliance of Lamoille, a community coalition committed to building a safe, equitable, antiracist community, “where all can thrive regardless of the color of their skin, their ethnicity, religion, sexuality, gender, or any other aspect of identity.”

R.E.A.L. is led by a steering committee, which consists of the JCOGS and other community leaders of which Saudia LaMont is the chair. The group meets monthly to discuss issues and plan activities around youth, business and community engagement,

The coalition was formed in response to several incidents of racism and anti-Semitism in Stowe.

In 2018, LaMont said anti-Semitic graffiti with hate speech that included a swastika and an MS-13 gang symbol was found at Morristown’s People’s Academy High School’s softball field. At Stowe Middle/High School, swastika’s were being put in student lockers, and Jewish students were being harassed and bullied, according to LaMont. In 2018, the Burlington Free Press published a story about anti-Semitic graffiti found on a classroom table at Stowe Middle/High School.

“Some of the Jewish parents pulled their kids out of school because it was that severe,” she says, “The swastika on the field, I think was the last straw.” As a result, LaMont said the community came together and recognized there was a problem. R.E.A.L. was formed to build a safer community.

Mending a past to move forward

Fainsilber believes in the importance of fostering a deeper conversation amongst neighbors, one of understanding and belonging: “One in which we come to the place where people can appreciate that everybody chooses to be here belongs here.”

“Don’t underestimate how these tough conversations around equity, raise, and diversity can bring about change,” Fainsilber says.

Rachel Vandenberg, owner of Sun & Ski Inn and Suites, a modern roadside-inn in Stowe, and a member of the R.E.A.L business committee, 2020. [Credit: Adriana Teresa Letorney]

As a woman business owner of a modern roadside-inn, Vandenberg says: “I want all families to feel like they can come here and have a joyful experience and create lasting memories with their families.”

For LaMont, R.E.A.L tries to address antisemitism and racism through raising awareness and starting conversations, while simultaneously, “looking at the systems and the structures that are enforcing this and perpetuating the racial violence.” She says, “By focusing on all the aspects of where systems are involved, and engaging in those ways, that is how we are doing the work.”

She feels strongly that individuals and organizations have to ask themselves the hard questions like, how are we participating in and allowing this white supremacy culture to continue? And How are we subconsciously engaging and participating in this system that is causing further harm?

She says the first step is to assess, and the second is to acknowledge the problem.

“A name on a building or for an organization signals a model – someone we aspire to, honor and believe in,” Moore said about changing the center’s name to reflect its current values.

“While we must not forget our history lest we repeat it, we need to face it to move forward into a more inclusive future.”