(SARAJEVO, Bosnia and Herzegovina) — Ahmed Hrustanovic was seven years old when he was forced to leave his hometown of Srebrenica in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It was April 13, 1993, and the Bosnian war had already raged for over a year.

Just a day before, Serb forces who had besieged the city shelled a school playground, killing 74 people, most of whom were children.

The day he left, Hrustanovic climbed aboard a U.N. humanitarian convoy with his sister, his pregnant mother, and dozens of other women and children.

Hrustanovic’s father, Rifet Hrustanovic, was 29 years old at the time. Like thousands of other Bosniak men in Srebrenica, he was forced by Serb forces to stay behind.

That April day in 1993 was the last time Hrustanovic saw his father.

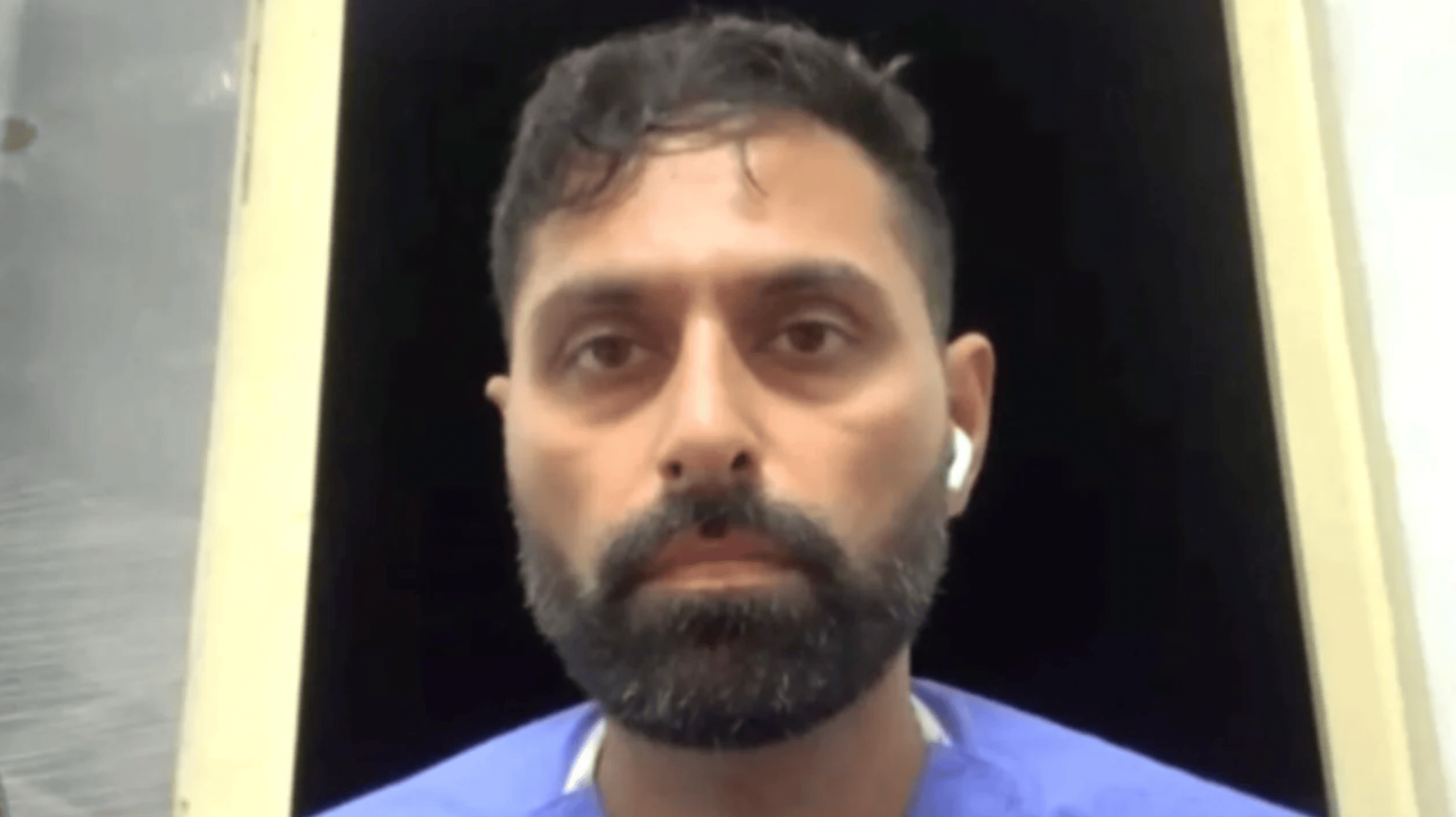

“My father ran after the convoy for as long as he could,” Hrustanovic told The Click, recounting the day. “He was in tears, pulling his hair. I was also crying, and the women and children around me. It was chaotic. I just knew in my heart that I’ll never see him again.”

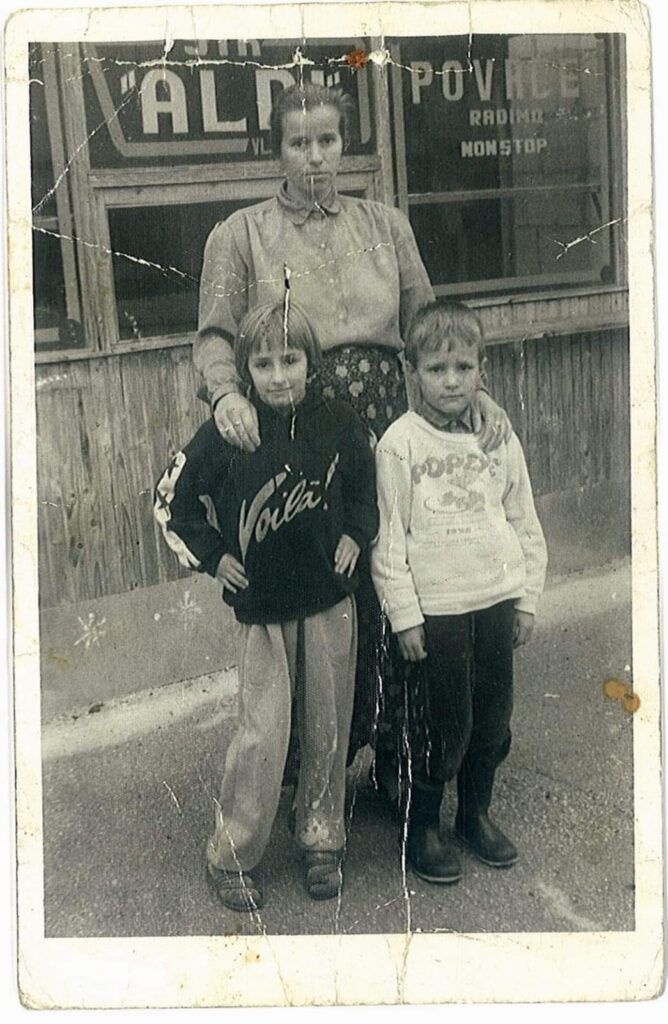

Ahmed Hrustanovic (right), his sister Refija (left), and his pregnant mother Beguna (back), after they escaped Srebrenica in 1993. [Photo courtesy of Ahmed Hrustanovic]

When the war erupted in Bosnia in 1992, Hrustanovic was six years old.

The majority of villages surrounding Srebrenica, including Miholjevine, became constant targets of Serbs’ shellings.

“I remember asking my father about the gunshots that were sounding non-stop in the distance. He would tell me not to worry, that someone was getting married, and that the arms were fired as a form of celebration. But I could feel in his voice that something was wrong,” Hrustanovic said.

In August 1992, a grenade almost killed Hrustanovic’s mother and sister, and his father decided that it had become too risky to continue their lives in the village.

By the beginning of 1993, they joined other families in and around Miholjevine who had found their refuge in Srebrenica.

Named after Bosnia’s word for “silver,” which the town is rich in, Srebrenica had a pre-war population of approximately 7,000 people, close to 75 percent of them Bosniaks. That number amounted to nearly 40,000 people during the first year of the war.

“To this day, I remember 1993 and those horrific scenes upon our arrival in Srebrenica,” Hrustanovic recounted.

“I have never seen so many people in one place in my life. It felt like the whole world descended upon those streets: women, children, elderly — so many of them. People were burning plastic in order to cook food. Even today, after so many years, I still can’t stand that smell,” he said.

Hrustanovic’s family had settled in one of the houses near Srebrenica’s primary school. The massacre that took place in the school’s playground in 1993 prompted the U.N. Security Council to declare Srebrenica and five surrounding towns and cities as “safe zones.” But the population, shaken by the event, no longer felt safe in the town.

The house in Srebrenica (far middle) where Hrustanovic lived with his family in 1993. Hrustanovic never gathered the courage to visit the house again, despite returning to the town in 2014. [Photo courtesy of Ahmed Hrustanovic]

“My father came rushing towards the convoy, all covered in dirt from helping bury the children from the massacre of the day before. He squeezed us in on top of the convoy with other women and children, hoping we would manage to leave Srebrenica,” Hrustanovic said.

“I held onto my mother’s skirt as a Serb soldier jumped onto the vehicle demanding to hand over any money and gold. My mother quickly hid her wedding ring in one of my sister’s boots — the only memory we have left of my father from that day”.

Two years after Hrustanovic left Srebrenica, his father was killed by Serb forces along with over 8,000 other unarmed Bosniak men and boys. His remains were spread across three separate mass graves. Another 30,000 women, children, and elderly were forcibly displaced from Srebrenica, and many women and men were raped.

Hrustanovic lost all of his adult male relatives in the genocide, over thirty of them, including both of his paternal and maternal grandfathers and uncles.

For most of his life, he lived in different cities in Bosnia. But in 2014, he decided to move back to Srebrenica. Today, he works as an imam in one of the four reconstructed mosques in the town which Serb forces leveled to the ground during the war.

Hrustanovic said that for many years he blamed himself for not doing something to save his father.

He never spoke to his siblings about their loss, and never asked his younger brother — who was born shortly after their departure from Srebrenica in 1993 — what it was like to grow up without a father.

“Perhaps it was a mistake that I never addressed this with my siblings, particularly with my brother who never had a chance to meet our father,” Hrustanovic said. “But in all these years, I could never gather the courage to open that subject with them.”

Ahmed Hrustanovic (back) with his older sister Refija (right), younger brother Enis (front), and a cousin (left) in front of a refugee house in Bosnia’s city of Tuzla, a year after the end of Bosnia’s 1992-95 war. He and his siblings still had hopes that their father would return. [Photo courtesy of Ahmed Hrustanovic]

The peace accords that were signed in Dayton, Ohio in 1995, ended the war, dividing the country into two entities: a Bosniak-Croat-majority Federation, and a Serb-majority Republika Srpska.

“This is really a litmus paper of the reality that Bosnia is in as a country today. The Dayton peace treaty is part of that reality, where the perpetrators of genocide were officially rewarded with a territory where they committed the genocide, while the victims were punished,” Mesic said.

A Srebrenica survivor himself, Mesic fears that history will repeat itself.

“It’s unthinkable that after a genocide, ethnic cleansing, rape, and systematic concentration camps, those who committed the crime get to keep that land. I fear such a world,” Mesic said.

Mesic said that he also fears that the war that erupted in Ukraine in February, combined with Bosnia’s political insecurity and recent secession narratives by Bosnian-Serb politicians, could cause a new wave of wars in Europe, something he said Bosnia is particularly vulnerable to.

According to Mesic, this could directly affect Srebrenica, which now forms part of Republika Srpska’s entity.

But despite fears of war, Hrustanovic said that he doesn’t plan to leave Srebrenica anytime soon, where he now lives with his wife and their five children.

“I’ve found my peace in Srebrenica, near my father’s grave. This is my only home. The idea that this town could be taken by the same people that killed my father is something I can’t even begin to imagine,” Hrustanovic said, adding that he named his youngest son after his father.

“I still feel a sting in my heart whenever I call [my son] by my father’s name. I can’t bear the idea that he might face the same fate in the future.”