(FORT BLISS, Texas) – The brutal murder of U.S. Army Spc. Vanessa Guillen made national headlines with the country turning its attention to the culture of sexual harassment and sexual assault on the Fort Hood installation.

Similar stories at other Army bases flew under the radar. Stories such as Pvt. Marriah Pouncy and Pfc. Asia Graham, whose deaths occurred on Fort Bliss after reports of sexual assault, did not garner as much attention.

U.S. Army Veteran Mandy Crawford shares her story as a survivor of sexual assault in Fort Bliss, Texas. [Credit: Staff Sgt. John Onuoha/DVIDS]

Mandy Crawford, an Army veteran, shared her story with a military website about recovering from sexual assault as a young soldier in Fort Bliss, Texas.

“He took me to his room, and I just remember telling him, ‘Hey, I have a boyfriend don’t touch me,’ and he went the whole …” Crawford recalled before falling silent. “When that rape happened, it’s so hard to even say that word; I felt like I was going back into a giant hole just falling. I just thought if I died everything would just go away.”

Crawford was one of hundreds of soldiers assaulted while stationed at Fort Bliss, according to a 2021 report from the Research and Development (RAND) Corporation. The report includes a survey of active Army soldiers who experienced sexual assault and sexual harassment between August 2017 and July 2018. It identified Army installations with the highest reported incidents of sexual assault. The top three, in order, were Fort Hood and Fort Bliss in Texas and Fort Stewart in Georgia.

While Fort Hood attracts much of the media’s attention with its highest incidents of sexual assault, Fort Bliss holds the second highest sexual assault incidents out of all installations.

According to the RAND report, during the year-long period studied, Fort Bliss recorded 274 sexual assault incidents among 3,609 women, a 7.6% sexual assault risk for women on base. Put another way, one in every 13 women on base were at risk for attack that year. The average total risk to all women in the Army in 2017-2018 was 5.8%, about one-fourth lower than Fort Bliss.

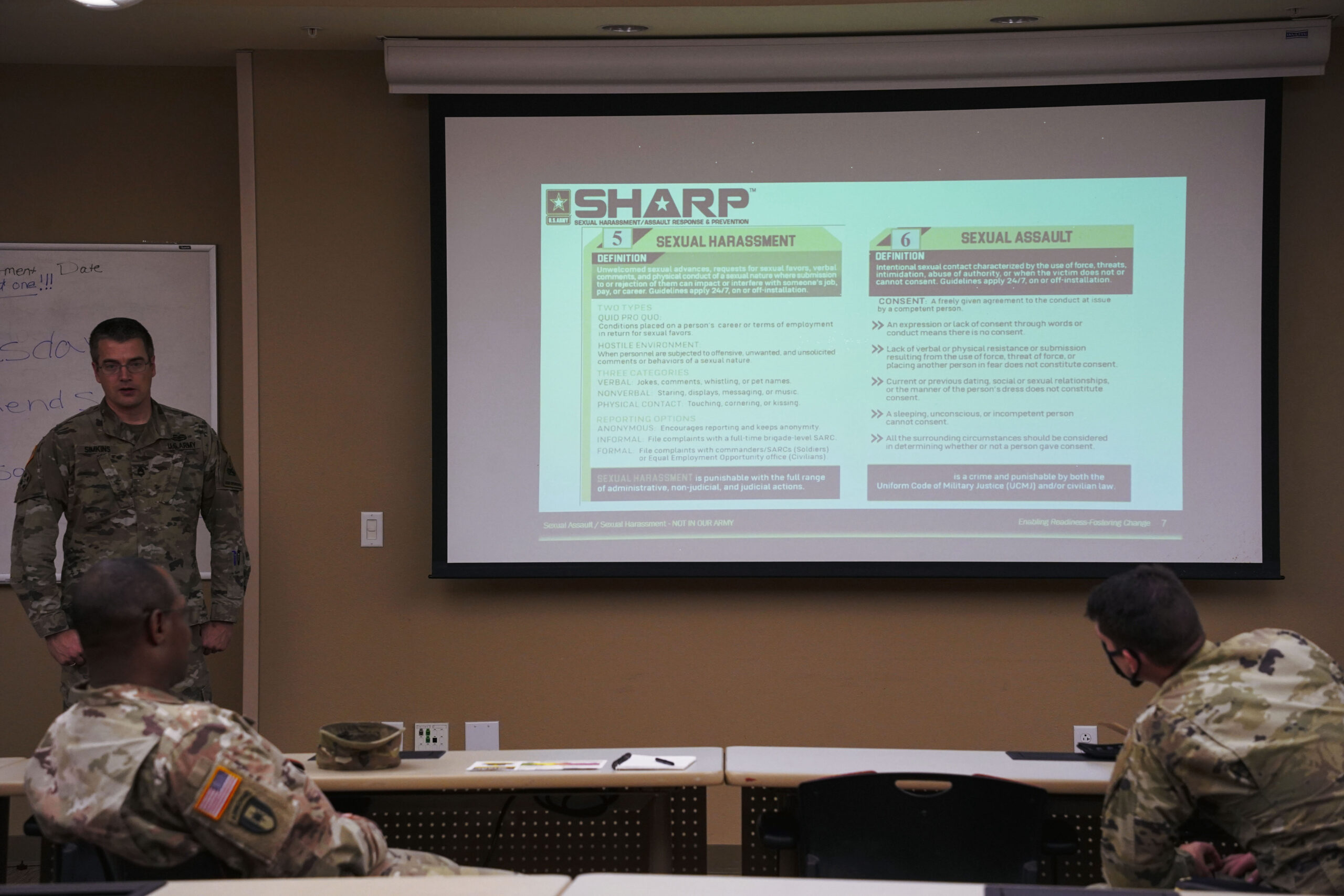

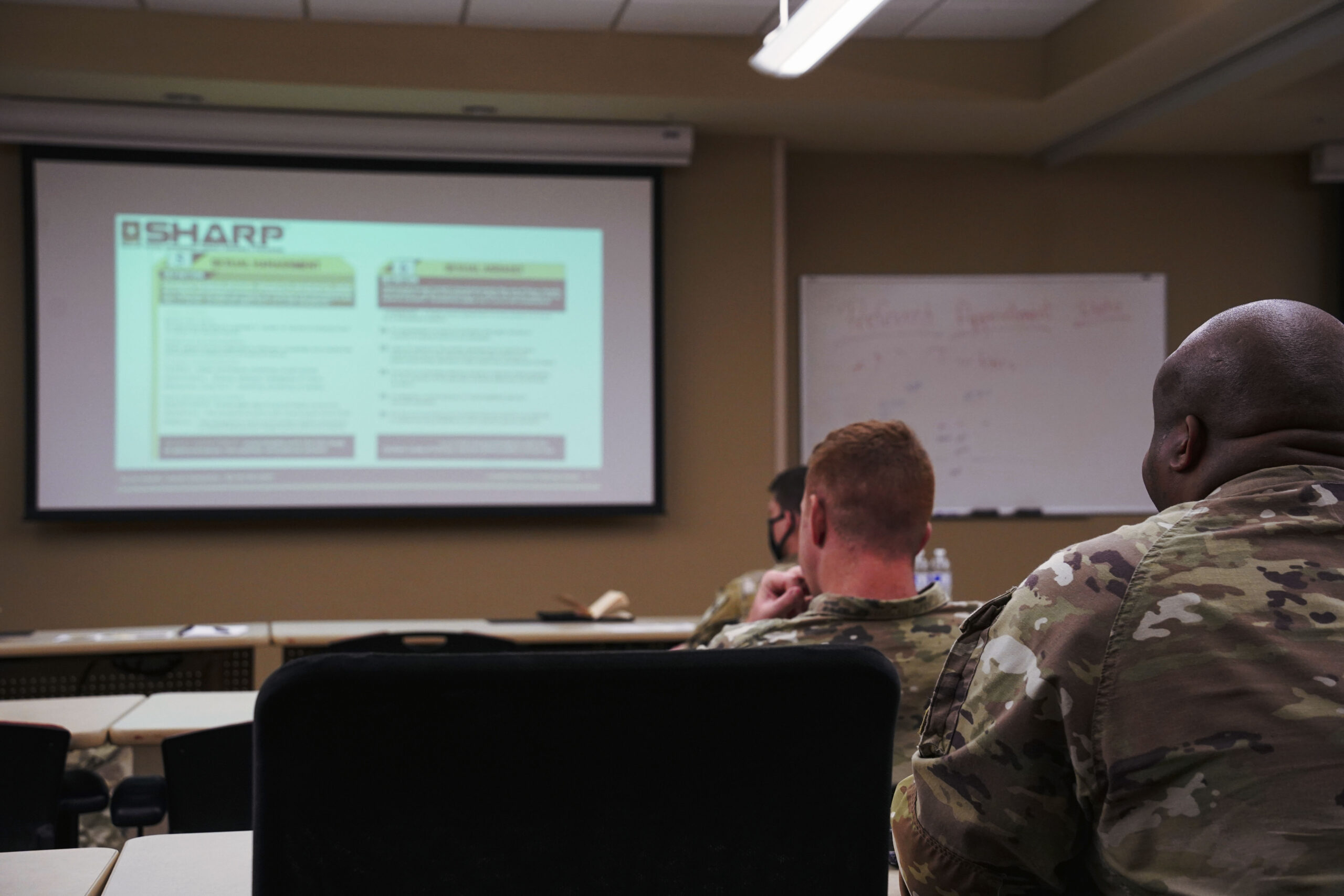

These stark facts were apparently unfamiliar to Fort Bliss leaders with the 1st Armored Division Artillery (DIVARTY), based on a recent sexual assault prevention training.

‘There is no unit that is in the green”

U.S. Army Sgt. 1st Class Joshua Simkins, the brigade sexual assault response coordinator with the 1st Armored Division Artillery, leads he train-the-trainer session as part of the Sexual Harassment/Assault Response Prevention program the with the 1st Armored Division Artillery in Fort Bliss, Texas, March 17, 2022. [Credit: LaShic Mondrell]

“[The] majority of your mid-level leaders think everybody is green and good to go,” said Sgt. 1st Class Joshua Simkins, the brigade sexual assault response coordinator with DIVARTY, during his “train-the-trainer” session on March 17. “I give more of what the real picture is and explain to them why it exits that way, that there is no unit that is in the green. Even the best units are in the yellow. Most units are hanging out more towards bright orange and occasionally dipping in the red.”

Each year, Army leaders implement prevention training with the goal to decrease sexual assault. Each unit’s brigade sexual assault response coordinator “trains the trainer,” preparing leaders to conduct training as sexual assault response coordinators and victim advocates themselves.

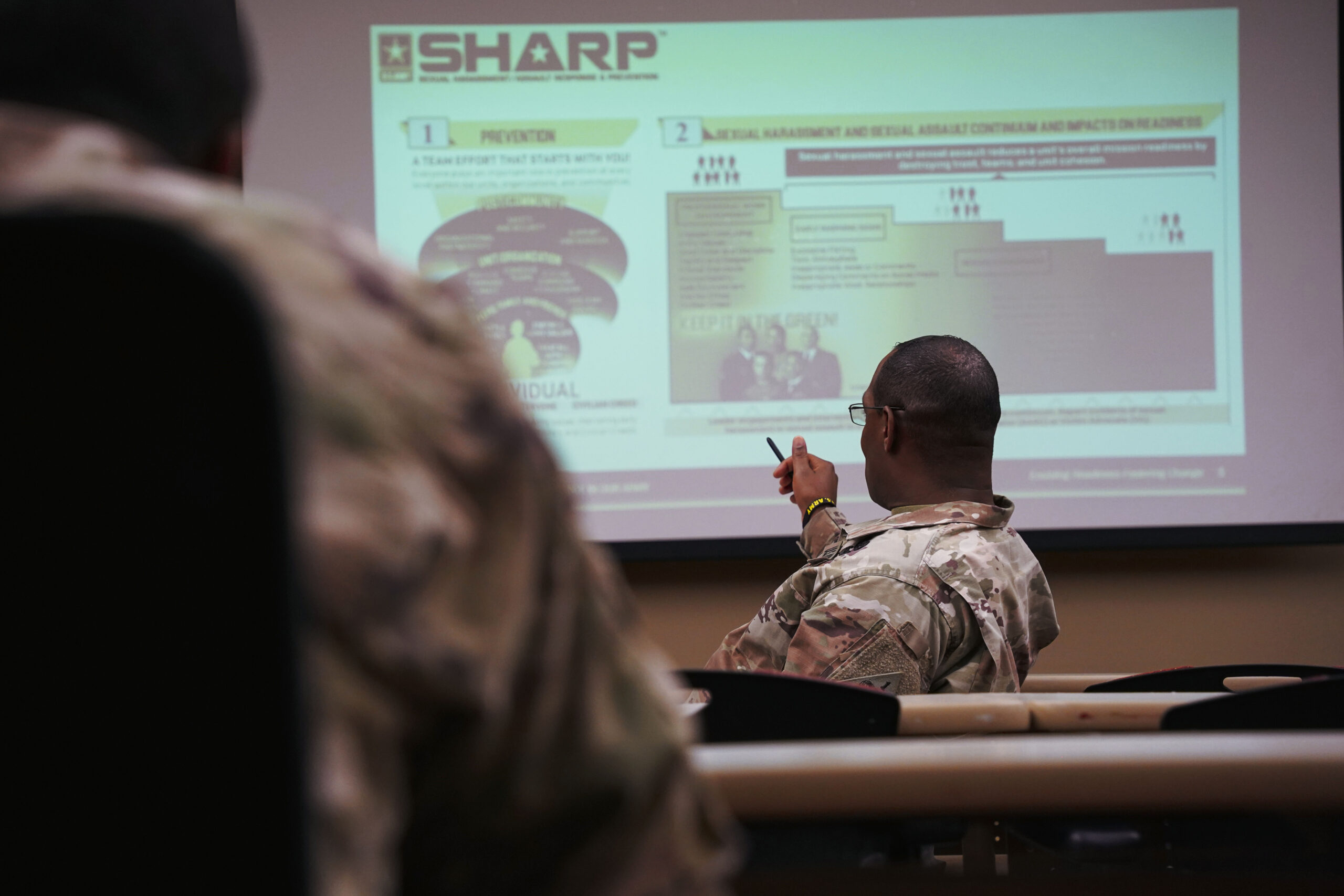

“Moving on to block two, and this is where we really like to put a lot of attention on when you’re discussing this with your soldiers,” Simkins said during the session he led. “Let’s say at company level, where do you feel your companies are on this scale [on the] sexual harassment sexual assault continuum?”

U.S. Army Sgt. David Cordova (left) and Sgt. Jacob Lang (right) attend the train-the-trainer session as part of the Sexual Harassment/Assault Response Prevention program the with the 1st Armored Division Artillery in Fort Bliss, Texas, March 17, 2022. [Credit: LaShic Mondrell]

A few participants left their seats to grab the continuum handout with the green, yellow, orange, and red awareness scale, while the rest processed the question further, staring at the slide presentation ahead of them.

Initially, none of the leaders expressed any knowledge of sexual assault, until one spoke out.

“I would say most units in the Army right now are floating in the yellow to reddish area; that’s where we are sitting right now,” said Master Sgt. Christopher Primrose, a human resource and retention noncommissioned officer with DIVARTY. “However, the only way we can get in the green is if every unit in the Army does not have a sexual assault case. Realistically speaking, that’s where we all are.”

This raises the question: If Army leaders are unaware of the research or of incidents within their ranks, how can they address sexual assault?

How are Fort Bliss leaders addressing sexual assault?

Simkins and his counterparts describe their day-to-day roles within the Sexual Harassment/Assault Response Prevention (SHARP) program as working to decrease sexual harassment and assault incidents by increasing leader awareness.

“We definitely train the soldiers on what consent is, try to highlight the need for communication, and understanding how to communicate in regards to sex,” said Simkins describing the SHARP program. “It’s going to require a lot of lower-level leaders communicating with their soldiers and actually instilling the culture we would like to have into them.”

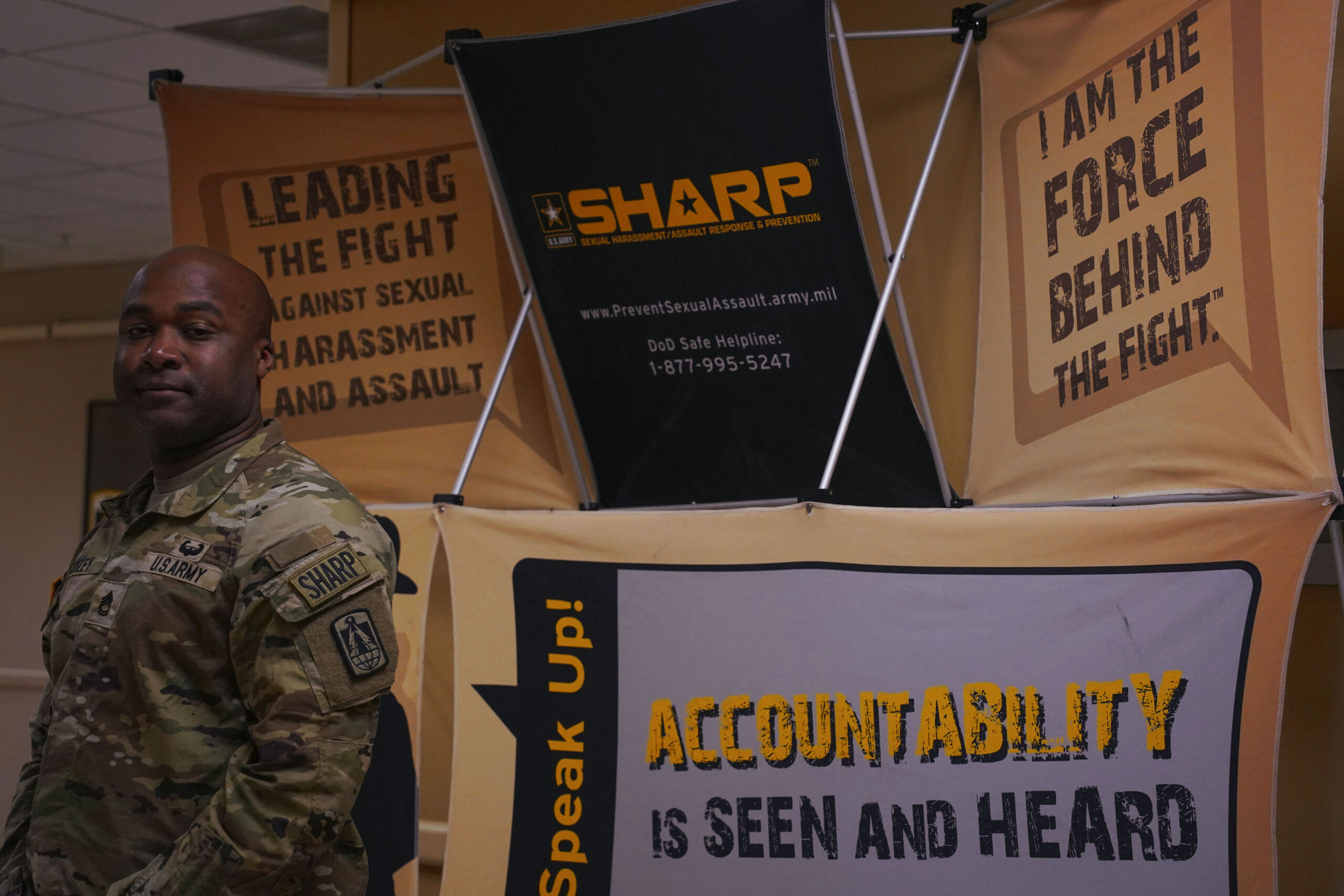

U.S. Army Sgt. 1st Class Joshua Simkins, the brigade sexual assault response coordinator with the 1st Armored Division Artillery, stands outside of the Sexual Harassment/Assault Response Prevention office in Fort Bliss, Texas, April 6, 2022. [Credit: LaShic Mondrell]

Simkins seeks to gain trust through the SHARP program, in part, by posting sexual assault myth-buster flyers and infographics outlining punitive actions for violations at Fort Bliss.

“Until we can get the victims of sexual assault to feel more comfortable coming forward to us, it’s harder to deal with it because we don’t know who,” said Simkins stating that their goal is find out who the offender is. “We’ve been trying to instill trust into our program because there is not much trust in the SHARP program.”

With changes to the Uniform Code of Military Justice to protect victim rights along with the addition of the Catch a Serial Offender (CATCH) program, Simkins further discusses their prevention measures.

According to Simkins, the CATCH program works to bridge the gap between restricted reporting, in which the victim does not notify law enforcement, and unrestricted reporting, in which involves law enforcement. Details on what to do and how to report a sexual assault are available on the SHARP’s website.

“The CATCH program is designed to catch serial offenders,” said Simkins. “It was initially designed for restricted cases so that the victims could enter identifying details of the offender, and then, if the offender comes up in multiple cases or been reported for other incidents, it would give us what we would call a hit.”

Simkins is then notified that the alleged offender was involved in another case. He would next contact the victim to let them know that the offender could be involved in other sexual assaults. This allows the victim to make an unrestricted report to protect others and punish the offender.

U.S. Army Staff Sgt. 1st Class Almont Ashley, the victim advocate with the 86th Expeditionary Signal Battalion, 1st Armored Division Artillery, stands by the Sexual Harassment/Assault Response Prevention posters and infographics in Fort Bliss, Texas, April 7, 2022. [Credit: LaShic Mondrell]

Sgt. 1st Class Almont Ashley, a victim advocate with the 86th Expeditionary Signal Battalion, DIVARTY, said that the military code changes increased safety and seriousness of reporting to leadership, mentioning that the base works with the El Paso District Attorney, Yvonne Rosales, as a liaison to improve the SHARP program and Criminal Investigation Division cases for the Fort Bliss and El Paso areas.

Last year, Ashley said, they added “the Ambassador program, which is where junior soldiers from the rank of E-1 to E-5 and junior officers, first and second lieutenant, come and learn basically a more compressed version of my SHARP training.”

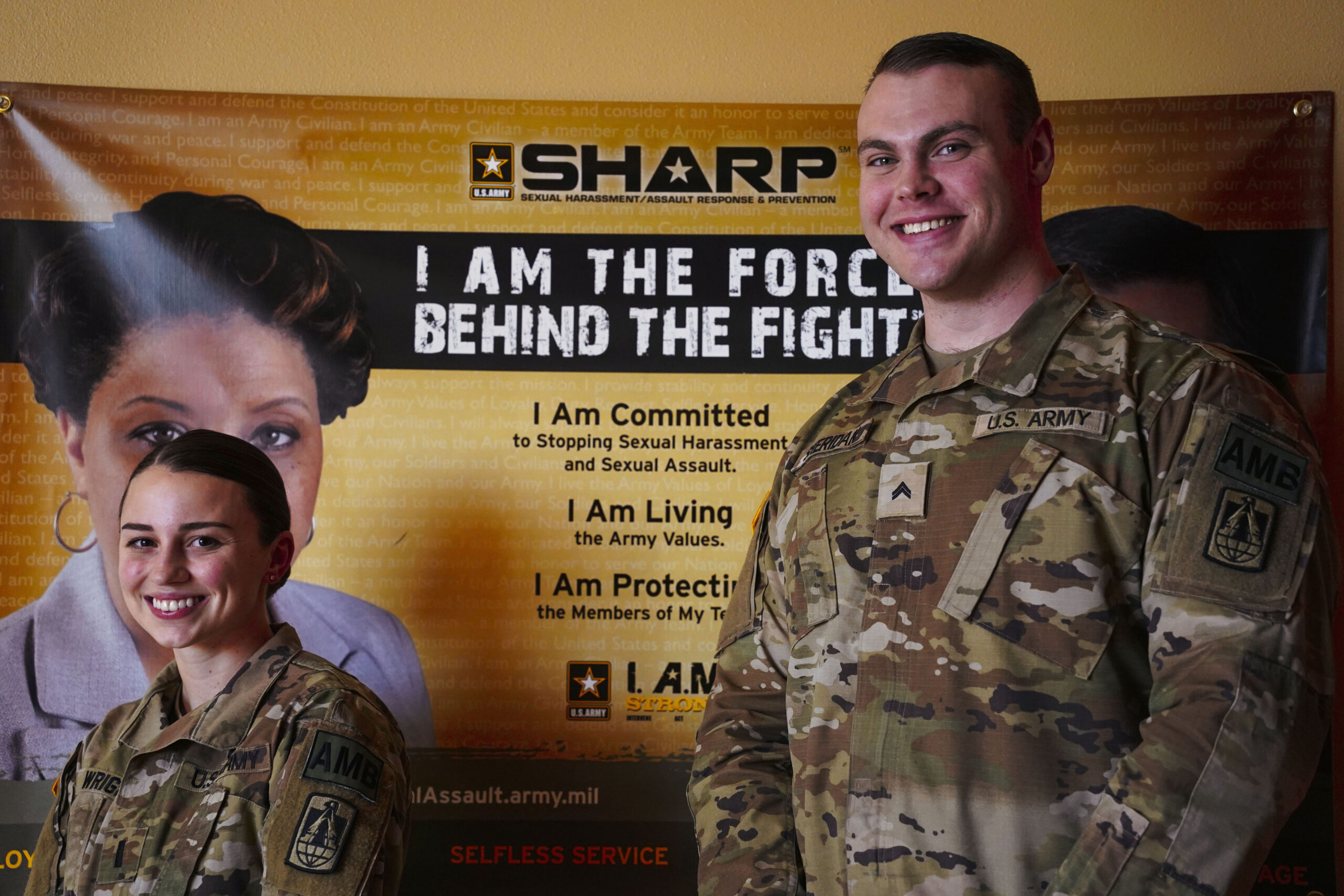

Ashley’s newest Ambassador program graduates are Cpl. William Sheridan and 1st Lt. Aidan Wright, both of whom serve as the liaison between the unit’s soldiers and the sexual assault response coordinators and victim advocates.

“I will approach a lieutenant colonel if I feel like they are wrong,” said Sheridan. In doing this, he said, “My rank goes out of the window; because in a situation that involves this, my consideration for mental health outranks this uniform. I won’t stand for injustice in that sense. I will tell just about anybody, toxic leadership or otherwise, that they’re not in the right if they’re not.”

U.S. Army 1st Lt. Aidan Wright (left) and Cpl. William Sheridan, sexual assault prevention ambassadors with the 86th Expeditionary Signal Battalion, 1st Armored Division Artillery, stand in front of a Sexual Harassment/Assault Response Prevention poster in Fort Bliss, Texas, April 7, 2022. [Credit: LaShic Mondrell]

Wright’s work is motivated by her own experience with sexual harassment.

“I’ve experienced it myself, on missions and back here in garrison,” said Wright. “Now that I feel like I have a voice, [I want] to shut it down for people who don’t have a voice. When I was a second lieutenant, a major said something to me, but I didn’t say anything to them. I try to encourage people to do the same and to stand up against harassment because you will see how much you can get away with until it goes too far. Trying to stop it early is my goal.”

While the U.S. Army is trying a new approach, how the approach will impact the numbers of sexual assault incidents is too early to be determined.

The sexual assault correlations that Fort Bliss leaders are neglecting

Currently, the Army does not psychologically evaluate soldiers during their initial entry into the Army via the Military Entrance Processing Station.

Psychological evaluations can be a starting point to know what contributing mental factors lead to the culture of sexual assault upon a soldier’s initial entry rather than waiting until a soldier’s arrival at a first-duty station such as Fort Bliss.

“I feel like they spend more time asking if your recruiter lied,” said Sheridan. “I feel like it would be much better time spent if they vet [soldiers].”

U.S. Soldiers discuss sexual assault continuum during the train-the-trainer session as part of the Sexual Harassment/Assault Response Prevention program the with the 1st Armored Division Artillery in Fort Bliss, Texas, March 17, 2022. [Credit: LaShic Mondrell]

Fort Bliss also has the second highest sexual harassment incidents worldwide.

“Notably, sexual harassment is more common than sexual assault in the Army, but our results also showed that the risk of sexual harassment is highly correlated with the risk of sexual assault,” the RAND report reads. “Thus, bases with high sexual assault risk have high sexual harassment risk, and those with low sexual assault risk have low sexual harassment risk.”

The Army as a whole is considering adding sexual assault prevention as a military occupation specialty (MOS), according to Ashley.

“About a year and half ago, I first heard about them changing it into a MOS,” he said. “I believe it will be beneficial, but at the same time, the selection process needs to be strict.”

Ashley added that the selection process should prevent offenders from being a part of it, that it should be for the ranks of staff sergeant and up for the enlisted and 1st lieutenant and up for the officers, and that there should be a probation period before a soldier can obtain the MOS permanently.

Low conviction rates exacerbate the problem

Staff Sgt. Timothy Racki, a musician and victim advocate with the 1st Armored Division Band, spoke about the reported low conviction rates as another problem in combatting sexual assault at Fort Bliss.

Low conviction rates plague many Army installations. Courts-martial dropped by 69 percent from 2007 to 2017 with commanders opting for milder punishments for offenders such as deductions in rank or administrative discharges, according to the New York Times. An inquiry on the alleged low conviction rate of sexual assault cases at Fort Bliss was submitted to the Office of Staff Judge Advocate (OSJA). However, the OSJA declined to respond.

U.S. Army Staff Sgt. Timothy Racki, victim advocate and musician with the Headquarters and Headquarters Battalion, 1st Armored Division Band, stands next to building unit guide-on in Fort Bliss, Texas, April 7, 2022. [Credit: LaShic Mondrell]

“That sounds normal,” said Racki of the conviction rates. Asked why, he said, it’s “what comes out in legal, and if it can’t be proven, then it can’t be proven. It can be very hard to prove sexual assault, especially something that happened between two people, and no one else was there.”

Crawford added that her offender was never convicted and how soldiers can get away with crimes such as sexual assault in spite of the many Army regulations and UCMJ laws against it.

“Another thing I want to bring up is it’s not even about me. It’s the person that raped me. He transferred, and then, he did the same thing,” said Crawford describing how her offender went on to sexually assault civilians, as well. “How come nobody checked on him? Is that okay? Why have all of these rules, and no one is following them? What’s the point? That’s what frustrated me. People get away with things and don’t get [held accountable] for it.”

Outside experts such as Protect Our Defenders work to reduce sexual harassment and sexual assault across the military. The organization’s reports show how military branches such as the U.S. Army fail with misogyny as the root cause of sexual harassment and sexual assault.

“Inferior views of women certainly play a role,” according to the Protect Our Defender study. “A majority of women interviewed cited that the single most important thing the military could have done to keep them in service was to listen to them, believe their experiences, and provide them the support they needed to get back to the job after a situation of assault or harassment.”

U.S. Soldiers discuss reporting procedures for sexual harassment and sexual assault during the train-the-trainer session as part of the Sexual Harassment/Assault Response Prevention program the with the 1st Armored Division Artillery in Fort Bliss, Texas, March 17, 2022. [Credit: LaShic Mondrell]

The SHARP program and the Fort Bliss legal office and organizations like Protect Our Defenders operate mutually exclusively from the other. Red tape needs to be removed for a collaborative effort between these organizations to decrease sexual assault incidents.

The Department of Defense recognizes April as Sexual Assault Awareness and Prevention Month (SAAPM). Each unit hosts observances to spread awareness and prevention measures.

“My role in regards to SAAPM this year is encouraging the company command teams to create their awareness observances,” said Ashley, adding that his unit will do a morning ruck march during physical training to observe how sexual assault is not just a burden for one, but for all.

Ashley’s idea highlights that it is important not to reduce a sexual assault victim to a statistic. The sexual assault of even one person also harms their loved ones, forever changing the lives of not only the victim but also up to hundreds of people who are close to the victim.

In thinking of the many people sexual assault affects, the hope is that Fort Bliss leaders will improve their prevention efforts toward an Army installation in the green, free of sexual assault.

![U.S. Army sexual assault incidents versus Fort Bliss sexual assault incidents. [Credit: LaShic Mondrell] sexual assault prevention in Fort Bliss, Texas](https://theclick.news/wp-content/uploads/cache/2022/05/SA-2-Infographic/2306503085.png)

![Correlations that increase sexual assault incidents according to the Research and Development report. [Credit: LaShic Mondrell] sexual assault prevention in Fort Bliss, Texas](https://theclick.news/wp-content/uploads/cache/2022/05/SA-3-Infographic/999080766.png)

![Where, when, and how sexual assault incidents occur according to U.S. Department of Defense. [Credit: LaShic Mondrell] sexual assault prevention in Fort Bliss, Texas](https://theclick.news/wp-content/uploads/cache/2022/05/SA-4-Infographic/2929356870.png)

![“Train-the-trainer” sexual assault prevention presentation: prevention levels and continuum. [Credit: U.S. Army] sexual assault prevention in Fort Bliss, Texas](https://theclick.news/wp-content/uploads/cache/2022/05/Slide5-scaled/2660995360.jpeg)

![“Train-the-trainer” sexual assault prevention presentation: healthy boundaries and bystander intervention. [Credit: U.S. Army] sexual assault prevention in Fort Bliss, Texas](https://theclick.news/wp-content/uploads/cache/2022/05/Slide6-scaled/3849219350.jpeg)

*Editor’s Note: LaShic Mondrell, the author of the report, is a soldier with DIVARTY who worked as a sexual assault prevention coordinator prior to joining the U.S. Army.

![Sexual assault incidents in Fort Bliss, Texas by gender. [Credit: LaShic Mondrell] sexual assault prevention in Fort Bliss, Texas](https://theclick.news/wp-content/uploads/cache/2022/05/SA-1-Infographic/219501453.png)

![“Train-the-trainer” sexual assault prevention presentation: sexual harassment and sexual assault definitions. [Credit: U.S. Army] sexual assault prevention in Fort Bliss, Texas](https://theclick.news/wp-content/uploads/cache/2022/05/Slide7-scaled/3535555705.jpeg)

![“Train-the-trainer” sexual assault prevention presentation: sexual harassment and sexual assault reporting process. [Credit: U.S. Army] sexual assault prevention in Fort Bliss, Texas](https://theclick.news/wp-content/uploads/cache/2022/05/Slide8-scaled/241918855.jpeg)