(NEW YORK) – On a wet, rainy fall morning, Nina Lai kissed her 8-year-old daughter, Olivia, goodbye as she left for school. She put a leash on Otto, her black and brown German Shepherd, and left for a leisurely walk. Just one year ago, her stressful, hectic mornings were filled with urgent emails and last-minute meetings before she resigned in frustration over diversity programs.

For almost 20 years, Lai, now 38, navigated the corporate world with companies from Singapore to Dubai to London. In the fall of 2020, she landed a new job in San Francisco as global director of internal communications at Benefit Cosmetic, which was expanding its diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives. They also launched employee resource groups (ERGs) for career development.

With high hopes, Lai joined the company’s ERG for Asian-identifying employees. Her goal was to break through the barriers that impact Asian American women in corporate America, including the “bamboo ceiling” and the model minority myth. The bamboo ceiling refers to the discrimination they face; the model minority myth portrays them as inherently high-performing and successful.

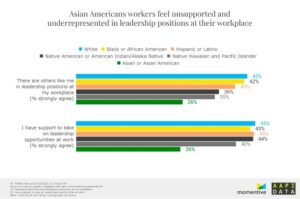

Lai said that although almost half of Asian American women had college degrees–compared to 31% of Whites, 18% of Blacks, and 13% of Hispanics–they weren’t even included in some of the DEI programs. Her company participated in a mentorship program for young Black women but did not have a similar offer for Asian American women.

Lai was surprised to find that she was the only Asian American woman out of 200 directors, making her feel like a token hire, especially considering the company’s consumer base. Asian American women spend 22.75% more annually on beauty products than the average U.S. buyer.

The Power of Asian American and Pacific Islander Beauty Shoppers.

When Lai asked HR during a leadership meeting why there were not more women of color in senior roles, she was told, “People of color don’t tend to apply for higher-level roles. Or they tend to do better in entry-level roles or admin roles.”

Instead of addressing her concerns, Lai was instructed to focus on external messaging on social media, like posting about solidarity with Black Lives Matter, Stop AAPI Hate and Pride movements. “It was very much about, let’s just show our consumers that we’re supporting these things,” she said, noting it felt performative. “But there was not a lot of work being done internally to advance employees.”

After taking a leave of absence and realizing that the resource group benefited the company’s public image more than its employees, Lai resigned from both the ERG and Benefit. “All the gaslighting, I couldn’t do it anymore. It just felt really wrong,” she said.

Lai’s experience is common for Asian American women who join their company’s employee resource groups hoping for a shot at the C-suite, said Karen Loong, executive director of the Asian American Professionals Association (AAPA). While the resource groups can help bolster a company’s public image and offer networking for their employees, they often lack the infrastructure to deliver on employees’ expectations.

Fewer than 1% of Asian American women occupy executive positions, compared to 22% of White women, 1.6% of Hispanic and Latina women, and 1.4% of Black women. “Breaking the bamboo ceiling requires resilience, strategic planning, and a supportive network,” Loong said, pointing to the crowd of people around her. She smiled proudly as she scanned the hotel ballroom in Pasadena, CA, where 300 AAPA members gathered for their annual fundraising gala in November.

Women in the Workplace 2023, McKinsey & Company and LeanIn.org

AAPA can help companies with a tailored strategy “addressing specific gaps identified by individuals, ERGs, or organizations. Whether it’s offering specialized workshops, expert speakers, mentors, or resources to navigate cultural biases,” Loong said.

Her advice to Asian American women is to “network extensively, both within and outside your industry, and consider joining nonprofit boards to gain valuable leadership experience.”

AAPA 2023 Gala. Credit: Jannelle Andes

Networking outside her company – not an ERG – was the approach taken by Yili Dolan, a Chinese American woman and managing director for State Street. Fortune 500 companies have spent billions of dollars on DEI initiatives and employee affinity programs. However, Dolan hadn’t “seen much of how ERGs have been used to promote Asian American women.”

Dolan participated in the McKinsey Asian Executive Leadership Program, a six-month course that focused on topics like how to combat Asian stereotypes in the workplace. They tackled issues like the perpetual foreigner. This perception views Americans of Asian descent as outsiders and not ideal leaders for American corporations.

Pan-Asian affinity groups also perpetuate the stereotype that Asians are all from the same background. “Company ERGs don’t really look at the nuances between where employees were brought up,” she said. “If you’re doing these broad-stroke programs, you’re not addressing the specific needs of that community.”

As she sat alone in an empty boardroom, Dolan’s almond-shaped brown eyes clouded over with sadness. She sighed and said that the most common stereotype is that Asian American women are quiet and often not taken seriously in positions of authority. “With the McKinsey program, they encouraged us to become a stronger leader, not only a person who can work really hard. This mindset will help us and the next generations to become leaders.”

Agnes Greenidge, of Panamanian and Chinese descent, has been trying to dispel the softspoken Asian American woman stereotype. With the goal of moving to a senior position after 20 years in the wines and spirits industry, she was one of the more vocal members of the Asian ERG at Moët Hennessy. With new leadership in place, there were promises for change, including diversity across all levels of the organization.

“There was some sense of hope that we would be recognized. That was not what happened,” said the 45-year-old marketer, shaking her head. Instead, “It was like a great pat on the back. Great job. Great conference, great zoom, great insights, but then no action,” said Greenidge, twirling the beaded bracelets on her wrists.

Not one Asian American woman was promoted to an executive position out of the 100 employees in the ERG. Although bittersweet, Greenidge decided to leave her company’s employee resource group. “I had to truly ask myself, could I continue to be part of a group that’s not being heard? And it’s just for show?”

Part of the problem is that Asian American women are excluded from the leadership pipeline. “It has to start from the very top. That’s the issue. Leadership doesn’t recognize the importance of pulling up Asian American women. It’s not on their radar,” said Greenidge.

Kristyne De Jesus, 35, hoped to be part of the leadership pipeline at Verizon where she struggled to climb the corporate ladder. The Filipino American marketer turned to Verizon’s ERG, Women of the World (WOW), and participated in 12 months of intense online learning and interactive workshops on mentorship and sponsorship.

While the employee resource group did not get De Jesus promoted, the “WOW was an opportunity to show that I was a leader and could manage more than product launches. I could manage people,” she said.

De Jesus believes that employee networks can embolden employees to apply for a job, request a raise, ask for more support, or speak up when they deserve a promotion. However, she said that companies also “need to look at recruitment and career development processes. We need a little more diversity, especially at the top level of the company.”

For Asian American women in corporate America, De Jesus’ advice is to remember that “An ERG is just one step. Asian American women need to hold companies accountable for change.” Cradling her chihuahua and proudly showing the Filipino sun tattoo on her arm, she said, “We deserve a seat at the table just like anyone else. Kick ass!”

Kristyne De Jesus and Bubba. Credit: Jannelle Andes