One of Tampa’s oldest African-American cemeteries, Zion Cemetery, was almost lost to history when a housing project was built over it. Residents have been forced out as archaeologists excavate the area and relocate an estimated 800 caskets. [ Credit: Tampa Housing Authority]

(TAMPA, FL) — While the city of Tampa celebrates its immigrant roots, it often ignores the history of the racist byproduct of metropolitan areas’ growth. Nowhere is that more prevalent than East Tampa, where redlining in the early 20th century left its mark on the predominantly Black neighborhood.

As with many expanding regions, gentrification crept into the community and gradually attempted to erase its citizens’ culture and history. The repurposing of gravesites and cemeteries without reburial and the lack of proper archives are prime examples of this erasure.

In an ironic turn of events, East Tampa residents now fight to balance the history of their community with the encroaching growth of the metropolitan area. After years of being shut out of nearly every other community, the unforeseen side effect of desegregation is that established communities of color lose landmarks, homes, land, schools, and community centers to developers and new residents.

Finding a Missing Past

Last year, the Tampa Bay Times, the area’s local newspaper, launched an investigation into several missing cemeteries, finding three in the East Tampa neighborhood alone. This added up to thousands of graves of local African-American residents buried over a century ago that were basically just erased from history and instead used as an apartment complex, a high school, and an Italian immigrant cemetery.

In an odd twist, most of these former Black cemeteries were simply erased from existence and repurposed for other Black community options. The apartment complex, now called Robles Park Village, is part of the city’s housing authority, a project built in the late 1950s as a community of cheap housing for the majority of Black residents in the area. Even today, the 70-year-old buildings, sitting in the heart of the roughest part of the city, are crumbling, with rotting foundations, chipping paint, and boarded up windows.

In June 2019, Times reporter Paul Guzzo discovered that Zion Cemetery appeared on area maps from 1901-1925. At that point, it became a large vacant space on successive documents until Robles Park was built about 30 years later. An archaeological researcher at the University of South Florida, Rebecca O’Sullivan, then contacted the Tampa Housing Authority (THA), which runs Robles Park. They quickly discovered that five buildings in the complex were built on top of about 130 buried caskets in the former cemetery, though there are over 800 death certificates on file that list Zion Cemetery as their final resting place.

Robles Park Village was already scheduled for a refurbishment, as Leroy Moore, THA’s Chief Operating Officer, said. This new development simply sped up the plans and focused the priority on these buildings first. Currently, there is a large fence around the buildings with colorful banners to explain the history of the missing cemetery, including a list of names of those known to be buried at Zion Cemetery over a century ago. THA arranged and paid for relocating residents living there when the discovery was made to help convert the property into an archeological dig.

Zion is not the only cemetery nearly erased from history. The Times found at least nine lost cemeteries in three of the counties that make up the Tampa Bay area. Local politicians, like State Senator Janet Cruz, are leading the charge to establish a state-sponsored formal memorial site for those previously lost to history.

Gentrification: Community Evolution or Crushing Culture?

Despite this unexpected consequence, gentrification has its upsides. Tampa’s housing market is skyrocketing, causing many middle-class residents to seek housing options in previously undesirable neighborhoods. Years ago, real estate gurus discovered the appeal of more affordable housing, acquiring land in lower-income areas and converting them to newer, relatively inexpensive, homes and apartments. The conversion often brings a stronger economic base to the area, and there is a push to update the surrounding community to support these newer residents.

Just a five-minute drive down the road from Robles Park Village is a brand new four-story apartment complex featuring city-style lofts. Despite the pandemic still raging through the area, local restaurants are popping up and becoming neighborhood hotspots. The two main roads that bisect the area used to be filled with sagging, aged strip centers boasting pawn shops and small businesses. Many are now renovated buildings focusing on upscale or chain restaurants, medical offices, and niche businesses.

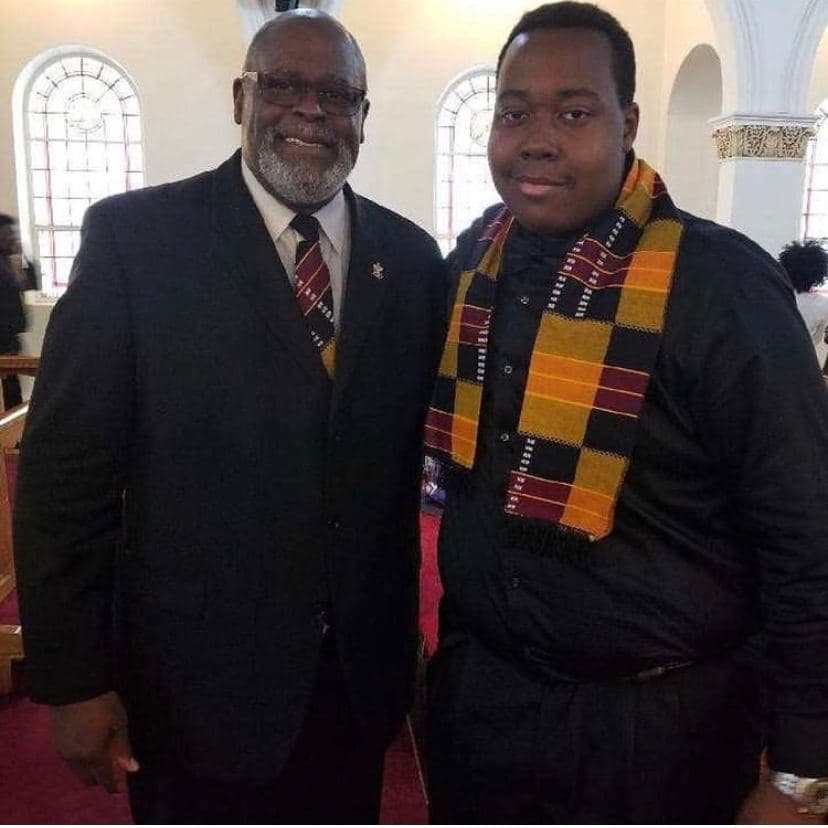

Residents still maintain a cautiousness over certain parts of the area, seen still as the “bad part of town,” and the area of higher crime rates, according to local statistics. Joshua McDonald, a college student from East Tampa, is currently enrolled at Morehouse College in Atlanta but stuck in Tampa to do online courses due to COVID-19 restrictions. Joshua said that he’s been warned his entire life about not crossing certain borders into those “bad areas” due to their history of violence, drugs, and gangs. He and his father Charles, a lifelong resident of East Tampa, agree that the areas are much smaller than they were in the past, especially in the elder McDonald’s time.

Joshua says these days “it’s centralized around the [former] dog track, which has always been bad and just got worse when they shut down the racing.” Joshua suggested that gentrification is actually the main reason that these former bad neighborhoods are becoming less of a problem in the area. “A few years ago, in the West Tampa area, they just finished tearing down the projects, and they’re just now starting to build up new apartment complexes, and most of the families in that area moved. It used to be if you were from West Tampa, you got caught on this side, it would turn violent.”

“Generally, gentrification means essentially the white people moving into the Black neighborhoods. Positive things include that it’ll build up property values, and it’ll ultimately make the area look a lot nicer,” said Joshua. He also explained the negatives include pricing out long-time community businesses or residents who lived there for generations. “Because the projects are affordable housing. And where are you going to send them? What if they can’t come back because they can’t afford it now?”

When asked about the issue with the lost cemeteries, Joshua said, “Essentially, one of the other issues we had with the cemetery is that essentially you’re erasing history. People cannot go and visit Great Uncle Bob’s grave. They don’t even know where it is or that it’s under an apartment complex now.”

But communities need schools, community centers, churches, and places that are community-oriented. It’s part of the natural evolution of a community. The question remains then if it’s all worth it. Isn’t it just a natural part of the development of community?

“The difference between gentrification and regular community development is the people,” said Joshua. “What makes it gentrification is when people develop the community but price out the residents from moving them out and not making it feasible to come back.”

Generations of History

Charles McDonald and son Joshua are long-term residents of East Tampa, eyewitnesses to many of the neighborhood changes over the years. Photo courtesy of Joshua McDonald.

Joshua’s father East Tampa native Charles McDonald, 67, has been an eyewitness to many of the changes to his community. Originally, due to segregation, McDonald attended the only Black high school open at the time, Blake High School in West Tampa. McDonald should have attended his local high school, George S. Middleton High School, the first Black high school in Tampa. But a second arson attack burned the school down in 1968 and thus affected McDonald’s education, forcing him to attend schools outside his community. When desegregation orders took effect, he was bussed to a former white high school in South Tampa, Plant High School. However, McDonald said that most of the football team at Plant were fellow Black students from his own neighborhood.

McDonald recalled his high school with mixed feelings. “Coming from a school in the ‘hood and going to a school that was where the rich kids went,” he said. “And the football team and players had everything they wanted now. They’re getting what they didn’t have — speed and beginning aggression.” McDonald related how the diversification of those athletes made a more well-rounded championship team.

But despite some problems in school, McDonald found that in athletics “there is no color, only your ability to perform and do your job. They don’t give a damn what color you are if you can make that block, you can get a good score, you can win it. That’s how you’re judged. And how we got along in the end. They used us as ambassadors for the school to show us working together.”

Instead of rebuilding Middleton again at the time, the district opted to transfer the name to an area junior high school. But when area growth demanded a new high school, city officials acquired land from a local trailer park through eminent domain coincidentally as part of a gentrification project. Since the new school was built within the same East Tampa community, activists pushed for a renewal of the Middleton name and legacy. Thus, George S. Middleton High School re-opened in 2002. McDonald was asked to join the football coaching staff in 2003, and years later would coach his youngest son Joshua, who wore the neighborhood team jersey Charles never got to wear.

“So many times, they’ve just torn down these houses and buildings that have such a rich history,” said Joshua. “They promise to renovate or rebuild, but it’s just an empty lot. They’ve tried to get rid of the poor, to move out the undesirables, and just forget them. But those cemeteries are a collection of stories and histories of the community. And you can’t erase it. You can’t erase a community.”