MONTREAL — On Jan. 17, 2021, Raphaël “Napa” André was found dead inside a portable toilet in Montreal a few meters from a homeless shelter called The Open Door. It had been closed overnight due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

In May, more than four years after André’s death, Québec Coroner Stéphanie Gamache released a 75-page report (in French) on the cause of his death. According to her report, he died of hypothermia after being denied entry to several homeless shelters in the days leading up to his passing.

“It was a difficult investigation because the circumstances of the death were, in my opinion, truly inhumane,” Gamache said during a press conference the day she released the report.

Less than a week after André died, the Clinique Juridique Itinérante (Mobile Legal Clinic), sued the government of Québec on behalf of “S.A.,”a homeless man, who wished to remain anonymous. The suit sought to ban the application of Section 29 of Decree 2-2021 ( the 8 p.m. to 5 a.m. Montréal curfew put in place during the COVID-19 pandemic) for homeless people, who were adversely affected by it, according to the suit.

The curfew had prevented André from accessing warmth and a roof over his head on the night he died. For Jean-Marc Bonhomme —who almost lost a toe when experiencing a winter in Montréal as a homeless person — being exempt from the curfew was a win, but it wasn’t enough in the context of the pandemic. “You got Place Dupuis [temporary shelter], and now there’s two other shelters, but that’s not enough,” he told CBC News.

For Sam Watts, CEO of the Welcome Hall Mission, these temporary solutions, while necessary, still fall short. He says the city needs to develop more durable, systemic approaches.

The plaintiffs argued that applying the curfew to homeless individuals was unconstitutional and violated their right to life under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, as it effectively criminalized people without a home to return to during curfew hours.

On Jan. 26, 2021, only nine days after André’s death, the Superior Court of Québec granted an interim stay, exempting homeless people from the curfew. Soon after, the Québec government amended Decree 2-2021, making the exemption permanent.

André’s death is a tragic chapter in a broader story, that of homeless Indigenous people, mostly from Innu and Inuit communities, living on the streets of Montreal. According to an April 2024 report (French) by the Montreal Indigenous Community Network, Indigenous individuals make up only .6% of the city’s population but represent 12% of its visible homeless population. André, Innu on his father’s side and Naskapi on his mother’s, traveled from Matimekush-Lac John in Québec’s Cote-Nord region to Montreal after “falling in love with the city.” said father Daniel André, to reporters Lindsay Richardson and Shushan Bacon in an article for ATPN National news.

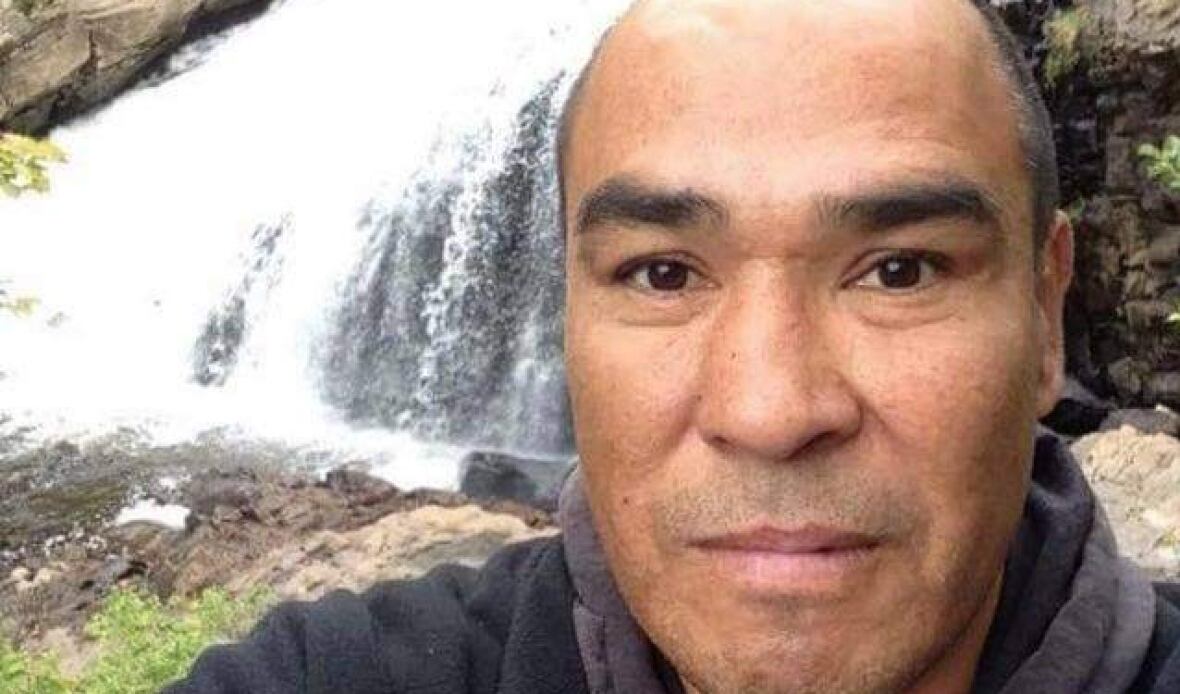

Raphaël “Napa” André [Credit: CBC News]

Like many Indigenous people experiencing homelessness in Montreal, André lacked access to culturally appropriate housing, or any housing at all, while facing frigid winter temperatures.

“Cultural safety must be at the core of all services provided to First Nations, particularly for people experiencing homelessness and those facing its impact,” said Derek Montour, President of The First Nations of Québec and Labrador Health and Social Services Commission in a press release from the Assembly of First Nations Québec-Labrador.

André’s death exposed the consequences of disregarding the city’s homeless population when implementing public policies like the COVID-19 curfew.

A year after his death, a memorial tent funded by the community and government was set up in Montreal’s Square Cabot, welcoming 72,888 people by Jan. 16, 2022, and operating until March 31 of that year as a temporary shelter with 17 mats for overnight stays and food for many more.

The report by Gamache, the coroner, issued following a 20-day public inquest, concluded that André’s death by hypothermia was avoidable and lists 23 recommendations to prevent such deaths: “We must keep in mind our collective responsibility when a death occurs that was avoidable,” wrote the coroner.

The recommendations for Montreal and Québec are organized into five sections: 1) increased monitoring for homeless individuals, 2) culturally safe Indigenous accommodations, 3) emergency health plans, 4) permanent funding for emergency housing, and 5) training for community organization stakeholders.

The problems the report seeks to address are compounded by a sharp increase in homelessness across Québec in recent years. Between 2018 and 2022, the number of people experiencing homelessness increased by 44% across the province. according to the Movement to End Homelessness in Montreal non-profit organization.

In 2022, the agency counted 10,000 homeless people, with nearly half located in Montreal, a 33% increase for the city since the last count in 2018.

Mobilization for increased services for the homeless community is a recurring topic in Montreal news. One case involves the Notre-Dame Street encampment, where about 30 people are currently living. The question of whether they will be evicted is now before the Superior Court of Montreal, which will hear the case between the Clinique Juridique Itinérante and Québec’s Transport Ministry, the owner of the land, between Sept. 29 and Oct. 1.

Meanwhile, the city’s subway system has introduced a new policy banning loitering until April 2026. With the subway no longer serving as a safe public space for those looking for warmth, shelters are expressing concern about the growing gap between the number of unhoused people and the limited availability of shelter beds. Especially with winter approaching.