(DENVER) — The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently stated that it would be happy to share hundreds of thousands of pages of COVID-related documents — but only at a pace of 500 pages per month over 55 years. On August 27, 2021, four days after the U.S. government approved the Pfizer COVID vaccine for individuals aged 16 and older, the non-profit Public Health and Medical Professionals for Transparency (PHMPT) filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, seeking “all data and information related to the Pfizer vaccine.”

In September 2021, PHMPT filed a lawsuit for the public records. The FDA responded two months later, saying that it would release the most crucial documents by January 2022 and would then slowly release the remaining pages over the next 55 years.

It has been 55 years since Congress enacted the Freedom of Information Act. While FOIA stipulates that people have rights to public records from government agencies so that the public can understand “the inner workings of the government”, in recent years, FOIA has gained a notorious reputation for extended delays or even non-responsiveness. Shelter-in-place orders and remote working arrangements during the pandemic further highlighted FOIA frustrations as some agencies completely shut down FOIA requests. To get agencies to comply, requesters sometimes have had to file lawsuits.

In an article in September 2020, lead lawyer of the New York Times, David McCraw, explained the FOIA process and its problems.

“A citizen puts in a request, and a FOIA officer decides whether any documents can be released,” he wrote. “If the request is denied, a second FOIA officer hears an appeal. Because the law around FOIA has grown so complex, the officers are often forced not just to apply the law but also to interpret it.”

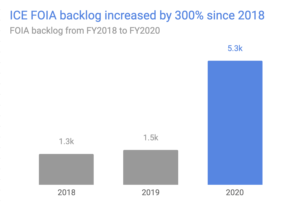

Over the past several years, the volume of FOIA requests has been increasing. Based on data from FOIA.gov, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) under the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) had an almost 300% increase in its backlog from fiscal 2018 to fiscal 2020.

[Credit: FOIA.gov]

The rest of the requests are either first-person requests, where requesters are requesting records about themselves, or commercial requests, where records are part of a for-profit enterprise such as consulting or information resellers. In an interview with Kwoka for her book, a senior FOIA official from the DHS told her that he believed that there was “a direct connection between the large number of routine, non-oversight FOIA requests and the difficulties that news media face in effectively using the law.”

The FOIA law requires agencies to release the requested records within 20 business days. Data for the CIA showed that in fiscal year 2020, the average number of days required to process a simple case was 6.9 days and for a complex case, 331 days. The average number of days for expedited processing was 41.6 days.

NYU Professor Charles Seife explained in an interview with The Click that FOIA performance of agencies is currently being tracked based on the number of simple and complex requests that were processed. Instead of separating between simple and complex, he suggests that agencies should be measuring based on their responsiveness to public interest FOIA requests versus personal or commercial information requests.

Measuring performance based on the current simple and complex requests indirectly incentivizes the processing of simple requests that can be processed quickly to improve the overall performance for the agency while disincentivizing more complex requests that may have been stuck in the backlog for a long time and that may take more time or resources to complete.

In an interview with The Click, an official in a large government agency explained the problem with the current measurement.

“Because requests don’t actually get processed first-in-first-out, those very big, complicated requests tend to sit in an agency’s backlog for a very long time,” she said. “If you don’t process it, you don’t account for it in the annual report. So the older the request, the less incentive there is to end the request, because it is going to make the average processing time longer.”

One way to force the agencies to release FOIA documents more quickly is to file a lawsuit. Investigative journalist Jason Leopold explained the power of suing for FOIA documents.

“The law gives me the opportunity to seek relief in court,” Leopold said. “If the agency does not respond in the timeframe that’s required by the statute, or if they claim ‘We didn’t find any documents.’ and I believe that there are some, I’d appeal and go to court.”

“When I go to court, that opens up a new door. The court requires a response in a certain amount of time, and I get to the top of the pile, so to speak,” he said.

Lawsuits have become an important part of the FOIA process. A report from FOIAproject.org showed that there has been a significant increase in lawsuits over the past 20 years. In 2020, there was a 22% increase in FOIA lawsuits over 2019. The report also noted that over the four years during the Trump administration, 386 lawsuits were filed, which is more than the 311 lawsuits filed during the sixteen years of the Bush and Obama administrations combined.

Large newsrooms such as New York Times (NYT) hire full-time in-house lawyers to handle FOIA lawsuits. NYT’s McCraw, noted in his article that their legal team spends hundreds of hours filing lawsuits each year and while the lawsuits drag on for a long time, he found motivation in regularly “making a dent in government secrecy”.

Unfortunately, with newsrooms facing reduced funding and journalists moving to freelancing, not all journalists can afford to sue for public records. Seife said that once he had his first lawsuit, he recognized that filing suit would become an important component of successfully pursuing FOIA requests. Even though it was a lot of work, his expenses were reimbursed because of the part of the law that says that when the requester wins a FOIA lawsuit, the agency must pay the legal fees. “It ended up being around a thousand dollars, but it is still a lot to a freelancer. But it is not insurmountable, especially since I expect to get my money back,” he said.

“Newsrooms automatically believe that filing a lawsuit would be an exorbitant cost, when it is simply not the case. There is a cost associated with it, but it is not for one case hundreds and thousands of dollars. Attorneys would collect the attorney’s fees [from the government agency when the case is won],” Leopold said . “Most newsrooms just don’t think of FOIA as an investment. They believe that it is too expensive. Newsrooms think that the money is better used for something else.”

Another way to get help with filing FOIA is through non-profit news sites, such as MuckRock, which was founded in 2010. For a minimum fee, Muckrock provides “advice, postage, and follow-up” to FOIA requests filed through the news site and facilitates sharing documents.

Leopold and Seife, both long-time FOIA requesters, have observed changes with the public records obtained through FOIA over the years. Some agencies appear to be stretching the response time on difficult and sensitive requests beyond what is actually required in the hope that the news cycle will move on and no one will care about the news anymore.

“I waited a long time [before] for the information but not this long, and the information that I get from various agencies is not as redacted as it is now. It was still difficult [before], but it wasn’t that difficult. Now I find it a real battle to get anything out of the agencies.” said Leopold. He recently received three pages of information from the CIA. It was from a FOIA request he made seven years ago. He thinks that some agencies hide behind the backlog as they do not want to give out the information.

Seife also noticed differences from when he started using FOIA over ten years ago. He found that even the smaller agencies have become warier of FOIA. While all laws fail in some sense, Seife thinks that the point of suing is to ask the court to bend the interpretation of the law in support of FOIA requests. With FOIA, Seife is sensing that the courts are becoming less willing to broaden the interpretation of the law. “The opportunity to make good case laws is diminishing and after a certain point, Congress has to step in and rewrite the law to make it clear,” he said.

In an interview with The Click, Kwoka stressed that there are ways to structurally improve the FOIA laws that would ensure that journalists could get quicker and more complete responses.

Kwoka believes that the FOIA process should be more narrowly focused on matters of public interests with alternative paths for the public to access personal or commercially relevant information. With less volume, FOIA offices will be able to process requests in a more timely and comprehensive fashion.

PACER – Pubic Access to Court Electronic Records [Credit: pacer.uscourts.gov]

Another way to strengthen FOIA is to find an alternative to going to court when an agency is violating the law. One particular example in the U.S. is in New York, which has an independent oversight board called the Committee on Open Government to handle the state’s public records appeals.

Kwoka firmly believes that Congress’ underlying intention for FOIA was government oversight and that the agencies should provide resources to expeditiously and completely focus on providing public interest.

FOIA keeps the government transparent and holds decision-makers in the government accountable. It is how citizens understand what goes on behind the scenes in the government. It is how journalists inform the public and maintain the Fourth Estate.

As NYT’s McCraw wrote in his article, FOIA allows us all as citizens to push against government secrecy and the leaders of agencies who may have incentives to withhold information. He continued, “If requesters always shrug and walk away at that point [when the request is denied], it means we are leaving it to federal bureaucrats to decide just how secret our government is going to be.”

“That was never part of the plan for democracy,” McCraw wrote.