November 18, 2025

Categories

Community, Education, Features, Health & Science, Science, Travel, Video

Tags

Share

(LOS ANGELES) — High atop Mount Hollywood, overlooking the city, sits one of Los Angeles’s true “star” attractions — Griffith Observatory. Larger than New York’s Central Park, the 3,000-acre Griffith Park has been welcoming visitors since 1935, offering not just sweeping views but a window to the cosmos.

The idea for a public observatory was born from one man’s moment of wonder. As curator David Seidel explains, Griffith J. Griffith — the park’s namesake and benefactor — “was able to look through a telescope up at Mount Wilson, and he had this epiphany that if everyone could look through a telescope, they would change their perspective on the world and on the universe.”

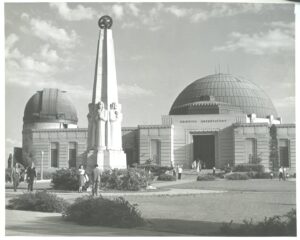

Griffith Observatory in the late 1950s. (Courtesy: Griffith Observatory)

That flash of inspiration was radical for its time. In an era when most observatories were reserved for scientists, Griffith envisioned a place where anyone could look skyward — for free — and feel part of something larger.

Nearly a century later, that vision is thriving. More than 1.6 million people visit Griffith Observatory each year, making it one of the most popular public observatories in the world. From school groups and tourists to lifelong Angelenos, the crowds who climb the hill come not only for the views but for a chance to see — and understand — the universe.

The moment visitors step through the building’s bronze doors, that mission comes to life. Beneath its art deco rotunda, a brass pendulum swings slowly back and forth — the Observatory’s famous Foucault pendulum, which has been marking the Earth’s rotation for nearly 90 years.

“It’s the first thing people see when they walk in,” says Wes Hughes, one of the staff members who manages visitor flow through the building. “When someone can see something that explains something we take for granted — having that proof that our world is turning is a really nice thing.”

“It’s the first thing people see when they walk in,” says Wes Hughes, one of the staff members who manages visitor flow through the building. “When someone can see something that explains something we take for granted — having that proof that our world is turning is a really nice thing.”

The Hugo Ballin Murals (Courtesy: Griffith Observatory)

Above the pendulum, the building itself tells another story. Murals by Hugo Ballin ring the dome, painted in 1934 in a style that “really screams 1930s,” says Seidel.

“One of the attributes of the building is its symmetry,” he says. “It’s a striking and recognizable building.”

Much of the foot traffic, though, heads straight for the Observatory’s legendary Zeiss refracting telescope. More people have looked through it than any other telescope in the world.

“This is the reason why Griffith Observatory is an observatory,” Seidel says, standing beside the 12-inch Zeiss. “This is what Griffith had in mind. Literally millions of people have looked through this telescope.”

“This is the reason why Griffith Observatory is an observatory,” Seidel says, standing beside the 12-inch Zeiss. “This is what Griffith had in mind. Literally millions of people have looked through this telescope.”

Tour guide Louisa Bradley still finds the experience thrilling. “The Zeiss is really exciting,” she says. “When they move the roof to fit it to the telescope, you feel like you’re part of something much bigger than yourself.”

Downstairs, visitors can see how atmospheric particles from space are pinging us at every moment, find out how much they weigh on different planets, and touch meteorites. Seidel points to one of his favorite spots — a glass case holding a hefty chunk of iron and nickel that landed in Arizona from space. “It’s a direct connection between the universe and people here on Earth,” he says. “That’s what makes it special.”

Dir. Krupp refers to the observatory as the “hood ornament” of the city. (Courtesy: Griffith Observatory)

That connection — between the scientific and the human — is at the heart of the Griffith experience. “The learning experience for visitors really should be about transformations of perspective,” Seidel says. “It’s all about seeing where we fit.”

Outside, high school students snap selfies against the building and others point their cameras across the vast park towards the iconic Hollywood sign.

Ninety years on, the observatory remains one of the city’s most recognizable landmarks — “the hood ornament of Los Angeles,” as longtime director Edwin Krupp calls it. From its telescopes to its pendulum to its hands-on exhibits, every inch of the building is designed to remind visitors of their connection to something infinitely larger.