Mad Platter, established in 1984 in Riverside, Calif., announced in October that its pandemic closure would be permanent. It was an offshoot of Rhino Records & Video Paradiso, still in business about 30 miles away. [Credit: Sonya Singh]

(RIVERSIDE, Calif.) — It didn’t take long to spot. On the second day of his freshman year at the University of California, Riverside, Wolfgang Mowrey perused the list of local hangouts provided during new student orientation. As luck would have it, there was an independent record store called Mad Platter in University Village, just a block from campus.

“I remember just being blown away by that kind of place existing so close to me,” said Mowrey, who was always looking for new music as a part of his job with KUCR radio. The record store in his nearby hometown leaned heavily toward punk rock — not his preferred genre — and he loved Mad Platter’s deep, diverse selection within its bright, poster-clad walls. “You see it in films and media, but you never really dream of being able to go there yourself, or at least I hadn’t. To be able to be present there felt so special.”

He didn’t buy a record on his first visit, but that wouldn’t last. UCR held classes at the movie theater in the village, and Mowrey made it a point to pick up an LP at the Platter after most every class (and sometimes instead of class). His first was “Close to the Edge” by Yes, or maybe Minor Threat’s “Out of Step.” But still not a punk fan, he sold that one for beer money.

For years, it was a hangout for him and his friends. It was a place to go with a date and a space to share an abiding love of music with others who know that feeling well, whether a clerk at the counter or the person rummaging in the dollar bin next to him.

But this year was different. After closing temporarily in March, financial pressure finally became too much to bear, and Mad Platter announced on Oct. 7 that its COVID-19 shutdown would become permanent.

Mowrey, now 26, was one of many who grew attached to Mad Platter during its 36-year run. In spite of the store’s closure, the modern story of the American record store is one of resilience. In the 2000s, more than 4,000 stores — including chains — closed in the United States, leaving about 1,600, according to The Almighty Institute for Music Retail. A decade later, things have held: Nearly 1,500 shops remain, according to a cataloguing project by Discogs, a music database and marketplace.

The longevity and multigenerational appeal of establishments like Mad Platter tell a larger story around physical music, where one listening format tends to give way to another — permanently. No one is bringing back the 8-track, but the 2010s ushered in the unlikely resurgence of the vinyl record.

Independent stores face distinct hurdles in a pandemic

Founded in 1984, Riverside’s Mad Platter was an offshoot of Rhino Records & Video Paradiso, established a decade earlier in Claremont, California. The owner, Chuck Oken Jr., began working at Rhino in 1981, a golden time for physical music and the stores that carried it. Business began to slip around 2010, when smartphones and streaming apps started to become ubiquitous. At the same time, the village began to evolve away from a space where a record store fit.

Mad Platter’s parent store, Rhino Records & Video Paradiso, is still up and running in nearby Claremont, Calif. [Credit: Sonya Singh]

Nationally, nearly 100,000 small businesses closed between March and September, according to a Yelp Economic Impact Report, with restaurants and retail hit hardest. The Paycheck Protection Program, designed to help smaller outfits stay afloat, was plagued by issues including a focus on payrolls, which Oken noted. As a result, some small businesses received little to no relief, while Shake Shack and the Los Angeles Lakers did.

“The overall destruction to all of our small businesses like this is incredibly sad. We’re going to have to live with that,” he said. Surrounded by empty dorm complexes after schools sent students home, Mad Platter also lost its young patrons from UCR and around Riverside, a city with several universities and community colleges within easy driving distance from the store.

After stay-at-home orders were lifted, Oken faced another challenge: getting staff to return to work in a time of expanded unemployment benefits and health hazards. For record stores everywhere, virus exposure is a concern — the entire experience revolves around touching merchandise, talking with staff members, and gathering for in-store events.

The lone occupant of Mad Platter, which closed in October after a run of 36 years, still sports a store T-shirt. [Credit: Sonya Singh]

“You go to Mad Platter or your local coffee store for knowledge and expertise. Trying to find people who know music is kind of difficult these days. They know their playlists. I hate to say it, but it’s not like [the movie] ‘High Fidelity.’ We don’t sit around getting stoned and mackin’ out,” he said with a laugh. “We work. It takes a lot of work to stock product and music from all over the world.”

Still hopeful, Oken held on as long as he could. He took out a second loan on his house, but in August he knew he had to face the music. He chose to close the Platter and focus on its parent store, Rhino Records & Video Paradiso, which continues to thrive in downtown Claremont, about 30 miles away.

“It was a sanctuary for people,” said Chuck Oken Jr. “The people that come here, this is where you worship music. I was here when David Bowie died five years ago. Some people didn’t know where to go, but they came here.”

Fewer stores, more sales

Perhaps contrary to expectation, closures or consolidations are not necessarily an indicator of disappearing demand for physical music.

“You never want to assume a store closing means the market wasn’t there to support them,” said Carrie Colliton, co-founder of Record Store Day (RSD), an organization that celebrates, supports, and connects independent record stores.

“Stores close because they were in a great spot and the world got around to knowing what a great spot it was, and now that spot costs a lot more money, and they can’t afford the lease. Stores close because the owner was the only employee and got a better offer, and, also, his wife just had a baby. They close for all kinds of reasons. Some do close because they just can’t make ends meet selling what they’re selling. I feel bad for those stores, because that does happen.”

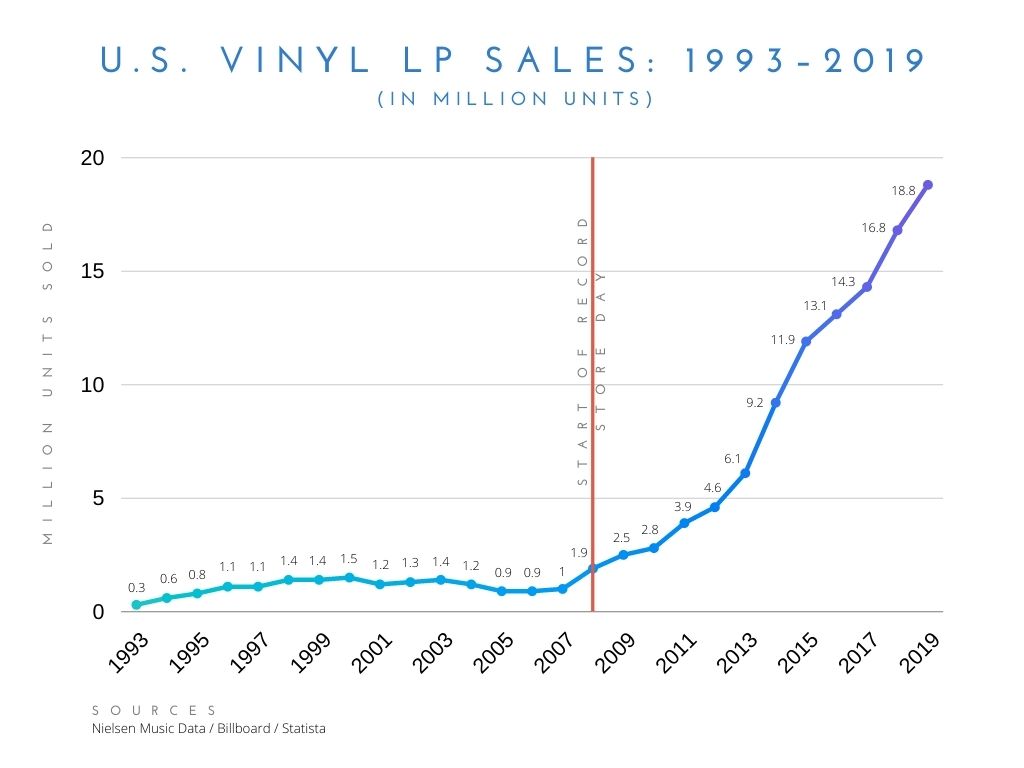

It’s true that overall sales of both physical and digital albums have declined steadily in the 21st century, dropping from more than 500 million units in 2007 to 113 million in 2019. Vinyl sales, though, have enjoyed a rise for 14 consecutive years, surging from roughly 1 million units in 2007 to nearly 19 million in 2019, according to Nielsen Music’s yearly data. Although vinyl occupies a modest space in the market, it is the only album format to enjoy sales growth in the last decade.

[Credit: Sonya Singh]

When talking about vinyl’s comeback, Colliton avoids the word “fad” — fads don’t trend upward for nearly 15 years with no sign of slowing. Both she and Oken described it as a reaction to the digitization of everything.

“[Vinyl] really is a hands-on experience. … From the way it’s manufactured to the way you listen to it, it’s a human experience,” Colliton said. “That sounds really goofy and highfalutin, but it’s not. There’s nothing easy about vinyl.”

Again and again, vinyl fans prize the human experience over the extra care it requires, partly for the discovery and community built into the process.

“I never grew out of music — I still go to concerts, and I’m still discovering music,” said Dana Reed, product manager at Rhino Records. Reed has been with the store for 16 years. Before she worked at Rhino, she used to ditch class in high school to shop there. [Credit: Sonya Singh]

“She was the sweetest person there,” Mowrey said. Having enjoyed “Summer Lawns,” he returned the next day. The same staffer greeted him as he dug through more singer-songwriters, and she and another employee fell into a discussion with him about Harry Nilsson and Randy Newman. “It’s those kinds of moments I’ll miss the most.”

Oken said his standout Platter memories include the heyday of the ’80s and MTV, performances from well-known acts like Korn and local bands like Spiderworks, and moments when people could find more than a record when they walked through the doors.

“It was a sanctuary for people. I’m not a particularly religious person, but I like good things, and I do at times call [Rhino Records] a church,” he said. “The people that come here, this is where you worship music. I was here when David Bowie died five years ago. Some people didn’t know where to go, but they came here.”

Local musician Jake Haber browses Rhino Records on the last installment of Record Store Day 2020. Vinyl sales have enjoyed a significant rise for 14 consecutive years. [Credit: Sonya Singh]

Though she lives in Raleigh, North Carolina, Colliton was sad over the closure of Mad Platter, a shop and a staff she liked in Riverside, California. She knows this year has been especially jagged, and some stores, like the Platter, would still be open if not for the pandemic.

No strangers to surviving a changing market, record stores have fought back by ramping up their websites, embracing social media, and getting creative with appointment shopping, delivery, and more. She braced for more closing announcements this year, but as far as she can see, a tidal wave of shuttered shops never came.

The idea that record stores are dying and that fewer and fewer people care about physical music, she said, is a misguided narrative. When stores like Tower Records closed and Best Buy largely stopped carrying CDs, that was simply one part of the story.

“What they really meant was Tower is closing, FYE is closing — these big corporate stores are closing. But there were great stores in Oklahoma and Nebraska and Portland, Maine, and Portland, Oregon,” Colliton said. “We were just frustrated that the world, pop culture, press, everybody was saying record stores were gone, when our entire world was record stores.”

In response, she and co-founder Michael Kurtz established RSD in 2008 to, essentially, coordinate a massive party that celebrates the culture of the independent, brick-and-mortar record store. During the annual event, participating stores offer meet-and-greets, exclusive music releases, performances, and more — and invite the press to cover it.

Customers consider some branded store merchandise on Record Store Day, an important day of revenue for independent stores since its launch in 2008. [Credit: Sonya Singh]

Artists from Metallica to Brandi Carlile, this year’s official RSD ambassador, have rallied behind the organization’s mission, fueling success that has exceeded Colliton’s expectations. Now, more than 1,200 U.S. stores participate in RSD — they added another 30 before Black Friday this year — and there are participating shops on every continent except Antarctica.

Perhaps not coincidentally, the exponential jump in vinyl sales began around 2008, the year of the first RSD.

“This is going to sound very cliché, but something that’s always stuck out to me is a line from one of my favorite movies, ‘Almost Famous,’ that says, ‘Whenever you’re sad, go to the record store and visit all your friends.’ And that’s what I would do. … It’d be an escape,” said Collin Hollihan, a patron of both Mad Platter and Rhino Records.

Time to move on

These days, Oken can focus solely on Rhino Records, but the loss of Mad Platter was deeply felt.

After the store posted its closure announcement on Instagram, he scrolled through the expressions of sadness and gratitude left in the comments. There are 154.

“I didn’t really realize how much people cared, to be honest. It hit me pretty hard,” he said. “That people really did care so much — you don’t really realize that in the moment sometimes. We’re so occupied with so many other things. That was very nice. But it was a very, very good run. And that’s how you have to look at it. It’s like your life: We’re all not going to live forever, you know? Do good things. Do good things for others that live as memories.”