NASHVILLE, Tenn,– Renee Dowell, 55, has spent much of her life navigating Nashville’s unreliable transit system. One night, after finishing her shift as kitchen staffer at Vanderbilt University Medical Hospital, she missed the last downtown bus and was forced to walk miles in the dark home to North Nashville in the dark. She called her mother who stayed on the phone with her the entire way to ensure her safety.

“Just think, if you’re getting off work and you’re trying to get downtown for a transfer stop—you missed the bus,” Dowell said. “You have to walk.”

Now living near Dickerson Road, where a bus stop is conveniently located outside her apartment and near her new daycare job, Dowell understands how much a reliable transit system can change lives. She voted for Nashville’s $3.1 billion transit referendum, hopeful it will bring similar accessibility to areas like Antioch, with a few nighttime bus stops near relatives’ homes. Most importantly, she looks forward to 24-hour bus service, so no one else must endure the uncertainty and danger she once faced.

The referendum marks a major shift for Nashville, a city grappling with explosive growth and the infamous title of having the worst commute in the nation, according to Forbes. The plan, which promises expanded bus service, safer sidewalks, and improved transit lanes, is intended to overhaul the city’s transit infrastructure. “For the next generation, we will all enjoy the things we deserve—sidewalks, signals, service, and safety,” said Mayor Freddie O’Connell.

This sweeping plan is the culmination of more than a decade of groundwork, says Michael Briggs, Director of Transportation and Planning for the mayor’s office, “The whole program itself is based on about 10 to 15 years of planning,” he said, noting that the NashvilleNext plan integrates transportation goals with land-use strategies. Since then, over 70 additional plans, from corridor assessments to community updates, have helped shape the framework.

The program was refined with public feedback through the “Choose How You Move” initiative, which included advisory committees and transparent community meetings. A new oversight committee with both technical experts and community members, will track project progress, monitor spending, and ensure transparency.

“Our street infrastructure has barely changed since the 1970s, even as development has surged,” Briggs said. He noted that modernizing sidewalks, signals, and traffic systems is essential for accessibility, safety and functionality in a rapidly growing city.

Briggs emphasized that early successes, like improved travel times and enhanced safety measures, will build trust and lay the groundwork for future expansions.

Alongside transit reform, the Nashville Civic Design Center is working to improve public spaces and preserve community identity amidst the city’s changes. Nia Smith, community design coordinator at the center, solicits input from various communities. “A lot of my role is running around the city and just meeting people where they are,” Smith said. She adds that her role connects residents with decision-makers, equipping them with the tools to advocate for their neighborhoods effectively.

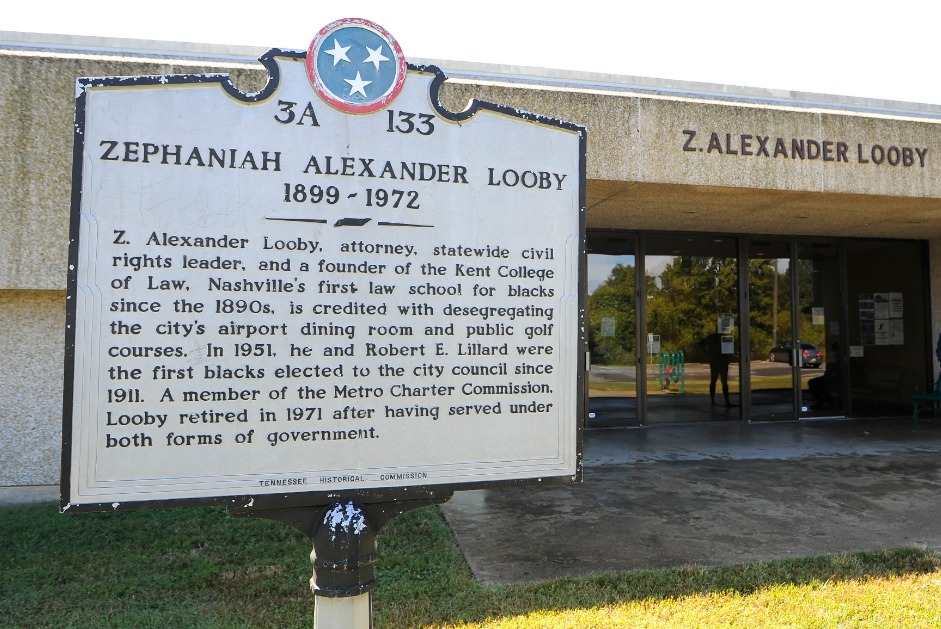

One significant project underway is revitalizing Looby Community Center in North Nashville’s Buena Vista area. Named after Civil Rights leader Zephaniah Alexander Looby, the center has served the community since the 1970s. By enhancing this space, Smith’s team aims to provide resources for nearby schools and families while preserving the area’s cultural significance. This includes plans of extending the access to the Cumberland Greenway, creating outdoor spaces for teens like a designated skate and bike park, a museum dedicated to Looby, upgrades to scoreboards and the basketball court and a community garden. Good

The Tennessee historical marker for civil rights leader Zephaniah Alexander Looby outside of Looby Community Center, which is named in his honor. [Credit: Looby Community Center Facebook]

Still, Smith notes a cautious optimism among locals about the future. “People are excited about a 24-hour bus system. They’re excited about better connectivity, being able to get from point A to point B,” she said.

Smith pointed to Austin, Texas, as a model for balancing development and transportation, noting the similarities between Nashville’s transit referendum and Austin’s 2020 plan, which funded significant transit and infrastructure improvements, including sidewalks, trails, and high-capacity transit systems.

Journalist John Surico, who focuses on urban planning, highlighted how cities like Nashville, Austin, and San Francisco are adapting to post-pandemic demands for walkable, livable communities. While Nashville has gained recognition for its strong tourism recovery and increased downtown residents, according to Downtowns Rebound: The Data Driven Path to Recovery, concerns linger that the city’s focus on downtown development risks neglecting certain neighborhoods.

In East Nashville, the rise of high-rises downtown contrasts with the struggles of longtime residents facing displacement, from families receiving eviction notices to trailer park communities and apartment complexes being demolished to make way for development. These stories underline the fragile trust many feel toward city planning.

“Public transit exists in this weird situation where they have to deal with a really skeptical public,” Surico said. He added that when things go wrong, the public will notice and may blame the mishap on wasting taxpayer money, which can affect support for future projects.

He emphasized that transit systems must focus on transparency and meaningful improvements, like fair fare programs for low-income riders. “You have to show what you’re doing—different thresholds and benchmarks, user experience improvements like ease of payment. Some of the most innovative cities are doing a lot of that right now,” said Surico.

Nashville’s urban development and planning has been under critique throughout the decades for both being hopeful and terrifying to residents, but the locals still place their faith in Nashville seemingly headed in the right direction.

This sentiment rings true for Nashvillians like Renee Dowell; it’s as simple as the city sticking to promises that they’ve made. She’ll trust it, and so will others, as long as the city follows through.

“The world never stops and people keep on going and they need a way of commuting,” Dowell said, “Why shouldn’t I be able to rely on the MTA in my own city?”