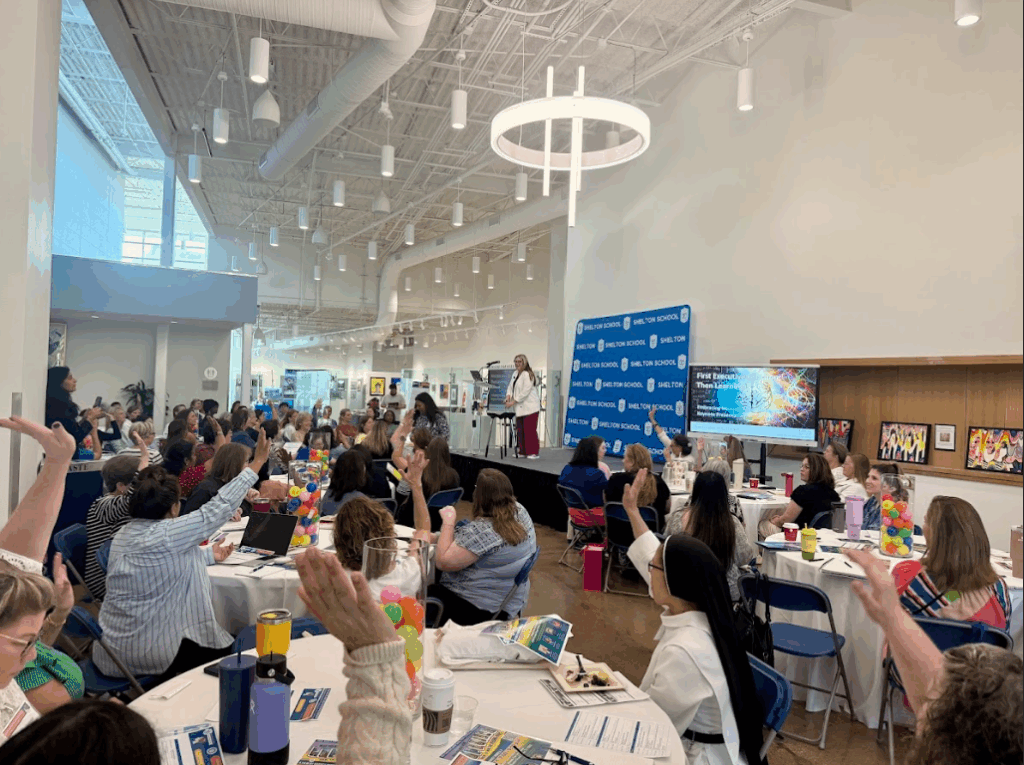

DALLAS, Texas — Educators from across Texas gathered for a bespoke conference with expert panelists on how to best serve learners, particularly those with neurodivergence, by accepting and supporting each individual’s needs. The inaugural event was hosted in September by the June Shelton School and Evaluation Center, a Dallas private school which specializes in education for students with learning disabilities.

Neurodiversity, a term coined 30 years ago, has more recently entered mainstream conversations amidst growing media attention and discourse in science, mental health, and politics. This has driven increased recognition but also some misunderstanding, as keynote speaker Tera Sumpter pointed out to the crowd of over 50 teachers.

In the United States, estimates suggest that one in five children is neurodivergent, meaning they exhibit learning and thinking differences in how the brain receives, processes, and responds to information. Neurodevelopmental conditions include, but are not limited to, dyslexia, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and autism. Still, nearly one in five school districts in Texas are consistently noncompliant with Disabilities and Education Act (IDEA) federal mandates.

While a long runway toward equality in Texas school settings remains, the “Embracing Neurodiversity” event on Sept. 20 provided attendees with actionable best practices to help students reach their highest potential.

Sumpter, a speech-language pathologist, encouraged the conference participants to focus on working with students by addressing their executive function — the boss of the brain.

“The biggest misconception is [that] the crux of executive function are the higher-level skills like organization, prioritization, planning. A lot of [educators] don’t have a full picture of how the root system is involved in all of those higher-level skills,” said Sumpter, founder of SEEDS of Learning, LLC®.

By assisting students in developing habits tailored to their own needs and encouraging them to reflect through questions, they become better equipped to acquire higher-level skills on their own.

Students that have not had their root skills and needs met may be unfairly labeled, reinforcing a false stereotype that neurodivergence is linked to lack of interest or intelligence, said Amanda Nikolopoulos, a speech-language pathologist.

This phenomenon can be discouraging over time and lead to educational trauma, she added.

To be effective with Sumpter’s methods, Nikolopoulos suggests it is imperative to understand the student’s background and make sure they feel comfortable in their learning environments.

By “meeting the child where they are,” she said. “Guiding them with questions and responding in a positive way. [You] are increasing their awareness and giving them opportunities to self-direct.”