An arch celebrating one of the levels of the civil servant exams along Qing Guo Alley’s main lane. [credit: Theresa Boersma]

(CHANGZHOU, China) – High heels clomp against Qing dynasty stone blocks. Women, thrusting selfie sticks out before their painted and powdered faces, scramble past whitewashed buildings, crowned with dark ceramic roofs that curl up into tight-lipped smiles. After seven years of rumors and renovations, those buildings are finally ready for their closeups, and the women are more than happy to oblige.

A sculpted display dedicated to journalists in a museum dedicated to heroes in Qing Guo Alley. [credit: Theresa Boersma]

More a neighborhood than its name would suggest, Qing Guo Alley is dear to Changzhou’s locals as the home of beloved and sometimes feared historical figures. Its roster of famed personalities includes revolutionaries, linguists, painters, and one of the Communist party’s earliest feminists. This pedigree has protected Qing Guo Alley from the wrecking ball through decades of Chinese Communist Party modernization projects, leaving it as one of the last parts of the city to retain the iconic courtyard houses that once flourished in southern Jiangsu province.

But that fame did not protect Qing Guo Alley from the ravages of time. By 2012, the “pride of Changzhou” was crumbling from lack of maintenance and packed with families sandwiched into houses partitioned to maximize occupancy. That’s when city officials partnered up with a Chinese state-owned enterprise to transform the 17,000 square foot collection of historic homes into a budding tourist destination.

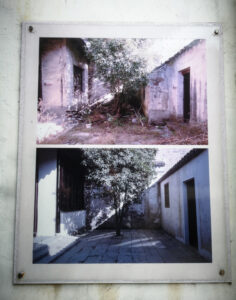

A courtyard in Zhou You Guang’s historic residence before and after renovations. [credit: Zhou You Guang Historic Residence]

Finally, in April 2019, the construction walls around the area came down, and Qing Guo Alley welcomed its first crowds of visitors. The excitement lasted months. Then COVID-19 swept through China and around the world.

“The most difficult part was when we had to tell the businesses to close,” said Bian Wei, management director of Jing Ling Investment Group’s Qing Guo Alley operations. “Spring Festival is an important time for restaurants, teahouses, and so on. People come together to celebrate with their families, they buy presents. But we had to tell them they needed to close. It was not easy.”

With the taming of the coronavirus in China, the newly refurbished photogenic hub of retro boutiques and high-end teahouses is bouncing back. But as life returns to normal, so do the dramas of commerce.

The Guestless Hotel

Peggy Pan, who prefers to go by her English name, has a problem. Song Jian Tang, the boutique hotel she founded with business partner Zhu Yuanjie, has been unable to open for over a year.

“Because of the provincial protection, it is very difficult to do something like this,” she said. “Only one hotel in the entire province, the Changle Inn in Yangzhou has ever managed to open in a historic building with this level of special protection. There are many licenses. Many things to do.”

Entrance to one of the older buildings within Song Jian Tang. [credit: Theresa Boersma]

While charming and part of the allure for tourists, these nearby buildings limit what Pan can do with a hotel in the historic neighborhood. Changzhou has extremely strict fire code regulations that govern things like building materials and the number of exits a hotel must-have. Add to this Song Jian Tang’s status as a provincially protected piece of history, which dictates the kinds of modifications that can be made and the quality of the interior design firm you can use.

“It has been difficult, but I would not do it differently,” Peggy says. “First, this is Qing Guo Alley. Changzhou people have a special feeling about Qing Guo Alley. Especially our parents. Most of them have a special connection to Qing Guo Alley. The second reason is this is the only old alley in downtown.”

The Displaced Chief

Despite no longer living in Qing Guo Alley, Pan Zaisheng—no relation to Peggy Pan—remains one of its biggest fans. His tiny, cramped apartment is packed with remnants of the boisterous life he led there: calligraphy and paintings by famous people he met clutter the walls. He owns a large collection of rocks that he claims are from an emperor’s tomb, and he enjoys telling visitors about how he got his unofficial title, the “Chief of Qing Guo Alley.”

“I am the first who protected Qing Guo Alley,” he said, switching from eloquent Mandarin to English.

Qing Guo Alley before renovations. [credit: Zhao Yuan Ren Historic Residence]

But Pan is proudest of his struggles against Qin Guo Alley’s deadliest scourge at the time: traffic.

“There were many old people in Qing Guo Alley, so with the cars, it was dangerous,” he said.

Pan Zaisheng points out an old inscription on one of the historic houses as he tours Qing Guo Alley [credit: Theresa Boersma]

“I didn’t have a knife,” he said. “So I used the violin.” He waved his hands around as if swinging an instrument.

Pan has quite a reputation. One Changzhou resident, Tao Puyun, who has never met Pan, recognized him immediately by a description. “Oh, he used to get into so many fights when he lived in Qing Guo Alley,” she said.

Probably Pan’s most effective action was a grassroots campaign. He printed large posters about the traffic problem and put them up in areas where they would be visible to neighborhood police. After this, traffic police took a more active interest in controlling traffic in the area until the relocations began.

“It makes me feel uncomfortable—it wasn’t right,” he said of the day officials came to tell him that he would need to move.

The Stubborn Noble

These days, Pan must squeeze past blockades to visit his friends. After Qing Guo Alley’s renovations, the government permanently banned traffic, turning the entire neighborhood into an exclusively pedestrian domain. Even e-bikes, which normally skirt around the edges of traffic laws, are kept out by dedicated security guards.

Zhao Yi Feng stands before the his dining room where he can hold sizable gatherings. His table can seat at least ten. [credit: Theresa Boersma]

“In my family tradition, it is very important to keep the ancestral property,” Zhao said. “It is a shame to sell it.”

The rooms Zhao now occupies are reachable down a dark, narrow alley. The government confiscated sections of his family home in the late 1950s and won’t give those sections back. One is now a store, another part of a museum. The two tiny courtyards and single well left to Zhao are closets compared to what the Zhao family residence once was.

Zhao regularly complained to different government offices over the decades about his confiscated property. “People should be reasonable,” he says. But he doesn’t believe the government has been on this point.

While the confiscation remains a sore spot for Zhao, he adds that he isn’t worried about the government taking away the rest of his house. “I have the house deed,” he said.

In the half-decade since Zhao’s family lost parts of their home, property rights in China have come a long way but remain a thorny issue.

“[Forced relocations in China] are quite different compared with the Western countries because in Europe or maybe in the U.S., they are focusing on the renters in public housing sectors,” said Nanjing Agricultural University Professor Li Xin, an expert on the issue. “[T]hey are like tenants, they are moving from one place to another public housing sector, or they get a certain amount of compensation that can facilitate their movement. But for the Chinese, it’s more about homeowners, so it’s more complicated for the whole process.”

Li explained that in very dilapidated neighborhoods, like Qing Guo Alley before the renovations, often the homeowners no longer live in their homes. “They will rent the apartment out to some migrants or some other people, but the income will remain very limited for this rental phase.” In this scenario, compensation from the government can be a welcome boon to the landlord.

For the Changzhou government and the state-owned enterprise Jinling Investment Group, the relocation period was especially complex.

Bian Wei, the managing director of Jinling Investment Group explained the problem. “Some places had a clear property owner, but in some, the property had been passed down to heirs. Some were still living in Qing Guo Alley, but some had moved to other cities, some weren’t even in China. They moved abroad. We wanted them to cooperate with the government, so we had to talk with them, one by one,” Bian said.

Renters like Pan, however, have fewer rights than landowners. In the alley chief’s case, due to his low income, he now lives in a heavily subsidized apartment in a far less central area of the city. To save money on transportation, he borrows rides from friends and acquaintances.

A Cup of Tea

Li Ercao prepares to make tea. [credit: Theresa Boersma]

Opening her café was a bittersweet homecoming for Li after years spent traveling and studying abroad.

“It’s a little bit sad because not only the kindergarten, the place where I grew up, my grandma’s home, also have been destroyed or renovated,” said Li.

Li grew up in walking distance to Qing Guo Alley, and after the renovations, she returned with her mother to start up a contemporary teahouse that specializes in Fujian white tea and delicate desserts concocted by a Japanese-trained patisserie chef.

Li’s teahouse is an exotic combination of influences that fits well with Qing Guo Alley’s history. Many of Qing Guo Alley’s historic figures like Linguist Zhao Yuanren and Painter Liu Haisu became famous for bringing Western ideas and arts to China where they mixed them with Eastern influences.

“Qing Guo Alley became a melting pot for Western and Eastern arts and culture,” said Hou Di, the former head of Changzhou Municipal Library. Hou is busy these days helping Jinling Investment Group set up the many museums that dot the neighborhood.

It could be argued that Qing Guo Alley remains an East-West melting pot. Tea mingles with coffee. A takeout store for imported craft beer stands across from a noodle shop that also sells Hong Kong-style waffles wrapped around scoops of ice cream. The souvenir shop at the east end of the main lane sells Wi-Fi speakers imprinted with idyllic images of Qing Guo Alley’s houses beside the canal where boats once moored on their routes between Beijing and Hangzhou to trade with local merchants.

Mrs. Liu holds a printed copy of her QR code for a customer to scan. [credit: Theresa Boersma]

There used to be many buyers, including foreigners who came to Mrs. Liu because she could customize her slippers for their large feet, but these days the slippers outnumber the buyers. Mrs. Liu does not fret the slow business, though. For her, it’s just a hobby.

As homeowners in Qing Guo Alley, Mrs. Liu and her husband had the opportunity to sell their home to Jinling Investment Group, but they decided to stay, and have not regretted the decision. The renovations brought running water and electricity right to their home.

“It’s not about the money; it’s about the memories,” Mrs. Liu says in the Changzhou dialect of Wu Chinese, a language distinct from the Mandarin Chinese that is standard throughout China. “That’s why I stay here. My husband and I have memories here.”

Additional translation by Lu Chen Chen