(WASHINGTON, D.C.) – The U.S. Senate’s Subcommittee on Human Rights and Law held the first public hearing on Oct. 25 regarding the rights of children in the care of Georgia’s Division of Family and Child Services (DFCS).

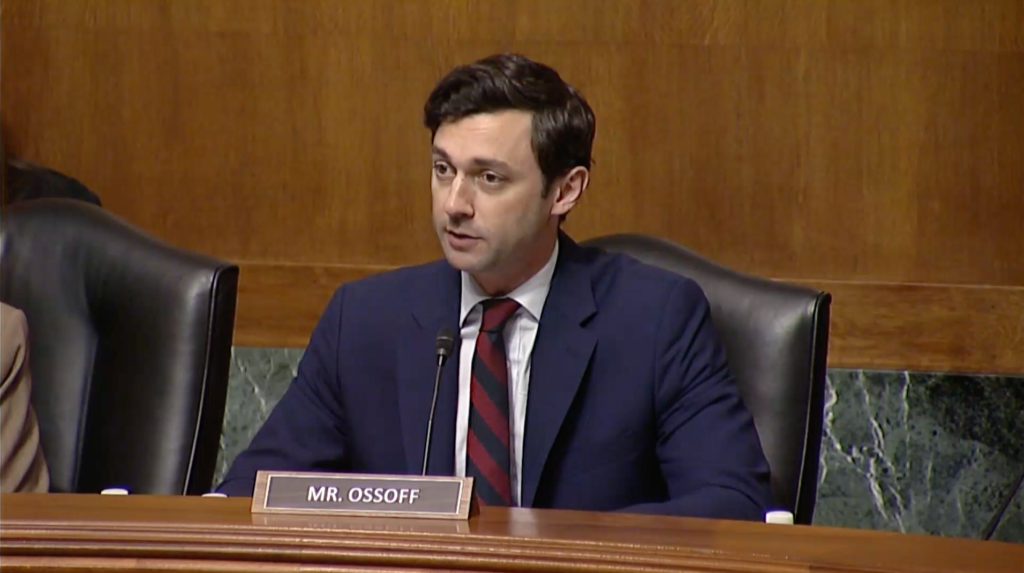

The subcommittee’s Chairman Sen. Jon Ossoff of Georgia and Ranking Member Sen. Marsha Blackburn of Tennessee led the bipartisan inquiry.

WSB-TV reported that the inquiry into the topic began in February because of the amount of reports of alleged neglect of children while in the care or supervision of DFCS. Nearly 30% of these cases were concluded or closed in a single day, state data analyzed by Atlanta News First.

Ossoff and Blackburn opened the inquiry because they “agreed that protecting the nation’s most vulnerable children was a shared priority and moral imperative,” Ossoff said in his opening statement.

“Instead of safety, too many children have experienced neglect, abuse, apathy, humiliation, delayed and denied healthcare, and human trafficking,” Ossoff said.

Rachel Aldridge said her 2-year-old daughter, Brooklynn, was killed while under DCFS supervision. Aldridge said she warned the agency before placing Brooklynn in her father’s care that there are concerns of drug usage and reports of bruising after previous visits to his home.

On Mar. 6, 2018, Brooklynn died and the cause of death was blunt force trauma. The father’s girlfriend was found guilty for the murder in 2019.

Aldridge filed a wrongful death suit in 2021 against the DFCS caseworkers alleging that policies were not conducted correctly. The lawsuit was dismissed the following year, according to online court records.

Ossoff asked Aldridge during the hearing if she believed her daughter would be alive today if Georgia’s DFCS had complied with their own regulations and procedures.

“Yes sir,” Aldridge said in response.

The subcommittee also heard testimony from Mon’a Houston who had been in the foster care system throughout her high-school age years.

“I had 18 placements – only two were foster homes. The rest were group homes, institutions, or hotels. I had three case managers, and only one regularly visited me or answered my phone calls. I would often go more than six months without seeing my case manager,” Houston, 19, said.

While in the care of Georgia’s DFCS, Houston said she experienced isolation, physical restraint, lack of education, and lack of humanity.

“The isolation room was similar to a jail cell, and I was treated as an inmate. You had to request access to the bathroom. I wasn’t allowed to shower. Even when on my menstrual cycle, I couldn’t wash or change for three days,” she told the subcommittee.

After Houston’s testimony, Blackburn asked what qualities would make a good member of the foster care system.

“Nobody’s perfect,” Houston said. “But they didn’t listen. When I acted out, it was the only time they ever answered their phones.”

Nearly 11,000 children are in Georgia’s foster care system and those who enter the system typically have a longer stay than other states, Melissa Carter, a clinical law professor at Emory University, said during the hearing.

Emma Hetherington, the director of the Wilbanks Child Endangerment and Sexual Exploitation Clinic, said only 5% of the children she works with report that they are better now than when they entered the system and 0% report receiving sufficient and consistent healthcare while in DFCS care.

“These clients are children being treated as if they victimized themselves. They are adultified, especially children of color and LGBTQ,” Hetherington said.