BATON ROUGE, La. — “Will these people really want to hear about something a seventy-year-old woman wrote that long ago?”

Jeanette Calametti asks that question the way I expect her to—uncertain, even after all this time. She sifts through a stack of newspaper clippings, their edges slightly yellowed but still perfectly preserved, as if they’d just hit the newsstands in Mobile, Ala.

She leans forward, pulling more articles from the leather portfolio she keeps tucked away. The soft pink nightgown she’s worn for as long as I can remember moves with her, and even now, there’s elegance in the way her silver hair, cut just below her jawline, falls over her face.

The house smells of fresh Community Coffee, the many clocks inching forward in the early morning hours. The sun is barely up, and for the first time in a while, she’s the one being interviewed instead of the one asking the questions.

I drove three hours to talk with my grandmother about her years as an award-winning journalist. Her story began when she felt compelled to tell someone else’s—a man who had just written his first big country hit. It was the late 1980s when she cold-called the Mobile Press-Register, Alabama’s oldest newspaper, and pitched a feature.

“I just got real brave, dialed the newspaper, and was routed to an editor,” she says.

The editor’s response? “I don’t want to know what you have to say about him. Let him tell his story. Give me lots of quotes.”

So, that’s exactly what she did.

She landed the interview, wrote the story, and saw it published. Just like that, she stumbled into a career that would span a decade collecting bylines.

And the editor ate it up. Assigned another piece. And then another. Eventually, Jeanette had her own column. By 1989, if you were in Mobile, you could expect to see her name in print every week.

She sits in her chair, reflecting on that time and what it meant to be a young, newly welcomed female journalist in a male-dominated newsroom.

“I was so new at writing that I didn’t think beyond my own communities,” she admits. “I just met so many fascinating people that I could relate to. The interviews took me to such interesting places and with such interesting people that I was very happy to go from local story to local story.”

The world was shifting. The 1980s and ‘90s marked a turning point in American journalism—investigative reporting was on the rise, cable news was becoming the go-to for national coverage, and newsroom culture was changing. Women were taking up more space in an industry that had long ignored them.

Jeanette, even in a smaller city like Mobile, was part of that shift.

“I was smart enough to know there were some big expert writers handling national and international news,” she says. “I knew I couldn’t compete with them. But I felt keenly that I had a chatty, hometown-gal connection to my stories and the people who shared them with me. That became my style going forward.”

That approach worked. She built relationships with her sources, earning their trust in a way that made her stories feel intimate. Her work didn’t just document Mobile’s history. It preserved voices that might have otherwise been lost.

For eight years straight, she won Outstanding Female News Reporter through the Alabama Women’s Press Association.

“That was back when they kept the women separate,” she says, lowering her voice to a sarcastic whisper.

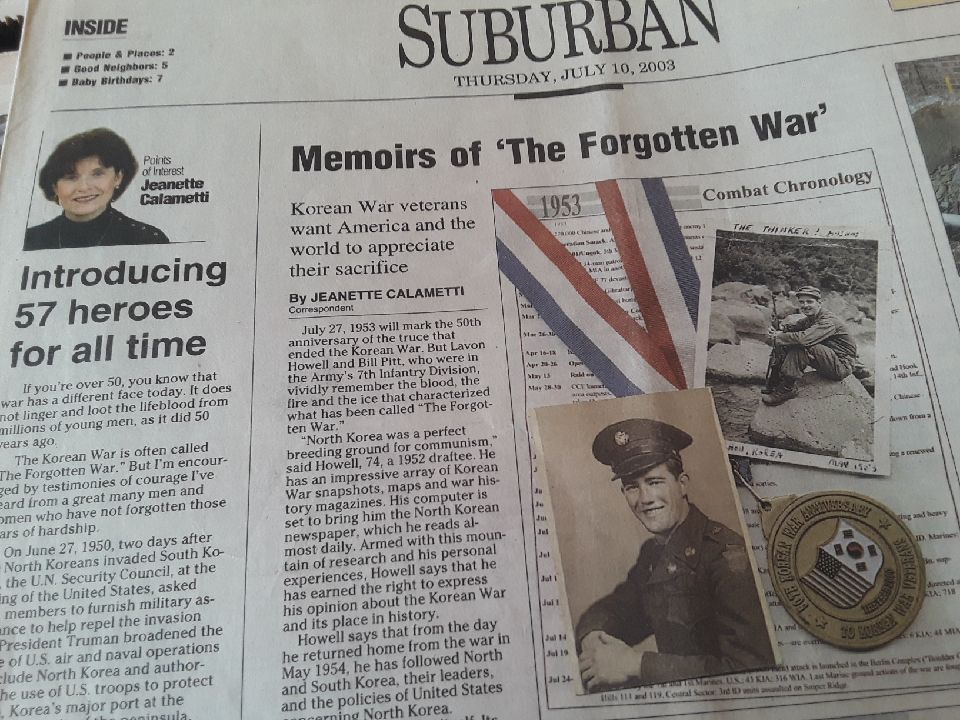

She reaches for another clipping and pulls out a piece titled “Memoirs of ‘The Forgotten War,’” published July 10, 2003.

“I won an Alabama State Press Award for this one,” she says confidently.

She begins reading aloud, her voice smooth and direct, as if she’s transported back to the moment she wrote it: “If you’re over 50, you know that war has a different face today. It does not linger and loot the lifeblood from millions of young men, as it did 50 years ago.”

The story ran just weeks before the 50th anniversary of the Korean War’s truce. She interviewed Lavon Howell and Bill Pitt, both from the Army’s 7th Infantry Division.

Her eyes go glossy as she picks up another clipping. “This was one of my very favorite columns,” she says, holding up “Never Wait to Tell Dad You Love Him.”

“This one brought more emails in than others.” And I know why. My great-grandfather, A.J. “Ed” Bordelon, her father, passed away on December 21, 2002.

“I know you won’t be surprised that I’m going to write about my own father, A.J. (Ed) Bordelon, for Father’s Day,” her story began as I imagined her sitting down writing with her heart feeling heavier than usual. “But what you don’t know is how fresh the pain of my father’s recent and sudden death still feels to me. I can hardly write “father” without an instant flow of tears.”

Eight years after his death, she donated over 300 of his slides to the Museum of Mobile that he captured throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

“We would talk him into getting the slides out and showing us,” she had told the Press Register at the time. “We would sit around the table and hoot and holler. We would watch our lives unfold.”

She looked through her clips with her photography at the top. “I worked with my dad polishing my camera skills,” she remembered. “I even learned to develop and print my own photos.”

Jeanette wasn’t just focused on capturing the people of Mobile. She wanted to capture the city’s essence too– Put her readers into the streets and waterfronts that she knew so well.

She smooths out another piece as she reads the title: “Capt. Red Knows Every Sandbar and Name of Every Bend in River.” She barely made it home before compiling the story of her hours long journey along the Tombigbee Waterway with Captain Red himself.

“When the interview was over, he quite conspicuously pulled the boat right up to the wharf at the foot of Government Street,” she softly laughed. “People were watching and gathered looking at us. He let me off right at the foot of the Government Street Wharf.”

Jeannette stopped writing professionally around 2006, but she doesn’t regret it.

Now she saves her words for her eyes and my grandfather’s ears. If I’m lucky, I’ll get a glimpse or two when I see her.

She looks at me, thoughtful. “You know,” she says, a small smile forming. “You remind me a lot of me.”

I smile back. I think she’s right.