Suki Kim at New America’s Future of War Conference by Eric Gibson

More than 6,000 miles east of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology resides its North Korean equivalent, Pyongyang University for Science and Technology. Similar to MIT, this college is the top program in the country for the brightest scientific and technological minds. The difference? Pyongyang University doesn’t allow access to the internet. The students live in the dark about its existence altogether. The only news provided is through the one newspaper and one TV station run by a regime that solely depicts the accomplishments of their current and former leader.

This is only one example of the type of propaganda and mental manipulation that Suki Kim, an American investigative journalist, reveals in her book “Without You, There Is No Us: My Time with the Sons of North Korea’s Elite.” Kim risked her life by spending six months undercover posing as a teacher at Pyongyang University in hopes of exposing North Korea’s truth from the inside out.

Suki Kim lived in South Korea until she moved to the United States in her teens. Like many Koreans, the Korean War forced members of her family to live in North Korea and growing up with that “separation and sorrow” stayed with her. In 2002, Kim decided to visit North Korea as a journalist and she was both shocked and impassioned with what she found.

“I realized there was this world that was basically a wound, heartbreak for Korean people that is not being explained in a way we can understand,” Kim said. After five trips there, she realized the only way to truly understand the lives of the North Korean people would be to go undercover and immerse herself.

Everything North Korea does is in pursuit of keeping “The Great Leader” at the center of their citizens’ lives to uphold their wealthy regime. They do this by isolating North Koreans from the rest of the world. With a violent military, they enforce a propaganda bubble, concentration camps for labor, and entirely controlled existences. There are over 25 million citizens suffering in an alternate reality with a lack of real information, proper healthcare, and food. “I think my job there was somehow trying to see how is this possible to control people to this degree,” said Kim.

Like Kim, other journalists have attempted undercover journalism in North Korea. Some like Euna Lee and Laura Ling spent time in brutal North Korean prisons for their reporting. Other journalists who made it home were limited to what the regime allowed them to see. Vice News conducted an undercover operation using the Harlem Globetrotters as a guise. In 2016, National Geographic’s Lisa Ling conducted a similar visit when she went undercover for 10 days accompanied by a visiting doctor. Although revealing, these well-orchestrated trips hovering with minders—secret police assigned to all visitors—are an attempt by the government to present a wealthy and healthy nation. North Korea does everything to combat its image with presentational activities of lavish banquets and entertainment to faux computer labs with open, non-working google homepages.

“To write about it with any meaning, or to understand the place beyond the regime’s propaganda, the only option was total immersion,” Kim said.

The Grand Mass Artistic Performance Arirang, 2 month festival by Roman Harak

Suki Kim found her way in by applying to be an English teacher at a private school built, run, and paid for by Evangelical Christians who agreed to hide their religious beliefs from students and citizens. A 2016 report from Christian Solidarity Worldwide explains the country makes these deals as a “survival strategy to seek goods and support from, and improve their image.” For six months Kim was pretending to be an English teacher who is pretending not to be a Christian missionary.

While there Kim was under constant surveillance. “The school was a heavily guarded prison posing as a campus,” Kim said. Every teacher was assigned a minder, every room in the school was bugged, all of her lesson plans were pre-approved by the regime, and every day a different student was selected to secretly write a report on Kim for the government. Kim and the other teachers were only allowed to leave campus on government-sanctioned outings to national monuments with minders. To report on her life there, Kim had to smuggle USBs into the country, which she then kept under her clothing day-and-night. She used them to save her findings after deleting her work from her computer.

But it is the everyday lives of Kim’s students, the young male citizens aged 19 to 20, that is the most shocking. They are never allowed contact with their families, they can never leave school, and are never permitted to be alone. They are paired up with a student companion who writes reports on their partner’s daily activities. Kim said, every moment of their lives is dedicated to either schoolwork or worshipping their “Great Leader.”

“I went there looking for truth. But where do you even start when an entire Nation’s ideology, my students day-to-day realities, and even my own position at the university, were all built on lies?” Kim said.

She initially struggled to gauge her students true opinions. She thought essay writing might be revealing, but that didn’t work as critical thinking is essentially prohibited. So, she came up with a weekly “personal letter” for her students to write. Of course, these letters would never be allowed to be sent to their loved ones, but it began to reveal her students’ real feelings. “They wrote they were fed up with the sameness of everything. They were worried about their future,” Kim said.

Kim and her students spent every meal and nearly every moment together. She began to care deeply for the young men, or her “gentlemen” as she fondly called them. From there she began to struggle with a personal battle; should she tell them the truth?

“But for them the truth was dangerous,” Kim said. “By encouraging them to run after it, I was putting them at risk of persecution, of heartbreak.” She knew enlightening them in any way might cause them danger. Kim would rather they forgot her than allow their interactions to change them.

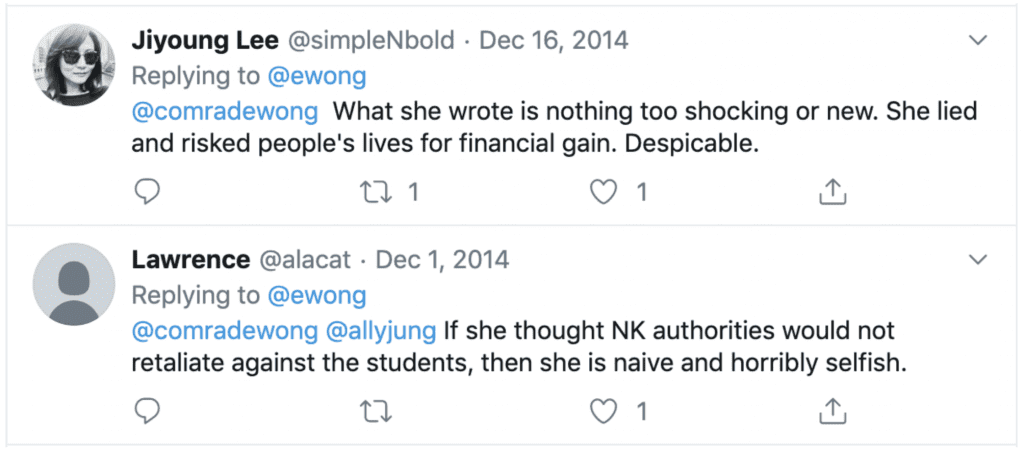

After publishing, the backlash to Kim’s reporting was swift. The New York Times published a story on the blowback from Pyongyang University. “They have denounced Ms. Kim for breaking a promise not to write anything about her experiences and said her memoir contains inaccuracies,” it read. After the article was published, comments and Twitter posts questioned her ethics and even the truth behind what she wrote.

Pyongyang University also fought back with videos of seemingly free students, a lively Facebook page, and alternate reports from visiting teachers. Although Kim changed her students’ names and presented them as loyal to the regime, others still persisted in questioning the danger she might have put her students in.

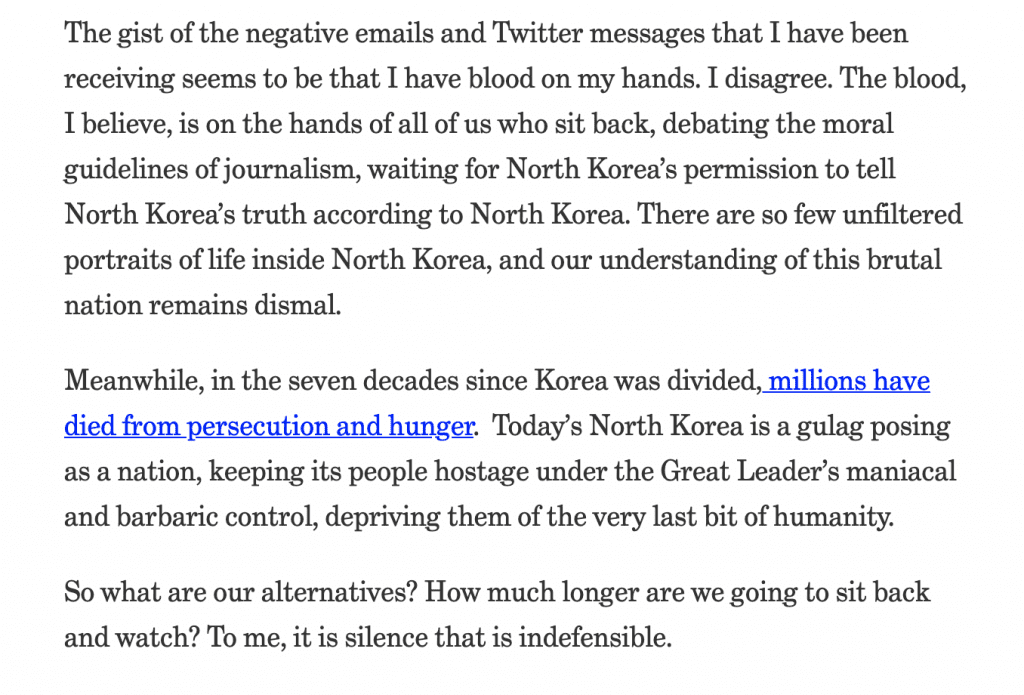

Kim then responded to the article and claims with a statement on her website.

Excerpt from Suki’s Kim’s “ethics note”

The only way Kim could get to the truth was to go undercover and mislead the regime as to her intentions. She made the brave and important choice to give voice to the voiceless, and she did so while protecting the people that mattered, the students.

“I found whatever the world outside wanted to believe, that it wasn’t as bad as it might be in North Korea—it’s actually worse,” she said,