A mass student walkout that shuttered New York University’s student-run newspaper made national headlines in September. But amid the noise and accusations that led to the unprecedented protest, the most revealing glimpses at this saga’s complexities came from the corrections those stories were eventually forced to publish.

Reporters from national publications like The New York Times and Jezebel covered the September walkout at Washington Square News, in which more than 40 staff members resigned after publishing on the paper’s website allegations against their new editorial adviser, Dr. Kenna Griffin.

Those accusations included charges that Griffin belittled the entire staff, disrespected WSN’s Black staff members, and that she exhibited unnecessarily harsh and rude behavior.

A CHALLENGING STORY

The New York Times covered the event on Sept. 28. That piece focused on an issue raised in the students’ resignation letter: a controversy around the use of the word “murder” to describe the death of Breonna Taylor, a Black woman killed by police in Kentucky back in March.

A WSN editor told the Times “that Dr. Griffin had failed to explain the journalistic use of the word in a Slack message to staff.”

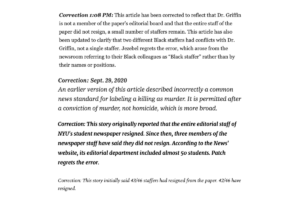

The confusion over that word choice extended beyond WSN. The day after publishing the piece, the Times issued this correction:

An earlier version of this article described incorrectly a common news standard for labeling a killing as murder. It is permitted after a conviction of murder, not homicide, which is more broad.

Other outlets soon followed with their own coverage of the events — and their own corrections. The Click reached out to the writers of the stories mentioned in this piece, but most declined to comment or did not respond to messages. Except one.

“When you’re on a deadline covering a buzzy story, it can be hard to understand who is competing for what, and I think that’s the central issue for all of those corrections,” Siri Chilukuri, a contributing writer at news blog The Objective, told The Click.

Chilukuri published her own story for The Objective on Oct. 1.

That piece followed the same line of coverage as other outlets (including the struggle over the use of “murder” in the Breonna Taylor case), and it featured interviews from new sources. Like the Times, though, Chilukuri had to add a correction to her story after it went up: “This story initially said 43/46 staffers had resigned from the paper. 42/46 have resigned.”

At least four news outlets issued corrections to their reporting on the Washington Square News staff walkout. [Credit: India Edwards]

A similar correction ran on an article published by Patch, a news platform covering local communities. The piece was published on the hub covering New York City’s West Village. In bold, italicized fonts above the article, it reads:

This story originally reported that the entire editorial staff of NYU’s student newspaper resigned. Since then, three members of the newspaper staff have said they did not resign. According to the News’ website, its editorial department included almost 50 students. Patch regrets the error.

Both corrections highlighted the challenge reporters faced in determining how many people resigned from the publication, and who they were — and just how tangled the facts in the story had become.

“Publishing something wrong is a journalist’s worst nightmare, and rightly so,” freelance writer Cristiana Bidei wrote in a 2019 post about corrections for the International Journalists’ Network.

“Still, to err is human, especially in fast-paced newsrooms, and issuing appropriate corrections can limit damages.”

Bidei wrote that mistakes can appear in different ways, “including typos, misquotes, misleading wording, defamatory statements, omissions or wrong facts.”

As any journalist can attest, errors are more likely to happen in stories with sources who don’t cooperate, or when reporters are rushing to meet a deadline.

FIGURING OUT THE FACTS

One of the biggest points of confusion in the WSN saga has been Griffin’s position at the paper.

Previous investigations by The Click have yet to prove whether or not Griffin is employed by the university, how she was hired, or who brought her on in the first place.

Jezebel ran into the same problem when its writer covered the story on Oct. 1. A lengthy correction on that story currently reads:

This article has been corrected to reflect that Dr. Griffin is not a member of the paper’s editorial board and that the entire staff of the paper did not resign, a small number of staffers remain. This article has also been updated to clarify that two different Black staffers had conflicts with Dr. Griffin, not a single staffer. Jezebel regrets the error, which arose from the newsroom referring to their Black colleagues as “Black staffer” rather than by their names or positions.

Jezebel’s correction also highlighted the issue reporters have faced dealing with the racial aspect of this story.

“Everyone had different viewpoints and I wanted to solidify in the reader’s mind that this isn’t like a ‘cancel culture’ story,” Chilukuri said. “This is a story of multiple people wanting to do the best journalism possible in their minds and the harm that comes from their competing visions.”

Although reporters might think of corrections to their stories as a form of defeat, they can also reveal how difficult it is to report on certain topics, and the research and investigation required to unravel complex events.

For Chilukuri, mapping out the people involved in a story can help unravel its intricateness.

“Literally draw a map,” Chilukuri told The Click. “[Draw a map] of the different groups of people and the central issue and then the different people who fall within one group. It helps you not only to see who is in what group but what tension exists within a group.”