Tricia and Joshua Fleishman, shown above, are the second and third-generation owners of Fleishman Fabrics on historic Fabric Row. This photo was taken in the current store at their current location on the row. [Credit: Bobby Brier]

(PHILADELPHIA) — For a brief time this fall, the old streetcar tracks were visible again on South Fourth Street in the historic Fabric Row section of the city. Before the street was repaved in November, the dull shine of the worn steel provided a window to the past for a historic business corridor well versed in adapting to the demands and challenges of American life.

Today is no different in many ways, as some of the remaining fabric, design and clothing stores on the row adapt to the persistent challenges of COVID-19.

As of this writing, Philadelphia has 79,646 COVID-19 cases including 2,127 deaths.

Despite these numbers, business owners on the row have found a way to adapt during the pandemic, similar to the newly arrived immigrants a century ago who were looking for opportunities on South 4th Street.

Jewish Immigrants on South 4th Street

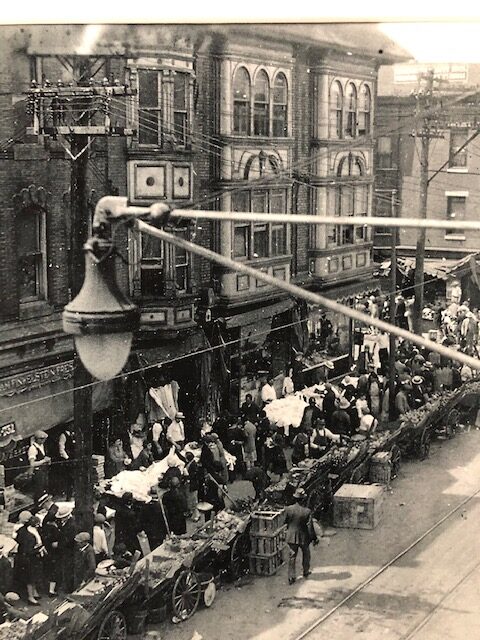

This photo shows South 4th Street in 1927, according to a storefront window display at Maxie’s Daughter. The “twin” buildings on the right-hand side of the photo became the location of Louis Winitsky’s store, Michelle Winitsky Palmer’s father. Palmer added that this photo shows the building long before her father owned it. [Credit: Michele Winitsky Palmer]

Jewish immigrants from Europe arrived on South 4th Street in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and patched together a livelihood as tailors, seamstresses, and salespeople with pushcarts that lined South 4th Street. The street became known as “Der Ferder”, which in Yiddish means “the fourth.”

“[M]y dad came over from Russia in 1923 just before the United States pretty much closed off immigration from that area,” Michele Winitsky Palmer said during a recent phone interview. Palmer wrote The Fabric of Our Lives: A History of Philadelphia’s South Fourth Street for The Museum of Family History, a virtual museum that tells the stories and history of Jewish families.

“[H]e and his family just snuck in under the wire, so to speak, and actually his father was a tailor and he had come over 13 years earlier, so that would have been in 1910. [He] (Palmer’s grandfather) wanted to bring the family over, but meanwhile there was so much going on. There was World War I and pogroms and the Russian Revolution and the Russian Civil War. [So] much stuff that they were actually lucky to get out 13 years later.” Pogroms were genocides carried out against the Jewish community in Russia and Eastern Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Joel Spivak, a Philadelphia historian and author, echoed the narratives of survival and change for Jewish immigrants to South Philadelphia. “[W]hen people came over, that area—the Fourth Street [and] South Street area—was called the Jewish Quarter, pretty much taking the entire Fabric Row which basically was Fourth Street from Lombard Street, which is one block north of South Street, all the way down to Washington Avenue.”

He added, “[T]here used to be a place on Bainbridge Street that was a Jewish center. So, people came on the boat, if you came from Europe, Russia, wherever you came from, and you came to Philadelphia, they had a immigration landing at Washington Avenue and Delaware Avenue. [W]hen you got up to 3rd and Bainbridge, there was a thing called the Talmud Torah and they helped you find your family who were in the United States. [T]hey helped you adjust to the ways of America and then there were benevolent societies that helped you open a business.”

For families like Palmer’s, who lived above the fabric store when she was born, these businesses were the lifeline to making a living in a new city. When the Great Depression hit in the late 1920s and throughout the 1930s, Fabric Row shops prospered, according to Palmer, because people could not afford to buy their own clothes or drapes. Instead, people had to make their own and used materials from Fabric Row shops. World War II, meanwhile, was a different story.

Louis Winitsky, right, and one of his business partners, Phil Morgenstern, left, showing new fabrics. Palmer estimates that this photo was taken in the late 1950s or early 1960s. [Credit: Michele Winitsky Palmer]

Today on Fabric Row

Fleishman’s Fabrics was also in business around Fabric Row in the late 1920s and early 1930s. The 95-year-old fabric store is one of only seven fabric stores that remain today on the historic street. According to Palmer and her research into the Spring 1950 city directory, there were around 25 fabric stores on Fourth Street in 1950. “There might have been more or less at other times but 1950 was still part of the post-war boom heyday,” she said via email.

The Fleishmans have survived through the years by changing with the times. Adapting to the demands of COVID-19 was no different, store owner Tricia Fleishman said.

Fleishman Fabrics remained open in the early months of the pandemic by providing the materials to make masks, including interfacings and elastics. Since then, some of their revenue has come from customers seeking to purchase fabrics and other decorative material to make costumes and dresses to commemorate smaller events.

“[W]e have been very lucky to be in the kind of masking-making boom industry that is sewing and fashion,” said Joshua Fleishman, a third-generation store owner and Tricia’s son.

Monica Monique Thompson, owner of Oxymoron Fashion House and MONICA MONIQUE Fashion House, displays clothing in her store on October 24th, 2020. Thompson opened her store in September 2015 and focuses on creating and designing high-end bridal gowns and prom dresses. [Credit: Bobby Brier]

Originally starting just off of Fabric Row at 5th and Monroe Streets, Fleishman’s was once in the drying cleaning and tailoring businesses. They also sold wholesale fabrics, dry cleaning supplies and tailoring supplies and still do today.

“[I]f you knew about us, we were the best kept secret because you would come around the corner [to 5th and Monroe] and probably get things for much less than they were selling on retail Fabric Row,” Tricia Fleishman said.

Fleishman Fabrics decided to leave 5th and Monroe in part “to fill a void,” according to Tricia Fleishman, because the number of fabric stores on Fabric Row continued to dwindle.

“[T]he thing about these stores is unless you have perpetuity in a family business like these, it’s not going to continue. [M]ostly they started [as] mom-and-pops many, many years ago, and unless it continues in the family, it’s not something that has legs to keep going. [W]e were very fortunate to have Josh who came and tried it out and stayed. [T]hat gave us the impetus to just continue and grow it in different ways that reflect a more modern version of what we used to be,” she said.

“[T]hose kind of fabric stores that remain, I like to tell people who knew about historic Fabric Row, they’ve also diversified, including us. So, there’s things that we carry now that are either trendy in fashion or that we never had in five years ago, 10 years ago. Everything from spandexes to sequins to glitters to rhinestone fabrics and trims. [T]here’s less fabric stores, but those that are here have expanded to carry more to represent more of the industry,” Joshua Fleishman added.

Other small business owners on the row have also adapted and diversified to meet the current challenges of the pandemic, including the utilization of online sales.

Monica Monique Thompson, a 30-year-old small business owner of Oxymoron Fashion House and MONICA MONIQUE Fashion House who specializes in making high-end prom dresses and bridal gowns, adapted to the demands of the pandemic by making her own masks. Between the months of March and June, these were her best-selling items. Thompson donated masks to nurses, doctors and anyone walking down the street who did not have a face mask. Her 2020 sales stand in stark contrast to her sales from previous years because March through July is usually the time when she makes 60 percent of her yearly income on prom dresses and bridal gowns. 2020 changed that, but Thompson knows that she can adapt.

“I feel like I’m always going to survive because I’m a fan of the pivot,” she said. “[I]f the world catches on fire tomorrow, I’m just going to start making fire suits.”

COVID-19 has affected Thompson’s business because she has seen a growth in her online sales since the pandemic began. This has also been a reality for Elena Brennan, the owner of Bus Stop Shoe Boutique, a high-end women’s shoe store on Fabric Row.

Elena Brennan, owner of Bus Stop Shoe Boutique, stands in her store on Fabric Row next to a pair of red shoes she designed. Her designer brand is Bus Stop X. [Credit: Bobby Brier]

As the pandemic continues into the winter with no sign of a widespread vaccine available to the general public until 2021, established fabric store owners and small business owners on the row will have to push forward and continue being creative in their business approaches to make a living with the tools they have at their disposal, just like the families that came before them.

“[W]e were literally working from 7 am to 10 pm,” Tricia Fleishman said of trying to survive the beginning of the pandemic. “[Y]ou have to have the wherewithal to say you’re going to keep going and keep your head down. You can’t give up. I probably haven’t worked that hard in 40 years. [I]t’s possible, but you have to think outside the box and we did that and fortunately we’re still going.”