A Brooklyn Dodgers sign welcomes visitors to the complex. Photo courtesy of Ruth Stanbridge, President of the Indian River County Historical Society

Tucked away in a small seaside town on the east coast of Florida stands a historic jewel. Known as Dodgertown, this sports complex once sparkled under the tangerine sun. For 60 years, America’s favorite pastime forged an unlikely relationship linking the tiny town of Vero Beach and the glamorous celebrity-filled spotlight of the Brooklyn and later the Los Angeles Dodgers baseball team.

“It was so special,” said Jim Stoeckel who worked for the team from 1981-1999. “We knew it couldn’t last forever.”

In 2008, everything changed. The team left and Dodgertown closed. Since then, the complex has witnessed many transformations; it has decreased in size, changed names, and switched directions multiple times. “Every degree of separation, it becomes harder and harder to maintain that connection and link to the past,” said Stoeckel.

While its past is what made it special, the struggle over its remaining relevance, if any, looms over this historic facility. Beyond the patinaed memory of legends who used to play here, what purpose do these hallowed grounds have? In 2019, Major League Baseball came up with an answer while trying to solve a much larger issue.

A League of Their Own No More

Much has been made about the decline in popularity of the sport. Other major hurdles for MLB include a decrease in young African-American talent as well as a changed landscape for young players entering the game.

In 2015, MLB player Andrew McCutchen wrote, “Baseball used to be the sport where all you needed was a stick and a ball. It used to be a way out for poor kids. Now it’s a sport that increasingly freezes out kids whose parents don’t have the income to finance the travel baseball circuit.”

According to USA Today, the average cost of travel baseball is around $3,700 a year. That price can easily accelerate upwards if a family opts for additional training or if a team travels for out-of-state tournaments.

“The sport of baseball has an extreme divide between those who can afford the private and specialized hitting and pitching coaches and those who can’t,” observed Vero Beach resident and former FAMU college baseball player Kendrick Willis. That cost difference has dropped the engagement of disadvantaged youth from the sport.

So what is it about Dodgertown’s unique past that could help solve MLB’s modern dilemma? The answer dates back to 1948.

Aerial shot of Holman Stadium, circa early 1950’s. Photo courtesy of Ruth Stanbridge, President/County Historian of the Indian River Historical Society

The Golden Days of Dodger Blue

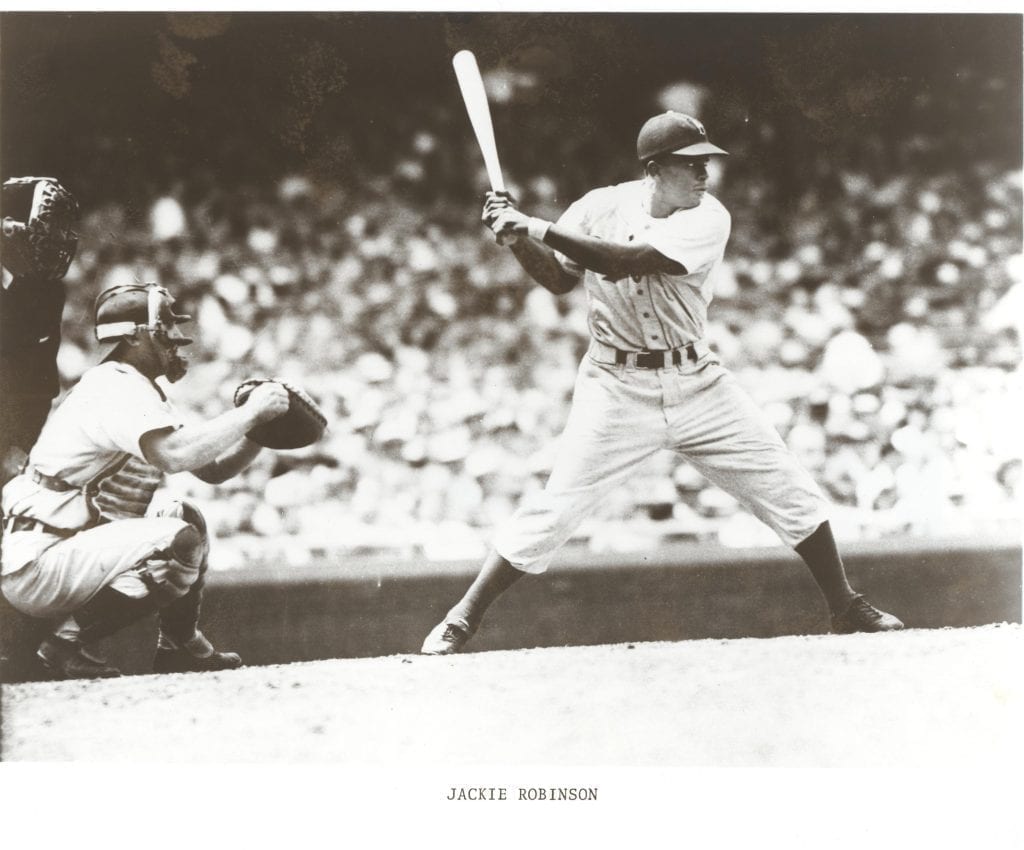

Built as a spring training facility, Dodgertown was originally erected for one purpose – a singular spot where every Dodgers baseball player, regardless of race, could live, practice, and eat together. At the time, segregation was still deeply embedded within society. Jim Crow laws in the South enforced a “separate but equal” way of life. This was a predicament for Brooklyn Dodgers team president Branch Rickey and his newest star, Jackie Robinson.

Robinson became the first African-American to be signed by a major league baseball team since 1884. Rickey, determined to tap into the Negro league and recruit better talent, needed a complex where the team could break the color barrier and train together. Built on the land of a former U.S. Naval Air Station, Dodgertown became the first racially integrated spring training camp. The location proved to be so significant that, in 2014, Historic Dodgertown was named a Florida Heritage Landmark for the role it played in the civil rights movement. In early 2019, Historic Dodgertown became the only sports property on the U.S. Civil Rights Trail.

Dodgertown was also a symbol. “After the war, the team was here. The Dodgers gave us a sense of place,” said President of the Indian River County Historical Society Ruth Stanbridge. For the local African-American community, Robinson provided something more. “It gave us a little hope. We were inspired by the fact that hopefully things were getting better,” said Dr. A. Ronald Hudson in a video for the Indian River County Historical Society.

Jackie Robinson, No. 42, at the plate for the Brooklyn Dodgers in Holman Stadium. Photo provided by Ruth Stanbridge, President of the Indian River County Historical Society

After six World Series Titles and 14 National League pennants, many factors pressured the team to move west to Arizona. The fierce east coast roots that tied the team and the town together started to dissolve. Fans, who had stuck with the organization even after it left Brooklyn for Los Angeles in 1958, were aging. In the mid-90’s, percolating right under the surface, there was a heavy possibility the team would one day leave. “The economics of the game ramped up. Vero was the smallest town in America to have a minor league club,” said Stoeckel.

On March 17, 2008, the team played its last spring training game in Vero Beach. Dodgertown closed that December.

Build It … But Will They Come Back?

For a few years, Minor League Baseball tried to run a multi-sport complex but grew frustrated and wanted out. Peter O’Malley, the former Dodgers president and owner, stepped in.

Craig Callan, Vice President of Historic Dodgertown, recalled, “With such a strong affection for Vero, he (O’Malley) said let me run it.” O’Malley, along with his sister Terry and former Dodger pitcher’s Chan Ho Park and Hideo Nomo, got the deal done. The complex found new footing.

In December 2018 county commissioners approved a deal in which MLB agreed to pay the county $1 per year and invest millions of dollars towards renovations. In January 2019, MLB took over and that spring renamed the facility the Jackie Robinson Training Complex.

MLB’s incentive to keep these grounds in operation is two-fold. Locally, it has become a way to make money. Jeff Biddle, Vice President of JRTC, came to Vero in 2009. He helped transform it into a multi-sport complex. “The advantage now, is this is a year-round business. In 2018, we had 13,000 participants and coaches. That generated 33,000 room nights for the community.”

Aerial shot of present day Jackie Robinson Training Complex. Tournaments for youth baseball, men’s baseball, and women’s softball are held here. The 100-by-130 yard field can accommodate football, lacrosse, and soccer teams. Photo courtesy of Jeff Biddle

The second reason links back to MLB’s goal to “diversify and strengthen the talent pipelines of baseball and softball”.

For the past three decades, MLB has fallen behind in the development of young talent within the African-American community. According to The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport, or TIDES, the number of African-American players in baseball has declined over the last few decades. In 1991 the percentage of African-American players in the league was 18%. On Opening Day in 2018, African-Americans made up only 8.4% of team rosters. (That is the highest percentage over the last six seasons.) Compare these numbers to other leagues and the discrepancy is huge. In the NFL, African-Americans make up 70% of the roster. The NBA is even higher at 74.4%.

“For a lot of kids, if you don’t have the means, there is a whole demographic left out,” said Biddle. “There aren’t that many opportunities for young players to be introduced to baseball in an affordable way.”

In 2015, MLB and the MLB Players Association worked together and committed $30 million dollars to fund a new initiative. With the help of current and former players, programs throughout the country were established to bring the game to young kids. Vero now serves as the home base for many of those initiatives.

As the facility rebrands and works to replace old signs, this historic stone Dodgertown sign will remain on the property. Photo by Tiffany Corr

The Game Changer

The Hank Aaron Invitational is held at the complex. 250 amateurs from across the country are trained by current and former MLB players and coaches. All at no cost to the participants. “It’s incredible,” said Biddle. “They talk with these kids and tell them, whether it’s on the field, in the front office, or in broadcasting, there is a place for you here in baseball.”

The Breakthrough Series invited approximately 60 high school players for a weekend development experience at JRTC this past June.

Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities, or RBI, has grown to more than 200 cities and approximately 2 million participants. In August, the JRTC hosted the RBI World Series and made Vero its permanent host.

Robinson would have turned 100 years old this year. Dodgertown is 71. In a day and age when the past is quickly forgotten for the newest ‘it’ thing, the jewel of Vero Beach is proof that history lives on.