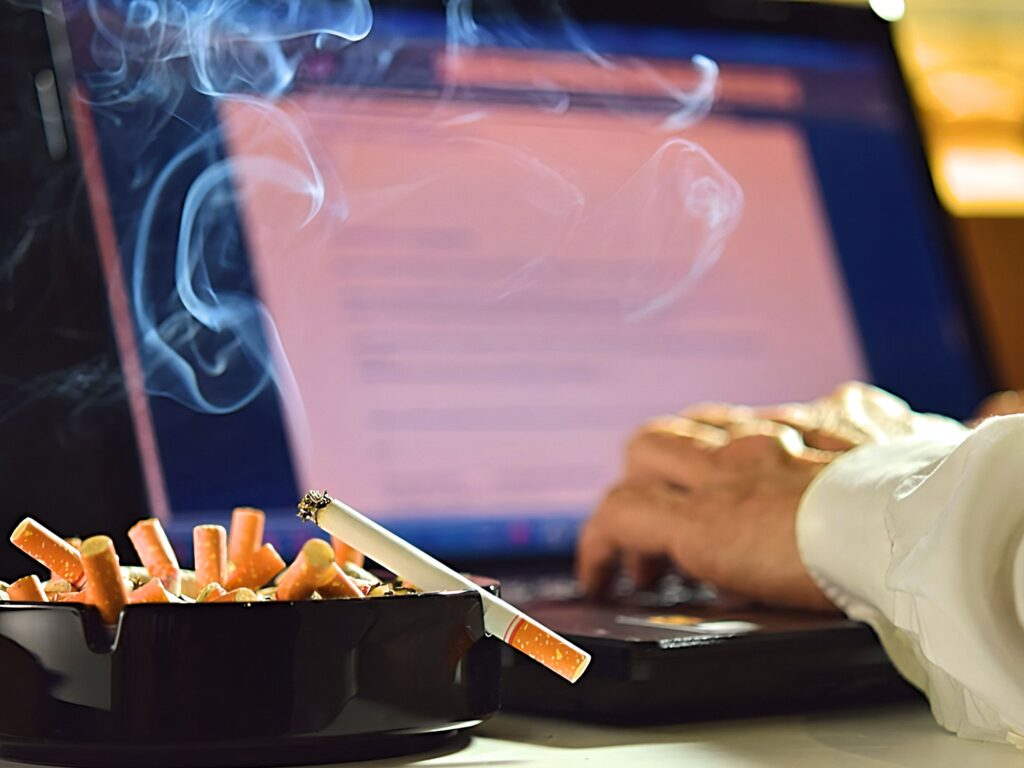

(ATLANTA) – National concerns of journalistic integrity typically revolve around undercover reporting, misinformation, and anonymous sourcing. A less sultry but exceedingly more problematic dilemma is less spoken of, to the benefit of virtually every news outlet. “Churnalism,” a term coined by BBC journalist Waseem Zakir, is the cigarette of the journalism industry: A quick 10-minute hit that tars the lungs long-term.

Churnalism is slang for the process of regurgitating press releases, scientific studies, and other media outlets with nothing, or next to nothing, added. In other words, the final product branded as journalism lacks original analysis and research. Nick Davies, in his 2008 book, “Flat Earth News,” popularized Zakir’s term, though the habit has been around since before either was born.

Though the language to describe churnalism is new, the disease is older than journalism. Before the printing press, propaganda was touted among governments and churches. But once mass publication was possible, power became less about oration, a complete book became less sacred, and the speed at which opinions and facts could spread through pamphlets and newspapers was exponential. As typical, the rich and powerful were able to continue to influence conversations but, more inspiring, advocacy found a new tool.

Benjamin Franklin used the printing press to promote freedom for the colonies, freedom for slaves, and for freedom of journalists. In a 1789 article, he said, “If by the liberty of the press were understood merely the liberty of discussing the propriety of public measures and political opinions, let us have as much of it as you please.” He did foresee issues with the weaponization of the written word. Franklin goes on to worriedly predict more attacks of character from citizens to citizens. “But if it means the liberty of affronting, calumniating, and defaming one another, I, for my part, own myself willing to part with my share of it.” Much more egregious than Franklin’s worry is the institutional abuse of the populace when journalists stop fighting the status quo.

One area often subject to the plight of churnalism is health and science journalism, especially in the United States, where the average media outlet rushes to summarize a “new study” or jargon-filled research without any further investigation.

For example, a recent article by the New York Times (NYT) regurgitated information from a study on medicine for those with Long-Covid. The study itself contains a large disclaimer: “This article is a preprint and has not been peer-reviewed. It reports new medical research that has yet to be evaluated and so should not be used to guide clinical practice.” While the NYT acknowledges this towards the end of the article, they did not analyze the study.

Adam Cifu, MD, points out that the NYT omitted essential details to regurgitate the news. A key fact about the study is that it was still in an observational period, meaning it can make no claims about causation, only correlation. When the headline says the pill “may reduce” risks, it is merely guessing. Curiosity is lacking and not enough skepticism on the journalist’s part is applied concerning who benefits from the results of this research.

I reached out to Dr. Cifu for further comment on how journalists can prevent their articles about scientific research from turning churnalistic. He elaborated, “Don’t go for the easy exciting interpretation that you know deep down is probably wrong.” Adding, “Remember that important discoveries are rare and surprising ones are even rarer.”

Avoiding churnalism does not necessarily mean avoiding studies. One example, from the Wall Street Journal, does a great job of summarizing complex scientific jargon in a rat study about their ability to recognize musical beats without becoming a mouthpiece for the researchers by including skeptical angles. Proper analysis was enacted on rodents’ music taste instead of important information that relates to public health. The subject matter is not what determines the merit of journalism, or the journalist.

Churnalism can be painfully plain. In January, CBS Miami headlined an article, “Gov. DeSantis Awards $80 Million For South Florida Storm Resiliency Projects.” An eerily similar headline to the Florida government press release that came out on the same day: “Governor Ron DeSantis Announces $80 Million in Awards for Community Storm Resiliency Projects, Highlights Florida’s Economic Momentum.” The problem is that CBS Miami did zero auditing. The journalist simply highlighted some of the information available in the press release. Neither article mentioned the important context: Rebuild Florida program is funded federally, which makes the gratitude toward DeSantis generous at best.

“Everyone wants to be first but it’s not possible.” Melissa Lynn Walsh, a recent graduate of political science and journalism at Kennesaw State University, told me that wanting to make sure a story is on a news organization’s website can cause reporters to rush. But it’s not always because of a bad motivator. “I feel like you’ll often retell stories, especially if it’s a news organization who focuses on national stories, but how you tell the story can be different.”

Retelling stories with new elements is indeed a worthy task. Repeating the news is not always nefarious. Sadly, the guiding ethics of a newsroom can prioritize dollars over duties.

Current funding structures for most American news outlets, local and national, go like this: Advertisers need clicks, clicks are coming to news outlets, more clicks attract more advertisers, and news outlets attempt to generate as many clicks as possible. But there is even more money to be made if news organizations simply agree to bear the responsibility of becoming advertisers.

While many, myself included, love The Associated Press and Reuters for their “just the facts” approach to storytelling, it is not because they are unbiased good-hearted truth-seekers. As communications expert and author, Thomas Klikauer points out, “Reuters earns well over 90% of its money from selling news to the global finance industry. As a consequence, Reuters is far more likely to cover the price of cotton than the life of the cotton worker.”

As off-putting as a BuzzFeed “article” headlined, “38 Things You Won’t Believe You’ve Survived This Long Without,” can be, where there is a symbiotic partnership that makes all parties money, the most nauseating form of churnalism is when news publications simply hand the metaphorical typewriter to politicians. Even if there is a caveat thrown at the bottom of the article, the general public perceives such collaboration as an endorsement. Nationally, take the example of Mike Pence not so subtly beginning his presidential campaign through a commissioned op-ed for the Wall Street Journal that pleads his case. Locally, it can look like the Mayor of Atlanta insulating himself from any critique of his housing crisis philosophy. Let them have their social media and press releases, but it is inexcusable to fold the power of the fourth estate to becoming a de facto spokesperson.

Deeper into the churnalism machine, the Bezos-owned Washington Post churned out the article, “Jeff Bezos says he will give away most of his massive fortune,” and many other outlets followed suit without challenging the truthfulness of that promise. Where are the actions that prove his words mean anything?

Independent publishers cannot compete with monopolized establishments. As reputable independents vanish, an even more propaganda-filled world appears. When reporters cower to the financial motivation of more clicks by quickly regurgitating PR with no criticism, they defile their duty and become useless.

Scarier still is the prospect of robots producing nothing but churnalism to the joy of the billionaires behind most mainstream media. The Washington Post, and other media outlets, are hopeful for AI “to enable journalists to do more high-value work.” Clear motives are disguised through PR talk. Churning out articles means more ads, and more ads imply more profits.

A revival of journalists, unafraid of both internal and external institutional pressure, who think newsworthiness should not be determined by the stakeholders of the attention economy, is paramount. This isn’t mere lethargy, it is enabling a numb society.

I asked Philip Seib, Professor Emeritus of Journalism and Public Diplomacy at the University of Southern California, what qualifies as original reporting. In over 20 years of reporting and media criticism, he said. “I tried for originality in the topics I addressed, and rarely followed the lead of another news organization. I liked to be first on at least a particular angle of an issue, but I didn’t worry much about ‘breaking news.’ I primarily wanted the news audience to think and care about the issue at hand.”

Perhaps that is the solution, since prioritizing breaking news is clearly a broken system. Reacting to a story recently revealed is for social media users; not journalists. An analysis is not a “hot take” or a few lines of context, it’s telling a story; not rehashing a blurb.

Early 20th-century author Aldous Huxley, in his 1931 dystopian classic, “Brave New World,” wrote, “Wordless conditioning is crude and wholesale; cannot bring home the finer distinctions, cannot inculcate the more complex courses of behavior. For that, there must be words, but words without reason.” It is tempting to assume that “fake news,” disinformation bots, and bad actors are the biggest threat to a society that values truth. Hypnotically, unchallenged words are as grim.

The temptation to generate stories quickly allows the rich to get richer and poor story writing, as well as poor people, to become poorer. Churnalism might feel relaxing in the fast-paced world of journalism, as is smoking a pack of cancer sticks. But journalists need to quit it; cold turkey.