(LOS ANGELES, C.A.) — Kinokuniya is the only bookstore that sits in Downtown Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo within a plaza across the street from the community’s only library. At both locations, visitors can connect with Japanese traditions through a huge selection of literature and entertainment.

This cultural preservation is important for Yoko Hata, who discovered the Little Tokyo Branch Library (LTBL) while grocery shopping shortly after immigrating to Los Angeles in the 1990s from Japan.

“As a book lover, I went to the Little Tokyo Library almost every day from the day I found it. As I went, I became acquainted with the library staff and we began to greet each other [in Japanese] and engage in conversation,” said Hata, one of the children’s librarians for LTBL.

The library and bookstore opened their doors in the 1970s and have supplied the public with books in English and Japanese. Japanese culture thrived more at their businesses despite Japanese people making up only 2% of the community’s total population.

Kinokuniya’s inventory connects the neighborhood to manga, graphic novels that originate in Japan, and other Japanese texts. Similarly, LTBL welcomes the community with free, Japanese-themed workshops. Most notably, the library holds bi-monthly “Japanese Storytime” where books are read out loud to children in Japanese.

Population Demographics

The population peaked in the early 1900s when approximately 10,000 Japanese people resided throughout Los Angeles and many settled in Little Tokyo. As of 2020, Little Tokyo housed over 37,000 residents with Asian people making up 36% of the population followed by Latinx, white, and Black residents, according to the U.S. Census.

Although Asians account for the largest racial category, Chinese is the dominant ethnic group and makes up half of Little Tokyo’s Asian population. But the population of Chinese immigrants was not always so vast.

Decades before the U.S. bombed Pearl Harbor and sparked World War II, the government passed the Chinese Exclusive Act of 1881 that prohibited Chinese immigrants from entering the country. The law was enacted after American workers complained about having their jobs taken away by Chinese immigrants who were blamed for poor wages and other economic struggles.

The law was in effect until 1943 when the U.S. was in the midst of the war and were in need of resources in Asia to defend themselves against Japan. At that point, the U.S. government repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act and gained China as an ally.

Additionally, Koreans comprised 5.5% of the community, Vietnamese were at 3%, Filipinos totaled 2.8%, and Japanese were just 2% of all residents in 2020.

To continue the legacy of the original Japanese immigrants such as Hamanosuke Shigeta – a former sailor, who opened one of the first Japanese restaurants in Little Tokyo in 1885 – the LTBL hosts events that encourage Japanese literacy, with toddlers as their target audience.

Hata and library volunteers lead the LTBL “Japanese Storytime.” Together, the group holds sessions filled with classic nursery rhymes, short books, and age-appropriate activities.

On a Saturday morning in early November, eight children and seven parents sat on a blue rectangular rug printed with numbers and multi-colored bullseyes. Padded seats lined the walls and smiling plush caterpillars laid on top of bookshelves.

A cheery “Konichiwa! Ohayō goziamasu!” – which means “Hello! Good morning!” in English – signaled the start of story time. Hata’s crew sang the numbers from one to 10, read a book about brushing teeth, belted out other children’s songs such as “Head, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes,” and played a guess-the-animal game.

Meanwhile toddlers rolled around, babbled along, and danced as older children raised their hands and participated.

After 35 minutes, the presentation was over. Hata handed out a take-home kit to attendees that included a paper lion face cut out and autumn-toned leaves to be glued as its mane.

Although this day’s turnout was smaller than expected in comparison to October’s event that hosted 11 kids and 21 parents, their loyal attendees were there. Hata says that the most consistent family first attended in May 2013 when the mother had a toddler and was pregnant with her second child. Now, the older child is 10-years-old and the younger sibling is 8-years-old.

“Thanks to Storytime [my children] are interested in both English and Japanese books…They get to interpret stories through [two languages] and expand their imagination,” said Hiroko Turner, the mother of those two children. She says that she’ll continue to attend Storytime with her children because of the linguistic and creativity benefits.

Turner’s children fall into one of the neighborhood’s smallest age categories. Children between the ages of five and 17 make up only 5% of Little Tokyo’s total population, according to the 2020 American Consumer Survey.

LTBL’s young adult librarian Robert Lippman, understands the frustration of engaging with a small, target audience. He said the library’s teen section does not receive much foot track.

“There aren’t a lot of kids living here. Kids come here as a destination. They come to the market across the street. They’ll come to the bookstore [Kinokuniya] and the places that sell manga stuff and go get food or ice cream,” said Lippman.

Since March, Lippman has implemented different outreach strategies. He curated a book list with LGBTQI+ themes for LGBT Pride Month in June, posted and handed out fliers with QR codes for the library’s manga collection, and organized a field trip with a local high school.

Librarian Robert Lippman leading a presentation. (Photo courtesy of Robert Lippman)

Ultimately, Lippman has one goal: “We want to get the books in the hands of people who want to read them.”

Bookstore Bliss

LTBL and the bookstore often work together. Hata regularly orders books from Kinokuniya’s manager, Kenji Iizuka, when patrons request them. Kinokuniya’s selection includes English and Japanese translations of children’s stories, textbooks, cookbooks, and manga.

“The customer’s happiness is my happiness,” Iizuka said.

When he started, the store was where only people who speak Japanese and Otaku – fanatics of anime, manga, and video games – would shop. He believes with the increased availability of Japanese content on streaming websites, the market will continue to expand.

In recent years, the shop’s customers are from different racial backgrounds and have open discussions about the merchandise and their favorite books. Iizuka sees the diversity in customers’ interests in Japanese literature as opportunities for personal and social growth.

“[Customers are] learning the spectrum of emotions such as friendship, grit, perseverance, and sadness through manga by putting their perspective on the main character’s point of view. [It makes them] more open-minded, and expand[s their] view of life. Without having a barrier of race, manga is able to spread, as even non-Japanese people are able to learn and understand these feelings and perspectives,” Iizuka said.

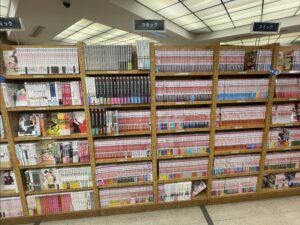

Manga collections at Kinokuniya. (Photo courtesy of Jessica Montes)

For others, Japanese literature has a deeper significance and connects them with extended family. Mackenzie Smith, 19, was on her first visit to the bookstore and browsed the aisles with friends.

Smith, who is Black, shared that one of her relatives married into a Japanese family, and for the past five years, she has taken Japanese language classes to connect with her in-laws. While she can only hold simple conversations, she feels the real learning starts when you engage with others.

“Japanese is such an interesting culture and studying it [by yourself] doesn’t do it justice. You need to get out there and talk to people,” Smith said.

Hata has first-hand experience of how a shared language can bring people together. Like the librarians she encountered during her first visits, Hata welcomes patrons who primarily speak Japanese and find comfort in conversing in their native tongue. She hopes her work helps the community embrace its linguistic origins and history.

“I feel like I can’t speak English that much but when we are [at LTBL] we can communicate in Japanese…Parents come here and enjoy conversation with us and I can talk with the kids and we are really close,” she said.