(SAN FRANCISCO) —Before San Francisco will let anyone build within its 49 square miles, it puts them through a set of tribulations worthy of Greek myth. The Fifth Church of Christ, Scientist, a century-old church in the Tenderloin, is one such contender.

The church leadership has been trying to rebuild their colonnaded structure for a third of its lifetime. Last year, they thought they had finally grabbed the ring. They had been through five years of environmental review, a negotiated truce with the preservation society, and two approved designs. They proposed a 13-story tower with residential units and a new church.

In September 2021, they sat before the 11 mandarins of City Hall who get the final say — the San Francisco supervisors. Hours of public comment were heard. Ultimately, every single one of these mandarins raised thumbs turned downward.

Since the tech boom of the 2000s, San Francisco has become one of the three most expensive housing markets in the country topping the list for income needed to afford a home. With housing production not keeping pace with the influx of new residents, the city’s affordability crisis has gotten worse. It has been hemorrhaging essential workers as they get priced into the exurbs.

The rebuilt church would have brought 316 modern units targeted precisely to that demographic: middle-income essential workers. It would have done so in a neighborhood — the Tenderloin — that is crying out for rejuvenation. Why, then, did the supervisors unanimously turn it down?

The Tenderloin, a neighborhood of contrasts

View of Tenderloin at Shannon St. Mural by Amos Lee Gregory [Credit: Suraiya Brister]

It is 50 square blocks of downtown, surrounded by theaters, retail, and transit. If not for concerted political pressure from residents, it would have been gentrified into a jungle of condo towers decades ago.

Instead, the TL, as locals know it, is dense with Single Residency Occupancy units (SROs), group housing with tiny, city-subsidized studios with communal bathrooms and kitchens. These are often the last tier before homelessness. Many were built more than a century ago, soon after the 1906 earthquake razed the city, and are now in a state of disrepair. Many are designated as historical buildings, reminiscent of the milieu of Dashiel Hammett’s novels.

Little of that bygone romantic era remains. Today, of the Tenderloin’s 27,000 or so residents, about a third live in poverty, almost half are first-generation immigrants, and almost a quarter do not have basic English competence. Home ownership is almost non-existent, and more than three-quarters of the residents live in single-person households.

The TL also has high levels of homelessness and street crime. Often ignored by the city’s civil services, it is the epicenter of San Francisco’s fentanyl crisis. When critics of the city reference used syringes littering sidewalks, they are probably talking about the TL. Drug dealers crowd around street corners with users sprawled around them.

Amos Lee Gregory keeping the sidewalk clean [Credit: Aneela Mirchandani]

While the city often falls short, the TL community has stepped up. Volunteers escort children to and from school amidst the addicts. Volunteers paint murals, clean sidewalks, and advocate for tenants. It is this community that the developers of the church at 450 O’Farrell ran afoul of.

A bait-and-switch?

At the City Hall hearing on Sept. 28, 2021, it came down to the size of units. The builder, Forge Development, had planned a 316-unit tower of “micro” units, 300-800 square feet each. The studios would be furnished with kitchenettes, with three larger community kitchens for shared use. They were marketed as innovative “scaled” units for families.

The tenant-advocacy group Tenderloin Housing Clinic (THC) cried foul. An earlier plan for the church had proposed family housing; they saw the change to SRO-type studios as a bait-and-switch. The THC’s appeal to block the development was filed before the planning commission approval was a month old.

Pacific Bay Inn on O’Farrell Street [Credit: Suraiya Brister]

“The neighborhood is crowded with SROs,” said Belinda Dobbs, TL resident. “It would be very nice to have families and children around, it would feel more normal.”

“There are families of four or five living in cramped conditions and need more space to live in,” said Kathy Vaughn, TL resident.

Richard Hannum, the founding partner of Forge Development, rejected the unit size critique. “By square footage the building is the same building as before,” he said.

San Francisco is unique in how much local discretion it gives neighbors in approving projects. Perhaps, then, it was inevitable that the representatives of these neighbors would echo their concerns. At the next hearing on Oct. 5, Matt Haney, then supervisor of the Tenderloin district, said, “the units are tiny and lack full kitchens.” Subsequently, all supervisors voted it down.

Sonja Trauss, founder of the pro-development group Yes In My Backyard (YIMBY), thinks the 11-0 decision was unfortunate. “If we have to have family housing in the Tenderloin, fine. But we also have to have group housing in other parts of the city,” she said. “We need efficiency units for singles in San Francisco. The existing SRO units are really old. I’ve seen reports of older people getting trapped in their homes in places that don’t have elevators.”

The YIMBY group believes that the rejection of 450 O’Farrell violates California’s housing accountability law. They have now filed a lawsuit against the city that they hope will set a precedent.

‘Containment zone’ vs. vibrant neighborhood

It is no accident that the Tenderloin has remained a home for low-income residents in a city of sky-high rents. It is the result of fierce advocacy forged in protest against the wave of urban renewal that swept across American cities in the 1970s.

As part of this wave, many SROs were torn down, being seen as blight. Activists in the Tenderloin and other neighborhoods fought desperately to avoid displacement. At first, they failed. In 1977, some 3,000 protesters faced police brutality as they formed a human barricade against eviction before the demolition of the International Hotel.

But then they had some successes.

Randy Shaw, co-founder of the THC, helped pass the city’s Hotel Conversion Ordinance in 1981 (signed by then mayor Dianne Feinstein, herself a hotel owner) that blocked SROs from being converted into tourist hotels. Another legendary mayor, Ed Lee, started his career as an activist allied with THC in the battle to preserve SROs in the neighboring Chinatown district.

Pratibha Tekkey directs an SRO collaborative under the umbrella of THC. “We restricted building beyond 10 floors,” she said. “That killed it for a lot of developers.”

David Elliott Lewis runs a grassroots group called the Tenderloin People’s Congress. “Many of the buildings were given landmark status that protects them,” he said.

Organizers resist the charge that they are anti-development. “We do want development, but not at the expense of displacing long-term residents,” Lewis said.

These habits of political advocacy have carried through to this day. A land use committee, composed of tenant representatives and community organizers, meets regularly to evaluate each proposed development.

Tekkey says the city thinks of the TL as a “containment zone” for drugs and crime. But the reality, she said, is that the TL is a place of families and seniors, who seek public safety and habitability. The city often falls short of providing these basics.

“We are tired of not being able to do what other people get to do,” tenant peer counselor Kathy Vaughn said. “Walking dogs, buying groceries without being harassed by drug dealers.”

“We liked the idea that families would be living there,” Tekkey said. “Granted it would be market rate, but there would be some affordable housing mingled in. It would have brought vibrancy to the neighborhood.”

The vision of vibrancy this community espouses matches the sort of urban life YIMBY activists say they want: diverse, desegregated. A mix of private businesses and supportive housing, a mix of income levels, singles, families, and everything in between.

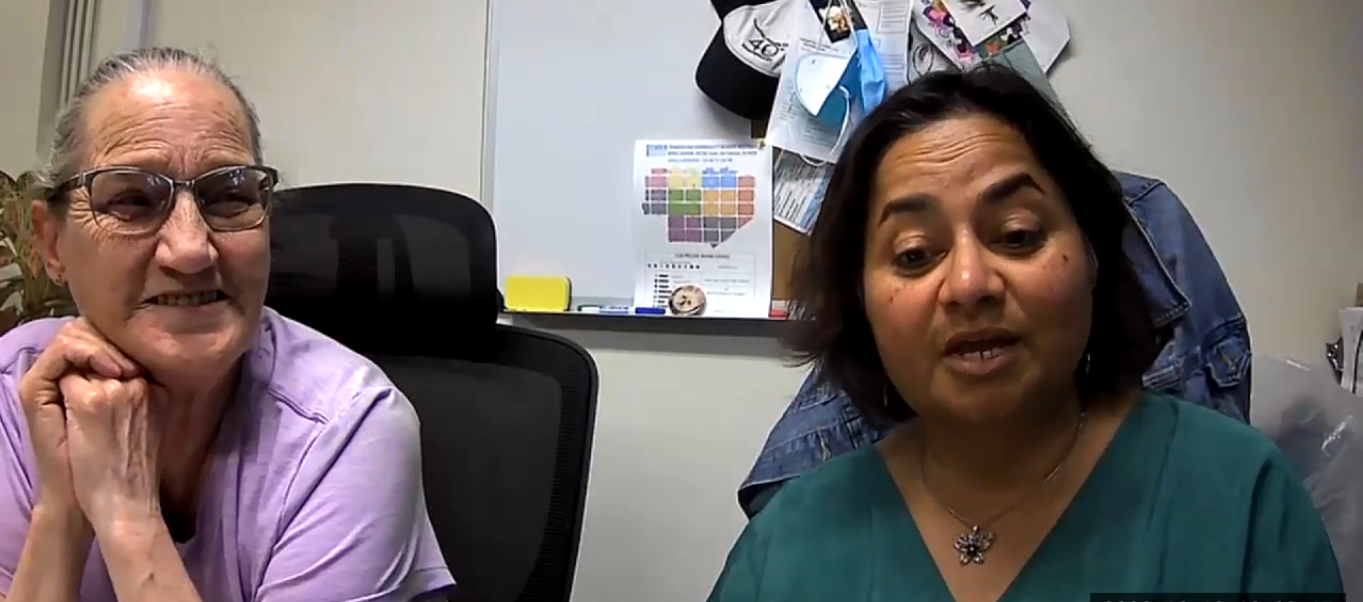

Kathy Vaughn (L) and Pratibha Tekkey (R) discuss the project. [Credit: Aneela Mirchandani]

A constituency forged in protest

In pursuing their project, Forge Development seems not to have understood the political landscape they were dealing with.

Tekkey contrasted Forge’s approach with that of Thompson Dorfman, the developer that had proposed a prior plan consisting of family housing. “They came to our land use committee and gave us presentations. We had a lot of back-and-forth about the design, about community benefits,” she said of Thompson Dorfman.

Forge Development did not respond to a request for comment. However, on its website they reject the notion that no community outreach was done, pointing to “four community meetings, 75+ stakeholder briefings, mailers and area canvassing.”

“They were arrogant and self-righteous,” Lewis said of Forge. “There was a step-up program to house people in regular apartments, with rents paid by a voucher; it wouldn’t even have cost them anything. Instead of meeting us, they sent out PR people to assuage community concerns.”

After multiple calls and emails to the developer went unreturned, Tekkey said, TL activists lobbied each city supervisor to reject the plan. “There was a lot of pressure put on the supervisors,” Lewis says candidly, “I was part of the pressure campaign.”

It worked.

The fallout

In the end, the tragedy remains. A large, centrally-located space, that every stakeholder agrees should be redeveloped, remains unusable though the city is crying out for housing.

The city supervisors chose to address the problem of 450 O’Farrell by clarifying the “muddy and confusing” definition of group housing, as supervisor Aaron Peskin called it. According to this view, inclusion of a kitchenette is what allows developers to play fast-and-loose, by taking advantage of group housing density rules while marketing to families. Peskin’s bill to downzone group housing passed in March.

However, pro-development activists think disallowing amenities is the wrong approach.

YIMBY activist Yonathan Randolph grew up in the city. “Almost my entire life, I lived in illegal inlaw units,” he said. “My grandmother would say, if you ever see a city inspector coming by, don’t show them the stove.”

Because old SRO units do not have kitchenettes, long-time residents like his mother are forced to use hotplates to cook. Randolph believes that it makes no sense to disallow amenities for people who would like to step up from such old units, but cannot afford a condo. He thinks the city should have a range of housing for a range of incomes.

The hearing in Sept. 2021 went over three hours, and all sides got to argue their piece. All sides, that is, except for one: the community that might have formed in the rebuilt church.

Only one person spoke for those missing 600: Del Seymour, a Vietnam vet, former TL resident, once homeless and now a philanthropist who is often dubbed “Mayor of the Tenderloin.” He was one of the few community members who spoke in favor of the project. “I support housing,” he said. “I support unconventional housing, creative housing, unique housing. There’s 600 people who would say, I don’t care about the architecture of it, it would have given me a place to live, and that’s the most important part.”

Murals by Amos Lee Gregory in Shannon St. next to the church [Credit: Aneela Mirchandani]